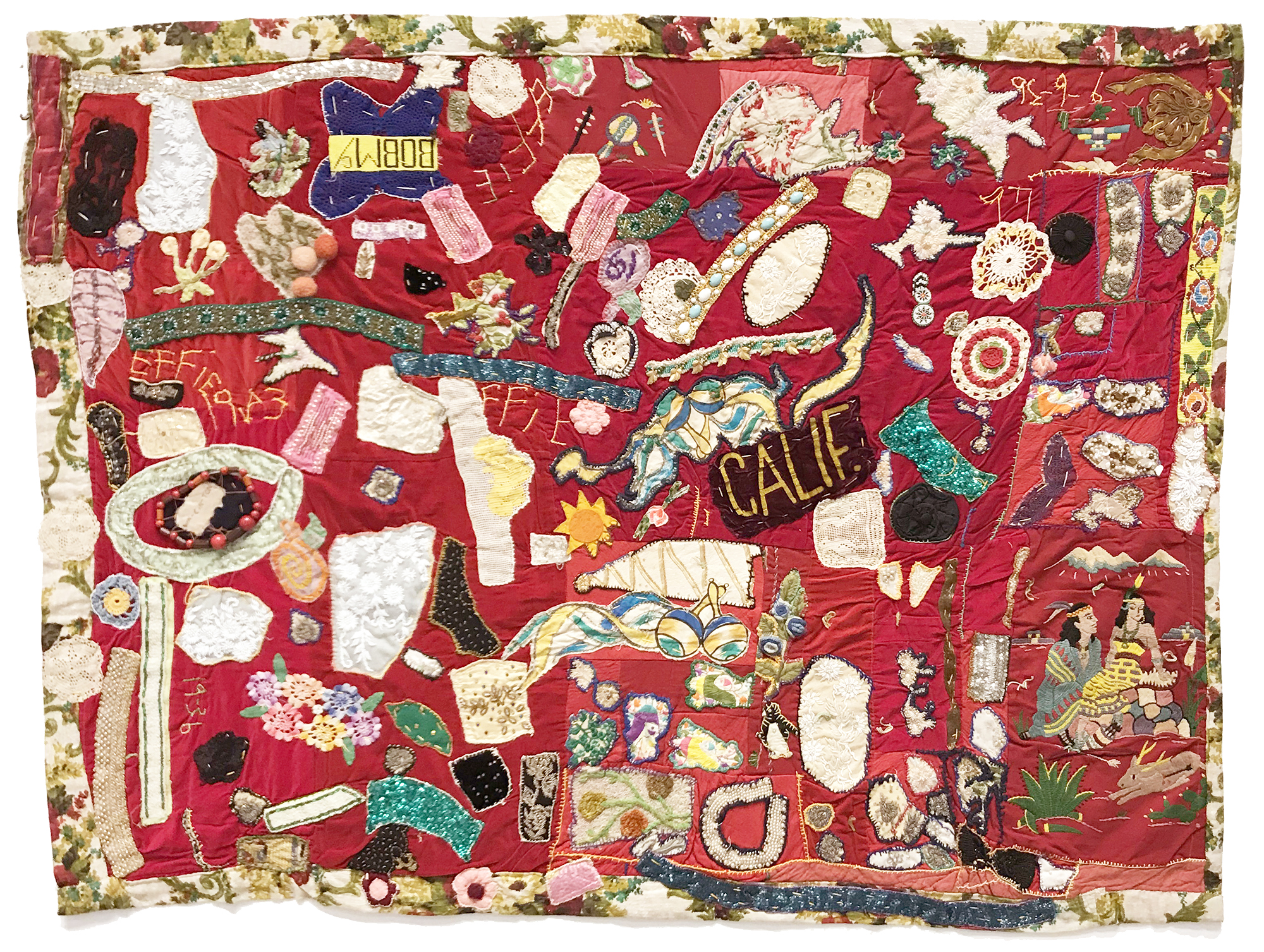

Rosie Lee Tompkins

Rosie Lee Tompkins was a Bay Area quilter known for her brightly colored improvisational quilts. Her abstract narratives included biblical and topical themes and conjure the symbolic codes of Basquiat. Her neo-expressionist forms mix ultra-saturated color with varied textures like fur and velvet.

Tompkins brought traditional quilting into a contemporary art context both in form and in production. Her work was funded by Oakland psychologist Eli Leon, who she met while selling household wares at a flea market. The meeting led to a long and productive relationship between the artist and benefactor, and enabled her to outsource finishing work, bringing the hand and sometimes creative agency of other quilters into many of her quilts.

Paulina Berczynski interview with former BAMPFA Director and Chief Curator Lawrence Rinder

PZB: Do you have any thoughts on how Eli Leon’s patronage affected Rosie Tompkins’ output in terms of encouragement, but also through financial support... so she could focus on the creative act?

LR: He certainly encouraged her, he told her he thought she was brilliant, he encouraged her to exhibit her work, he put her work in exhibitions… so he clearly had a fairly significant impact on her public exposure. He also helped her… on occasion to acquire some fabrics… she was very specific about the fabrics she wanted and she would go out and buy them usually at thrift stores.

And he did hire other local quilters to quilt her pieced tops. She wasn’t particularly interested in quilting, per se. Although there are some examples, like in the show at BAMPFA right now, works where she did the quilting and in those works the quilting, in some cases more than others, does have some kind of sort of visual impact on what you see.

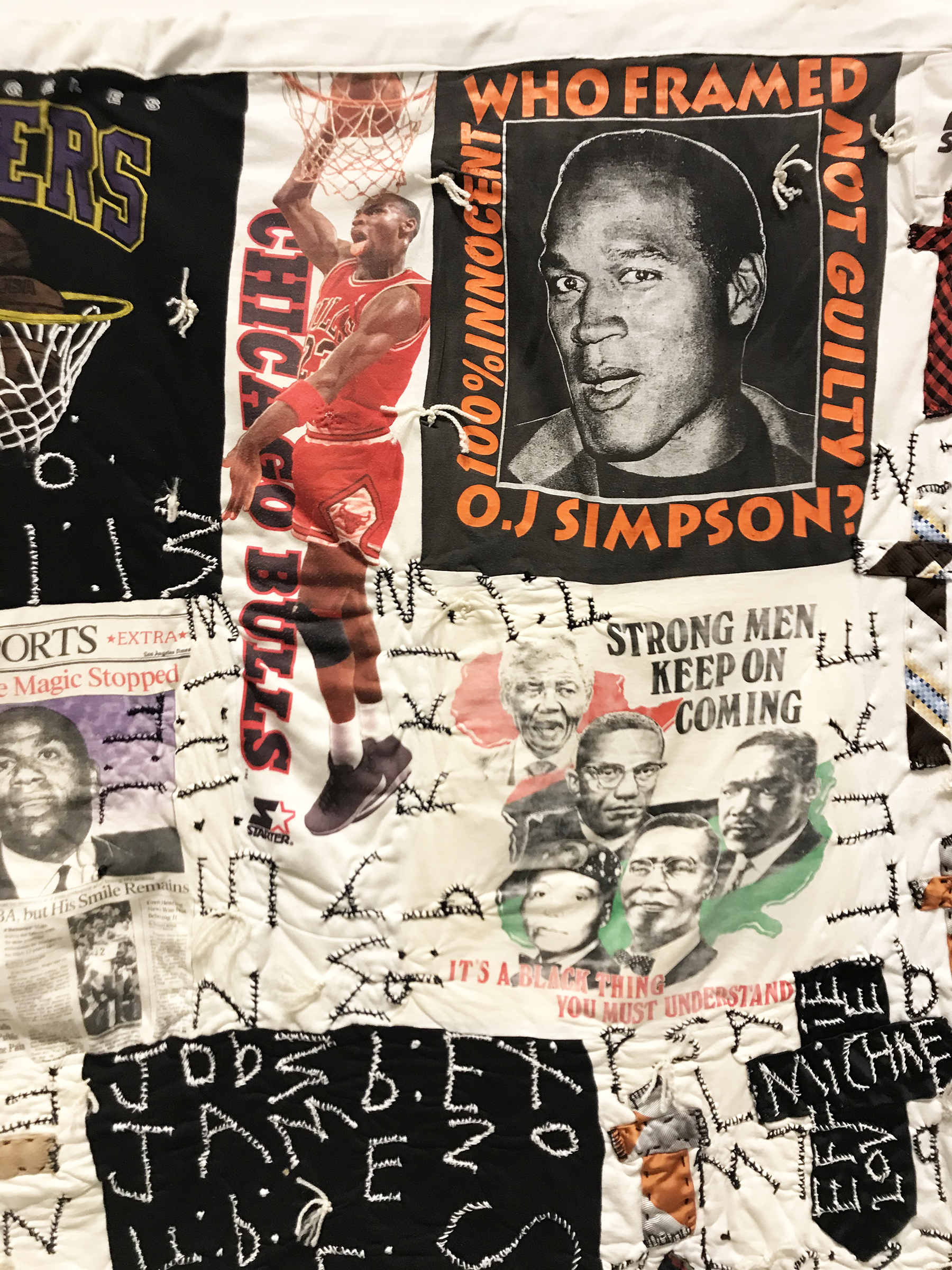

Example of thread-tying in Tompkins work, Berkeley Art Museum

All photographs from Berkeley Art Museum’s retrospective of Rosie Lee Tompkins 2020

In one case in particular its because she uses this method of quilting called tying where instead of using a needle and thread you use lengths of yarn that are drawn through from the back to the front and it creates kind of little puffs on the top that are very visible; and she used yellow string so in that case, she’s emphasizing the quilting as a visual thing. Sometimes she'd add a decorative border when she was doing the quilting herself. But in the vast majority of the works she didn't do the quilting. Eli hired other local quilters to do the quilting and sometimes that had an impact on the look of the piece and sometimes it didn’t, or didn’t have much. I mean there's always going to be some, because if it's with a needle and thread, if you look closely you can see the needle and thread.

This finishing process created a web of support among the artists collaborating on the finished works, financially through job opportunities, but also by offering exposure for those artists as Tompkins’s work gained recognition in the art world. Rinder elaborates on the collaborators, “The people that were doing that quilting were themselves very great artists, Willa Ette Graham, Johnnie Wade and so on... Eli owned works by all of them.” This structure complicates the typical collaborator relationship, in that the artists were being paid in a production format, which mirrors the production houses of well funded artists, but differs in that these artists, well respected in their own practices, are given credit for their authorship.

PZB: I’m interested in the way that these things move between the worlds of craft and fine art. Maybe thousands of women have made similar artworks that are never positioned as art, so it seems Eli Leon was instrumental in changing the perception of her work.

LR: Eli Leon felt that it was great art and so he was concerned that when it was exhibited, that’s how it would be positioned and appreciated. Sometimes someone can come along and start talking about [work] in a different way whether that’s changing the way its perceived from craft to fine art or changing its perception from being impressionist to symbolist. It always takes a person to think in a different way, see in a different way, So yes I think one person can have an influence.

But the question about how did Eli Leon’s patronage affect her creativity? That’s kind of hard to say. I mean the fact that he got people to quilt her pieced tops, I don’t think that necessarily would have freed her up so to speak… because she wasn’t quilting them to begin with. She would just do the pieced top and keep it that way.

There is a small revelation in this last line, and an insight into Tompkins’ creative perspective. If Tompkins sewed the pieced tops and left them unquilted, it would appear that she saw herself as an artist first, using textiles primarily as an artistic medium and some conventions from the quilt’s scale and piecing as tools in her repetoire, skills she learned from her mother. If she saw herself as a quilter first, or a practitioner of the craft of quilting, she would most likely have finished the quilts, and would not have left them as tops.

I had entered into Rosie Lee Tompkins retrospective, and previously into digital reproductions of her work, assuming that she was a quilter first, whose work was discovered and then positioned as fine art by Eli Leon, much in the way that quilts by others such as the Gee’s Bend Community have been “discovered” and positioned as art by people (mostly white men) outside that community. I had assumed her success was what drove her towards more experimental and less quilt-like textile forms in her later work. With this insight into her working process, it becomes clear that Tompkins probably saw herself as an artist all along, and was making contemporary textile artworks, not quilts, when she met Leon.

Do such distinctions need to be made?

In an art world that is keen to show textile art, weaving, and ceramics by male artists at a rate much higher than that of female artists using the same materials - and prone to calling women making similar work not necessarily art, but the more utilitarian and stodgy craft - issues of authorship and intent are relevant, and the positioning of work can be political and nuanced. While Eli Leon was instrumental in bringing Tompkins’ quilts the audience and esteem they so clearly deserve, it is interesting to consider her perspective as an artist, not as a quilter, in making these works.