“I am an artist but that doesn’t mean that I work for free”

“I am an artist but that doesn’t mean that I work for free”Labor Top 10:

A short list on different types of labor in art

by Paulina Berczynski and Amanda Walters

Left: Cover of Czarna Ksiega Polskich Artystow (The Black Book of Polish Artists) featuring a photograph of famous Polish artist Zbigniew Libera holding a sign that reads “I am an artist but that doesn’t mean that I work for free”. The book is the work of the community around the Civic Forum for Contemporary Art, and shows a vision of how contemporary art should be supported and formulated from the perspective of the artists themselves. It also addresses the struggle of Polish artists to improve their status in society, and how this process fits in with the many years of related activity by artists from the EU, Canada and the USA.

The book shows the differences between the popular perception of artists and the creative act and the reality in which artists create. It also describes the relationship between cultural policy and the problems of ordinary art workers - artists and other creators of culture.

1. Tschabalala Self

2. Berber Ruggism

3. Danh Vō

4. Artist Unions, Protests and Strikes

5. Andrea Zittel’s Uniform Project

6. Mary Kelly

7. Claire Fontaine

8. Emotional Labor in the weavings of Christina Forer and Erin M Riley

9. Surabhi Saraf “Fold”

10. Mika Rottenberg

2. Berber Ruggism

3. Danh Vō

4. Artist Unions, Protests and Strikes

5. Andrea Zittel’s Uniform Project

6. Mary Kelly

7. Claire Fontaine

8. Emotional Labor in the weavings of Christina Forer and Erin M Riley

9. Surabhi Saraf “Fold”

10. Mika Rottenberg

1. Tschabalala Self

Above: Installation view Out of Body. Institute of Contemporary Art Boston 2020

Floor Dance. 2016. Linen, fabric, oil pastel, acrylic and Flashe on canvas. 90 x 96 in

In 2018 I saw Tschabalala Self’s textile-based paintings at the New Museum’s exhibition Trigger: Gender as a Toll and a Weapon, curated by Johanna Burton. The works were large. They were so messy they seemed unfinished, with a discomforting aesthetic.… Arresting is a fitting adjective. Stop-you-in-your-tracks arresting.

One work in particular, Floor Dance, evokes the goddess of destruction, or some hyper-exuberant shadow self, in the form of a multi-armed leaping figure in heels. I was transfixed.

I’ve followed her work since, as she focused her inquiry through an exploration of bodega patrons, through the caricatured depictions of the bottom halves of women’s bodies presented on the wall or as sculptures, and throughout, the continued focus on the female form and the every-day lives and figures of black subjects.

Self has been busy. She recently exhibited with Matisse at the Baltimore Museum, among a myriad of exhibitions and honors over the past few years. Her work has ascended to the peak of the art market, with her paintings garnering much attention, and much profit for middlemen and resellers at recent art auctions.

One work in particular, Floor Dance, evokes the goddess of destruction, or some hyper-exuberant shadow self, in the form of a multi-armed leaping figure in heels. I was transfixed.

I’ve followed her work since, as she focused her inquiry through an exploration of bodega patrons, through the caricatured depictions of the bottom halves of women’s bodies presented on the wall or as sculptures, and throughout, the continued focus on the female form and the every-day lives and figures of black subjects.

Self has been busy. She recently exhibited with Matisse at the Baltimore Museum, among a myriad of exhibitions and honors over the past few years. Her work has ascended to the peak of the art market, with her paintings garnering much attention, and much profit for middlemen and resellers at recent art auctions.

After the death of George Floyd, the period of unrest that folowed, a the investment in #blacklivesmatter in many facets of American culture and life, figurative work by African-American women is predictably enjoying previously unheard of attention at auction. These artists and their work are being reduced to their racial and gender signifiers. It’s complicated.

Self has described her relationship to the auctioning of her work, which does not benefit her financially, but represents a financial investment and speculation by wealthy collectors, and profit for the auction houses and resellers.

In an article in Artsy from 2019, Self said “I view the auction as a tasteless spectacle, and I am shocked that the irony of such an event is lost on so many people. As an American descendant of slavery, auctions have a particular historical meaning and politics. I am disheartened that black figures I have produced and fashioned are now sold and traded within a similar context.” pzb

Self has described her relationship to the auctioning of her work, which does not benefit her financially, but represents a financial investment and speculation by wealthy collectors, and profit for the auction houses and resellers.

In an article in Artsy from 2019, Self said “I view the auction as a tasteless spectacle, and I am shocked that the irony of such an event is lost on so many people. As an American descendant of slavery, auctions have a particular historical meaning and politics. I am disheartened that black figures I have produced and fashioned are now sold and traded within a similar context.” pzb

2. Berber Ruggism

Left: Aicha Salmi. 2012-2013

Reaching the height of their ubiquity around 2016, Moroccan rugs, and specifically Berber rugs have gained huge popularity in the Western market over the past decades. These are made by women from the Berber tribal background and ethnicity in North Africa. Over the past decade, chain furniture stores have knocked off the classic Beni Ourain design of black lattice on cream tufted wool, and fantastically colorful Boucherite rag rugs have sold for hundreds and even thousands of dollars. Moroccan rugs are the product of female labor, made in a culture where women were (and often still are) expected by religion and custom to remain in the domestic sphere, rarely leaving home alone. So confined, they have created exuberantly patterned and composed rugs, used as bed coverings, domestic adornments, burial shrouds and animal blankets.

As the popularity of the rugs grew outside of the tribe, they were taken to market and sold by men as tribal heritage markers and cultural products, while the individual makers and creators remained anonymous. The artisan weaver is at the very bottom level of the rug economy in Morocco, with middle men taking most of the final selling price of a rug.

Some weavers never see payment in cash, only in more material to make more rugs. The middlemen control the market. In response to uneducated Western demand for style, suppliers have started producing multiples of popular and traditional designs, using synthetic materials and dyes. Responding to demand of a different sort, for fair labor practices and sustainable consumption, some artisans have formed cooperatives where they have more control over their labor, materials, and profits.

More recently, the myth of anonymity of the makers of the rugs has also started to fall away, and the women creating these highly desirable, beautiful objects, which are a product of their unique creative visions and the motifs passed down through multiple generations of family, have started to gain recognition. Anonymity in this case, as in the case of many hand-crafted artisanal wares, is a fallacy of appropriation and erasure. To see the rugs’ makers revealed exposes, in a particularly human way, the consumerist devouring of individual and culture as global design trends abstract and anonymize labor in the pursuit of profit. pzb

3. Danh Vō

![]()

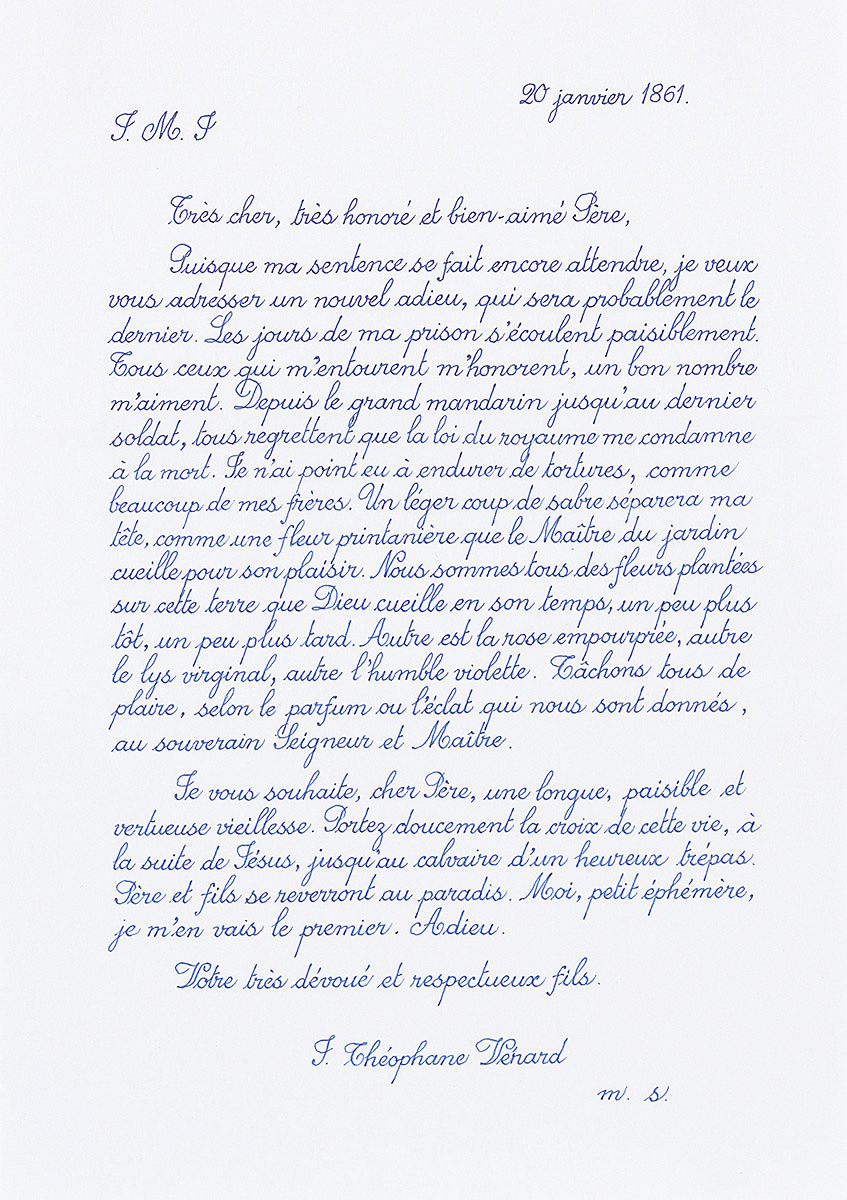

Danh Vō, 2.2.1861, 2009-On the date, 2.2.1861, the French missionary, Jean-Théophane Vénard, was executed by anti-Catholic forces in Vietnam. Vénard penned a letter to his father just before he died. The artwork, 2.2.1861, is one of many replicas of that farewell letter. In an ongoing series, they are penned by Danh Vō’s father, Phung Vō, at the request of his son. Phung Vō is a skilled calligrapher who doesn’t read French. Devoid of the sentiments invested in the letter, the task is reduced to a mere labor between father and son.

The replicas layer the father-son familial relationship, their geographic displacement, and the geopolitical history of the

colonization of Vietnam. AW

The replicas layer the father-son familial relationship, their geographic displacement, and the geopolitical history of the

colonization of Vietnam. AW

4. Artist Unions, Protests and Strikes

As growing numbers of art workers and educators across the US strike and organize for fair wages and labor rights, we think back to a couple of favorite coalitions from America’s art world past.

Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) is a New York-based activist group and non-profit organization whose mission is "to establish sustainable economic relationships between artists and the institutions that contract our labor, and to introduce mechanisms for self-regulation into the art field that collectively bring about a more equitable distribution of its economy." It was founded in 2008 by a group of artists, performers, and independent curators in New York City, including A.K. Burns, K8 Hardy, Lise Soskolne, and A.L. Steiner.

In 2010, W.A.G.E. narrowed its platform to focus on the regulated payment of artist fees by nonprofit arts organizations and museums. They also initiated the 2010 W.A.G.E. Artist Survey to gather data about the payment practices of New York City nonprofits. The purpose of the W.A.G.E. Survey was to gather data about the economic experiences of artists exhibiting in non-profit exhibition spaces in New York City between 2005 and 2010. Launched on September 22, 2010, the survey remained open until May 1, 2011. It collected responses anonymously about forms of payment, compensation or reimbursement received by an artist for their participation in an exhibition, including information about installation expenses, shipping/transportation costs for works, material expenses, and travel expenses, among other things.

The results of the survey, released in 2012, found that 58 percent of the 577 survey respondents who exhibited with small, medium, and large non-profit arts institutions in New York’s five boroughs between 2005 and 2010 did not receive any form of payment, compensation, or reimbursement––including the coverage of any expenses.

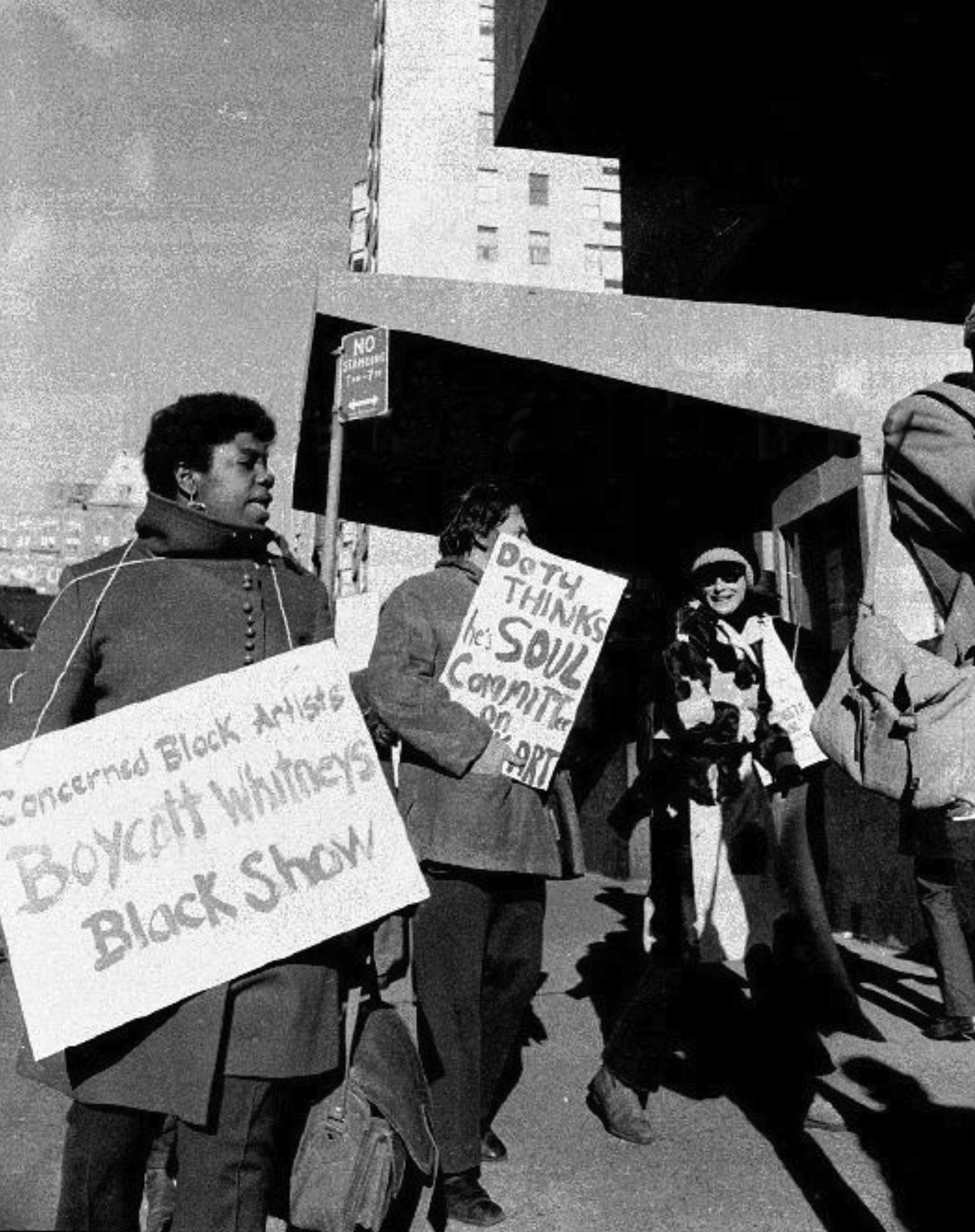

The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) protest documentation

The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) protest documentationThe Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) was organized in 1969 by a group of 75 African-American artists in direct response and protest to the Metropolitan Museum of Art's "Harlem on My Mind" exhibit, which confusingly omitted any contributions from African-American artists

The primary goal of the group was to agitate for change in the major art museums in New York City for greater representation of African American artists and their work in these museums, and that an African American curatorial presence would be established. In 1971, the work of the coalition grew to include the creation of an Arts Exchange program in correctional facilities. This program arose in response to major riots at the Attica correctional facility in New York.

The Art Workers Coalition (AWC) was a collection of artists, dealers, museum workers, and other workers in the art industry. In 1969, the AWC organized a successful "Moratorium of Art to End the War in Vietnam," and called upon all museums in New York to close on May 22, 1970, as part of the protests against the Vietnam War.

Likewise, The 1970 New York Artists’ Strike against Racism, Sexism, Repression and War, also commonly referred to as the Art Strike, was called in the weeks after President Nixon announced he had expanded the Vietnam War into Cambodia. Protesting students had been shot and killed at Kent State and Jackson State universities.

During the Art Strike and in the months before and after, artists argued that trustees exploited their positions on museum boards to distract from their involvement in an oligarchy that perpetrated the Vietnam War. New York museums were asked to instead focus on the needs of more of the city’s residents, to exhibit the work of black, Puerto Rican, and women artists, and to include artists on their boards.

On December 1 1989, the first Day Without Art was instituted as the US art world's national day of action and mourning in response to the AIDS crisis. Implemented by Visual AIDS, an organization of arts professionals founded by arts administrator Thomas Sokolowski, art critic Robert Atkins, and curators Gary Garrels and William Olander, the idea of a day without art was intended to make the public aware that HIV-AIDS can touch everyone, and to inspire positive action. Some 800 U.S. art and HIV-AIDS groups participated in the first Day Without Art, shutting down museums, sending staff to volunteer at AIDS services or sponsoring special exhibitions of work about AIDS.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/a-day-without-art-looking_b_6249150

Here is an excellent, comprehensive PDF on the subject of art strikes in the ArtLeaks Gazette by European curator and writer

Corina L Apostol. pzb

During the Art Strike and in the months before and after, artists argued that trustees exploited their positions on museum boards to distract from their involvement in an oligarchy that perpetrated the Vietnam War. New York museums were asked to instead focus on the needs of more of the city’s residents, to exhibit the work of black, Puerto Rican, and women artists, and to include artists on their boards.

On December 1 1989, the first Day Without Art was instituted as the US art world's national day of action and mourning in response to the AIDS crisis. Implemented by Visual AIDS, an organization of arts professionals founded by arts administrator Thomas Sokolowski, art critic Robert Atkins, and curators Gary Garrels and William Olander, the idea of a day without art was intended to make the public aware that HIV-AIDS can touch everyone, and to inspire positive action. Some 800 U.S. art and HIV-AIDS groups participated in the first Day Without Art, shutting down museums, sending staff to volunteer at AIDS services or sponsoring special exhibitions of work about AIDS.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/a-day-without-art-looking_b_6249150

Here is an excellent, comprehensive PDF on the subject of art strikes in the ArtLeaks Gazette by European curator and writer

Corina L Apostol. pzb

5. Andrea Zittel’s Uniform Project

A-Z Personal Panel Uniform. 1995-1998. Andrea Rosen Gallery.

A-Z Personal Panel Uniform. 1995-1998. Andrea Rosen Gallery.For decades, Joshua Tree-based artist Andrea Zittel’s work has interrogated and re-interpreted all aspects of day to day living, including furniture, food, clothing, and life in relation to landscape, to better understand human nature and the social construction of needs. A-Z Uniforms Project addresses the market demand and social expectation for regular wardrobe changes and the related consumption of new items of clothing.

Zittel proposes that liberation from such demands may be possible through the creation of a set of personal restrictions or limitations. Starting in 1991, Zittel designed and made one “perfect” dress for each season, and then wear that dress every day for six months. During this time she would create the next season’s dress, to be worn for the following six month period, and so on. The project has continued in some form through the present, moving through a variety of materials and fabrication methods along the way. pzb

6. Mary Kelly

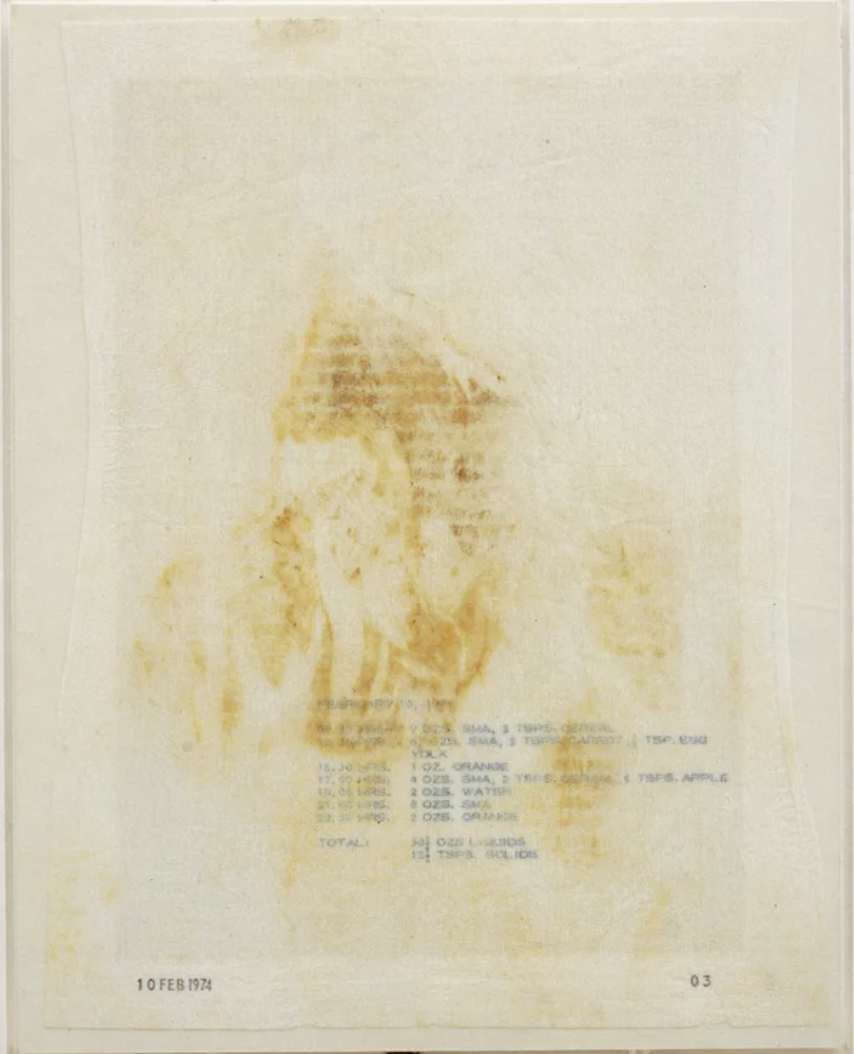

Mary Kelly, detail from Post-Partum Document, 1973–79

Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, 1973-79, perspex units, white card, sugar paper, crayon, 1 of the 13 units, 35.5 x 28 cm each. From Khanacademy.org

Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, 1973-79, perspex units, white card, sugar paper, crayon, 1 of the 13 units, 35.5 x 28 cm each. From Khanacademy.orgFor six years, artist Mary Kelly collected ephemera from her mother-child relationship in the form of notes on her son’s language development, diagrams that quantify her sense of loss, and diapers that demonstrate an unpaid labor, among other didactic documents. aw

7. Claire Fontaine

Claire Fontaine is a parafictional artist from Paris. She was invented in 2004 by real people, Fulvia Carnevale and James Thornhill. Her name was derived from a brand of French stationary. The name is a readymade of a blank page, a theme that extends to her practice focused primarily on the readymade. The form questions systems of object value–the inflation of value offered to an object touched by the hand of the artist–inturn, characterizing the artist as authoritarian. The title, Identité, Souveraineté, Tradition translates to Identity, Sovereignty, Tradition, an inversion of the French principles Liberté, Fraternité, Egalité, or Liberty, Fraternity, Equality. The flags mimic the French flag but vary each stripe, as if charting the variations of those ideals in action. aw

Claire Fontaine

Left: Sans Titre (Identité, Souveraineté, Tradition), 2007 installation, flags, dust, poles, 300 x 200 cm.

Bottom: Untitled, (Identité, Tradition et Souveraineté), 2007. Courtesy Reena Spaulings, New York.

![]()

Claire Fontaine

Left: Sans Titre (Identité, Souveraineté, Tradition), 2007 installation, flags, dust, poles, 300 x 200 cm.

Bottom: Untitled, (Identité, Tradition et Souveraineté), 2007. Courtesy Reena Spaulings, New York.

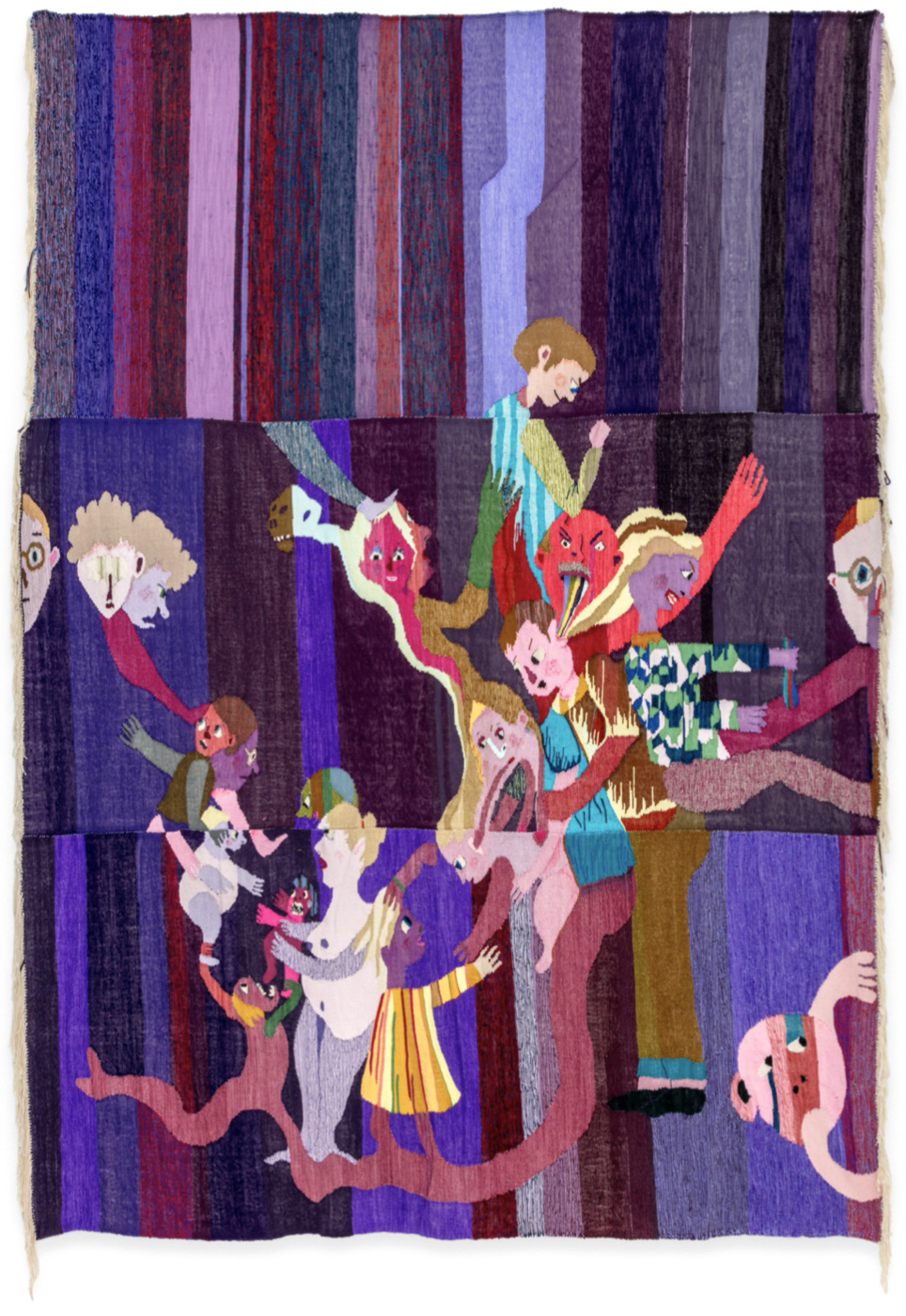

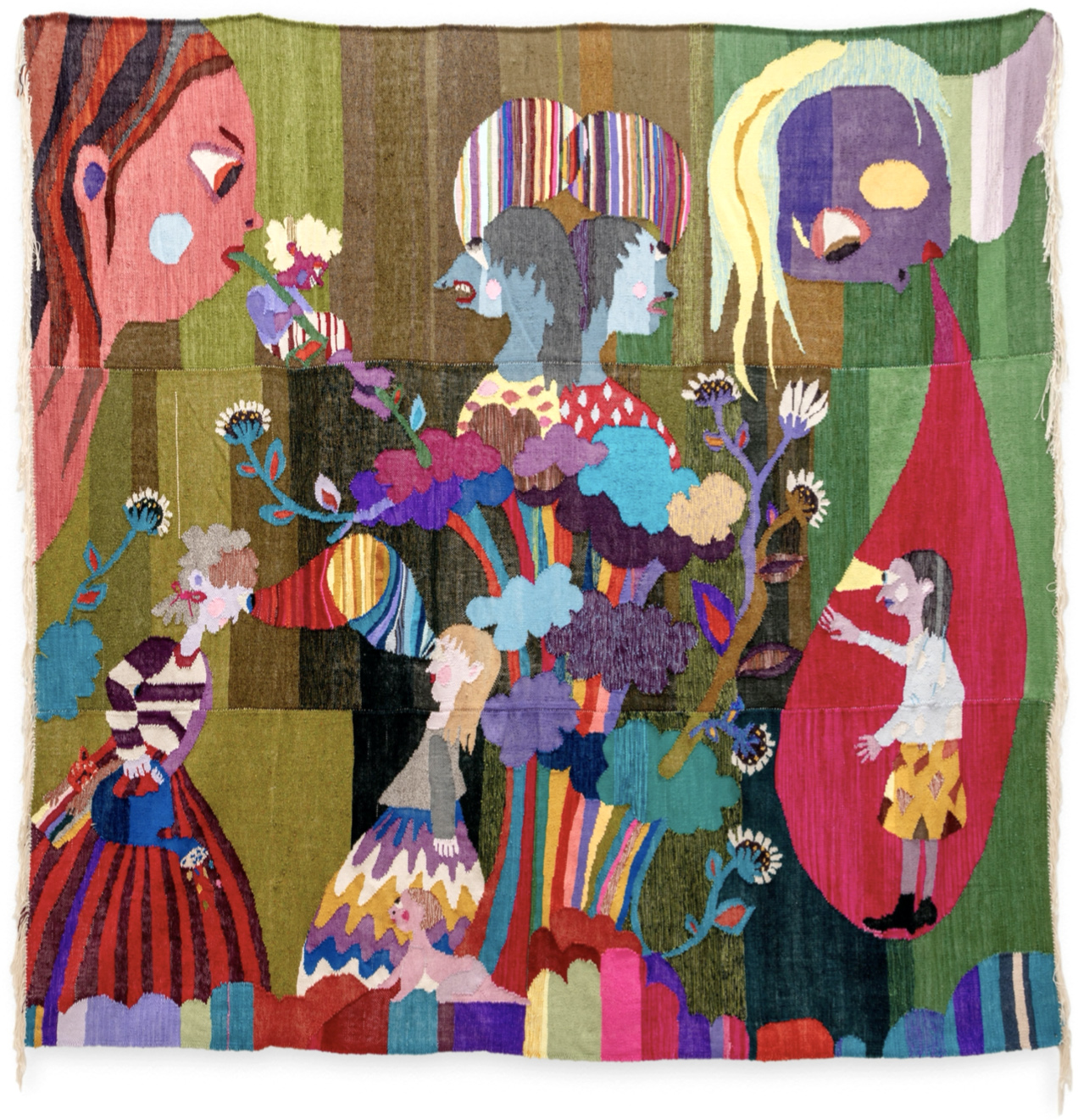

8. Emotional Labor in the weavings of Christina Forer and Erin M Riley

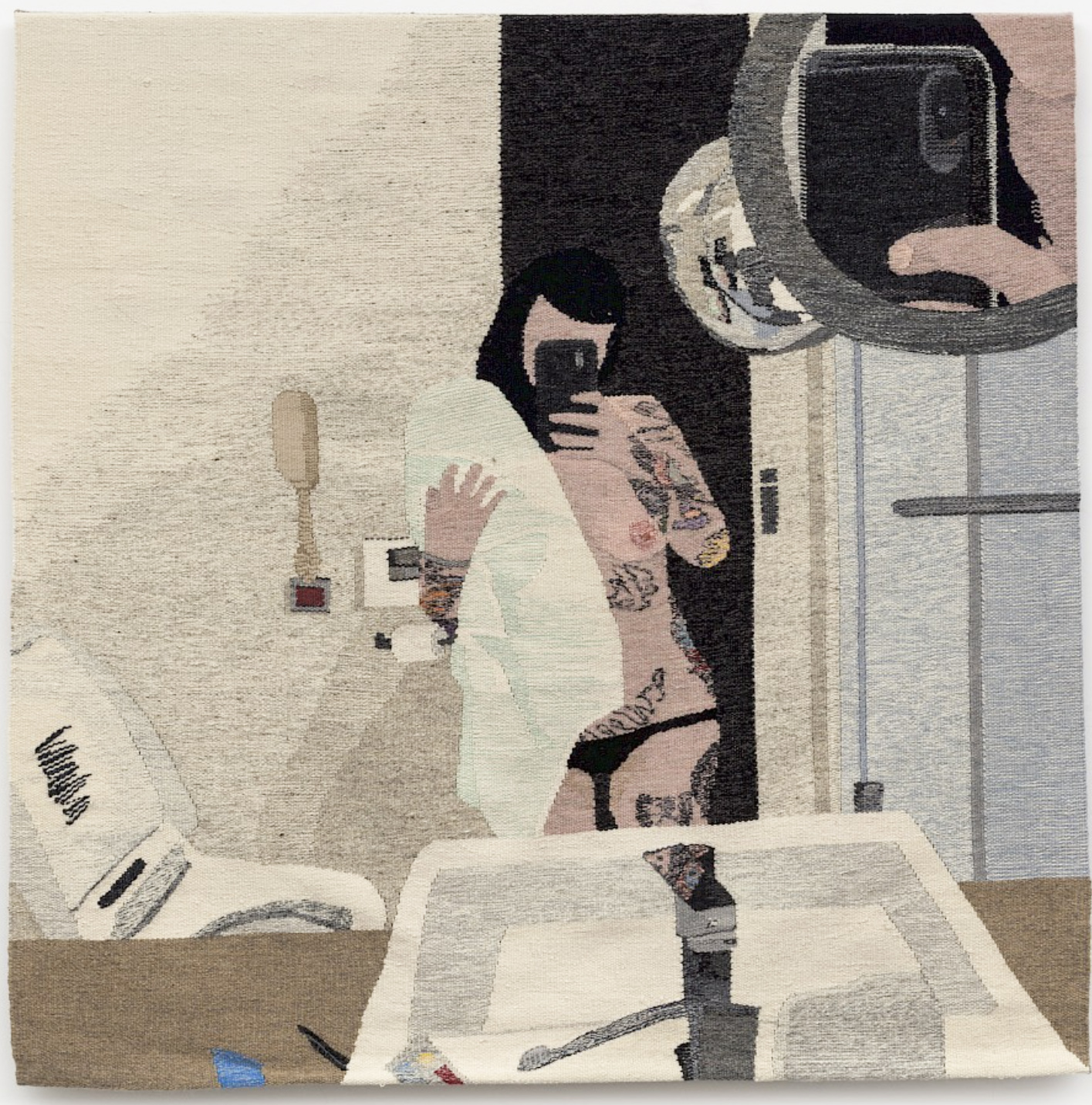

Left: Erin M. Riley. Reflections 4. Wool, cotton. 2019. 48 x 59’

Right: Christina Forrer. Gebunden II. Cotton, wool, silk, linen and watercolor. 2020. 155 x 108”

Right: Christina Forrer. Gebunden II. Cotton, wool, silk, linen and watercolor. 2020. 155 x 108”

Erin M Riley's subject matters are not things you typically see depicted in tapestry. Riley’s weavings have a visceral effect, and implicate the viewer as voyeur. Earlier work in particular presents images of syringes, pornography, and rolls of money amid selfies documenting the dailiness and intimacy of Riley’s relationship with her body and disturbing, private self harm.

![]() Alone in Seoul. Woll, cotton. 2021. 48 x 47”

Alone in Seoul. Woll, cotton. 2021. 48 x 47”

Alone in Seoul. Woll, cotton. 2021. 48 x 47”

Alone in Seoul. Woll, cotton. 2021. 48 x 47”In contrast to Riley’s work, Christina Forrer’s bright tapestries at first present as colorful, whimsical and bright – reflecting the simplified forms and direct visual communication of her native Swiss fables and folk art. On second look, the colorful figures and shapes in her work contrast and complicate the difficult emotions, interpersonal conflict and tension presented within.

I consider these two artists together in thinking on the topic of emotional labor, and what it means to dedicate so much focus to the laborious and time-consuming process of weaving difficult and likely painful subjects.

Their works are also compelling in their relationship to traditional tapestry. Tapestry reached the height of its popularity in the 1300s and is often associated with wealth, patronage, and depictions of elaborate narrative scenes (and the occasional white unicorn).

Riley’s work deviates from these forms by focusing on the personal and the intimate, and the particularities of the artist’s life.

I consider these two artists together in thinking on the topic of emotional labor, and what it means to dedicate so much focus to the laborious and time-consuming process of weaving difficult and likely painful subjects.

Their works are also compelling in their relationship to traditional tapestry. Tapestry reached the height of its popularity in the 1300s and is often associated with wealth, patronage, and depictions of elaborate narrative scenes (and the occasional white unicorn).

Riley’s work deviates from these forms by focusing on the personal and the intimate, and the particularities of the artist’s life.

Intervisions. Wool, cotton, linen and watercolor. 2020. 144 x 113”

Intervisions. Wool, cotton, linen and watercolor. 2020. 144 x 113”Forrer’s work more closely reflects the narrative tools more often associated with the form, however the narrative is opaque, the subject matter rather intangible and emotional, more than depicting any recognizable action or scene. Rather than inviting the viewer in as participant or co-conspirator, both Riley and Forrer’s weavings confront their audience with a remote vulnerability. pzb

https://www.artforum.com/video/christina-forrer-on-battles-in-tapestry-59409

https://erinmriley.com/home.html

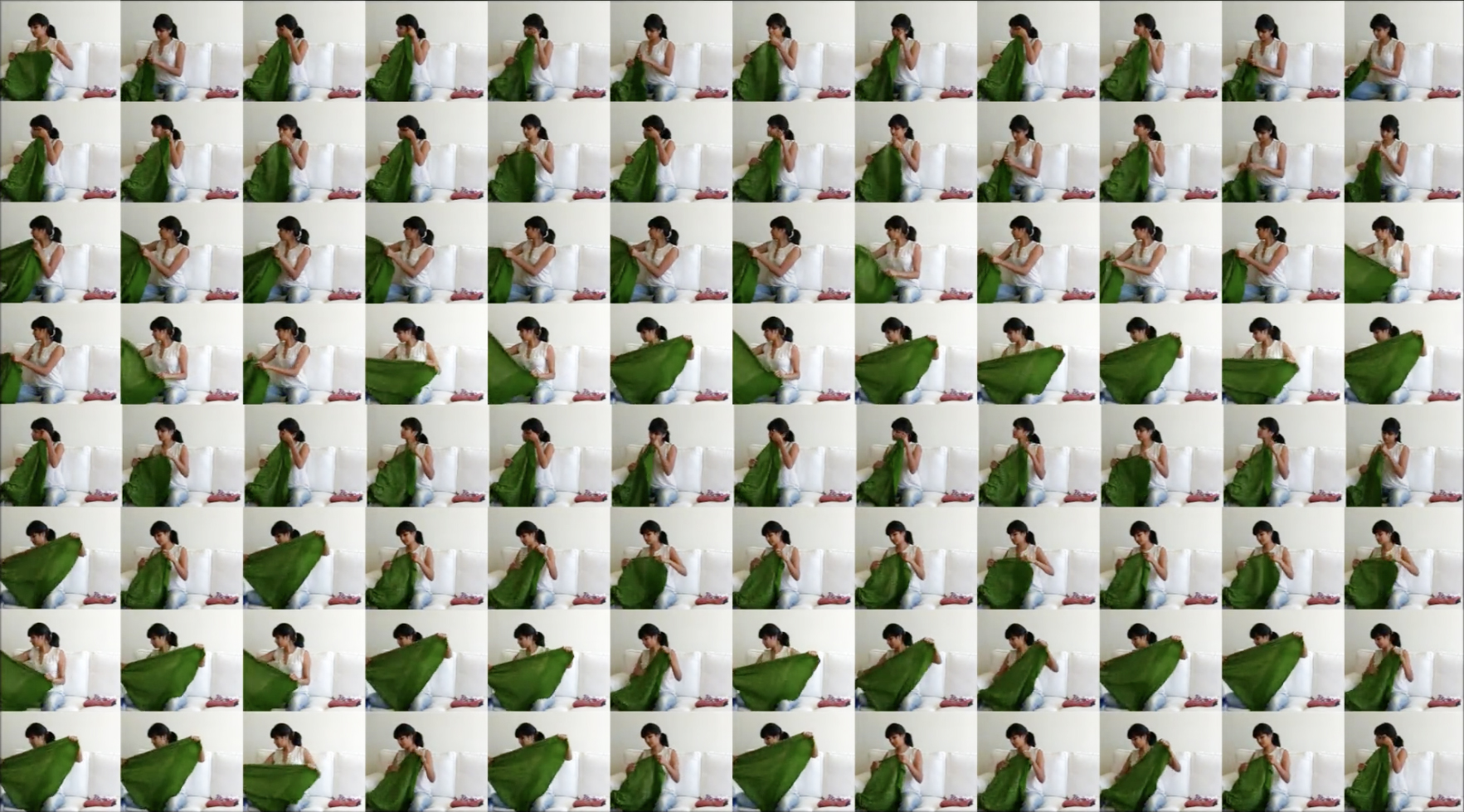

Surahi Saraf is a media artist whose work includes/ encompasses video installations, sculptures, performances, and sound. Her work Fold (2010) employs multiplication, repetition, and sound in a video of the artist folding laundry. Saraf grounds her audio works in her training in classic Indian music and dance. In this work, the artist creates a transcendent, immersive sound environment around her distorted humming, punctuated by the snap of cloth being straightened and folded. Saraf has said that she does not consider Fold a feminist work, despite its depiction of her performing a domestic task traditionally done by women. pzb

10. Mika Rottenberg

Mika Rottenberg, still from Spaghetti Blockchain, 2019, single channel video

In Mika Rottenberg’s video, Spaghetti Blockchain, scenes from an ASMR factory feature in a large chain of labor and production. ASMR is portrayed as a wondrous product but then also a solution born of Marxist nightmares. In a cyclical process, ASMR reorients senses that are fried as a result of alienation, with auditory experiments that trigger positive sensations in the body. Sound is a product that soothes the wounds of global production. It is a technological solution to the problem of too much technology. Rottenberg shows us a secret world, real or imagined–it doesn’t matter–that is layered with triggers for multiple sensations and a complex critique of global labor chains. aw