Knotting and Unknotting:

A Critical Examination of

Tibetan Carpets in Exile

Tenzin Tsomo

The carpet weaving industry in Nepal has seen drastic changes since its birth over five decades ago. From a small refugee-run weaving cooperative, it became one of two industries bringing the highest foreign currency into Nepal during the peak of its success. In the last sixty years Tibetan hand knotting has witnessed fluctuations of successes and failures. It has passed through the hands of Tibetan refugees to thousands of Nepali weavers today, changing the structure of both the business and the rugs themselves.

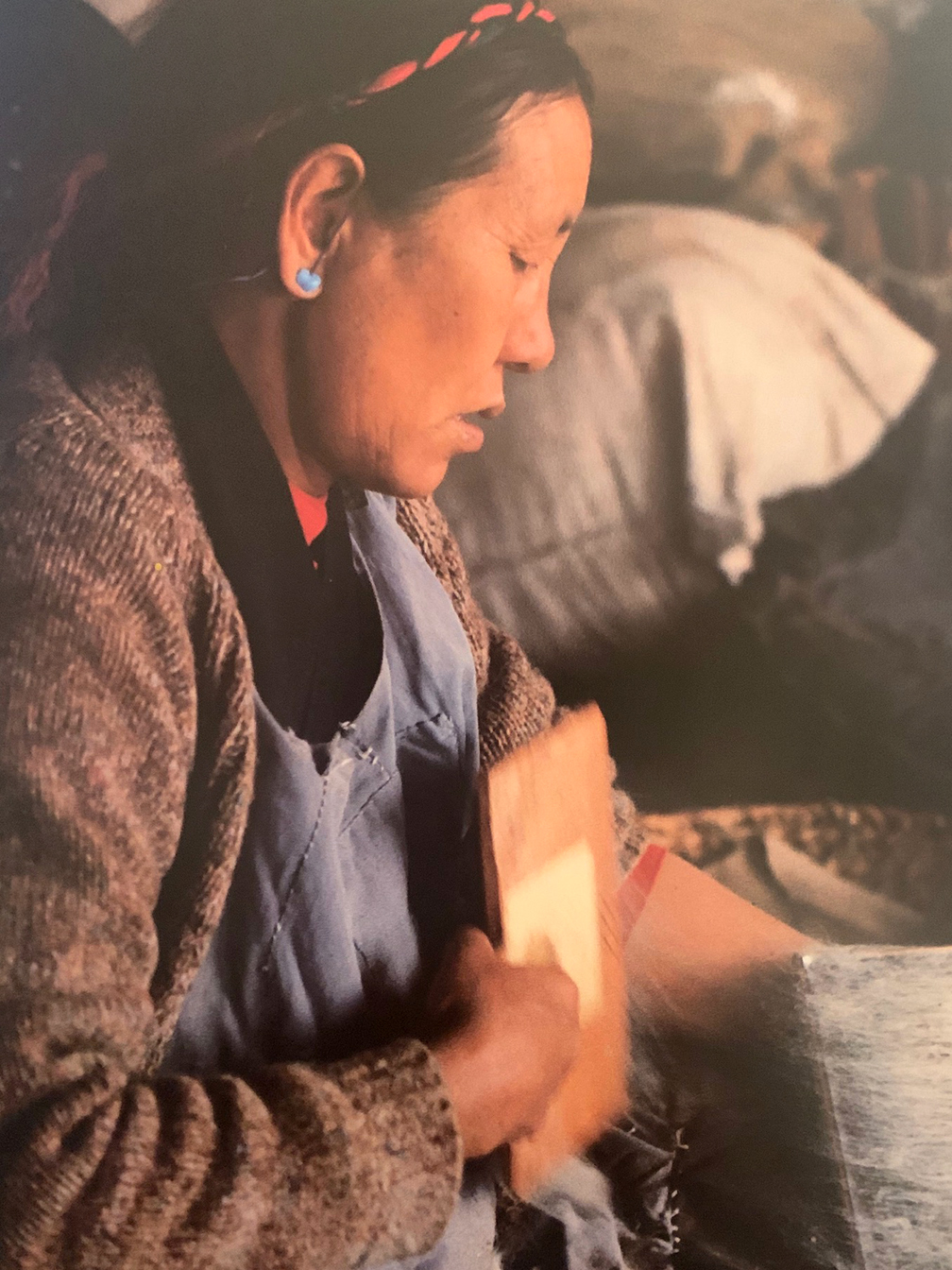

This photo is of my momo (grandmother) at the Jawalakhel Handicraft Center (JHC). It’s from a photo book titled, China The Beautiful by Manly Chin, but it was taken at the Tibetan Refugee Camp in Nepal, not in Tibet. The photographer writes, “Knotted Carpets are one of the traditional handicrafts of Tibet, the wool combed out by hand before it can be spun and woven. The light in this workshop was so dim that I had to use a wide aperture and very slow shutter speed- but not so slow that it turned the combing action into a blur.” Could he have imagined that one day her granddaughter would encounter this photograph at a bookstore in the US?

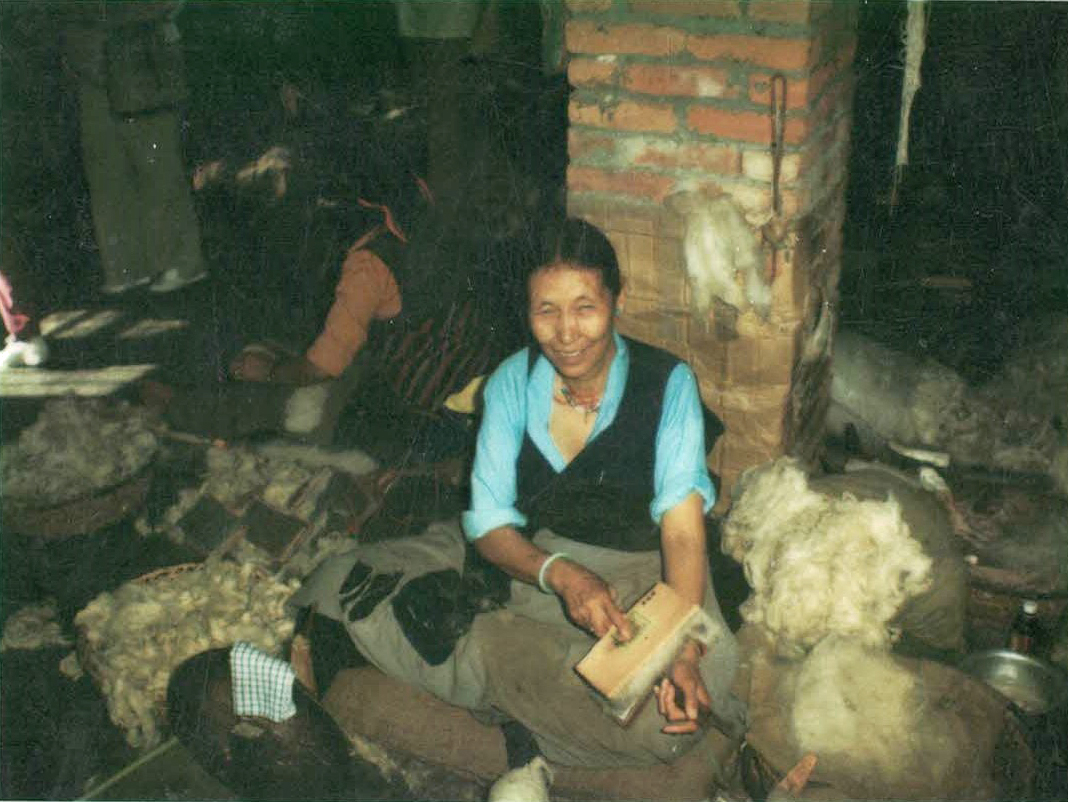

Also momo at the JHC in same dimly lit workshop that Chin describes in his book

Also momo at the JHC in same dimly lit workshop that Chin describes in his bookI am a weaver and also the daughter and granddaughter of Tibetan refugees, who were carders, spinners, weavers, dyers and eventually exporters of Tibetan Rugs. The hard labor my parents endured has offered me the benefit of an education that made many more spaces accessible to me. Although my parents intended to pave a different pathway for me, I am, nevertheless, tracing that same trail backwards, picking up fragments of weaving knowledge that they shed along the way.

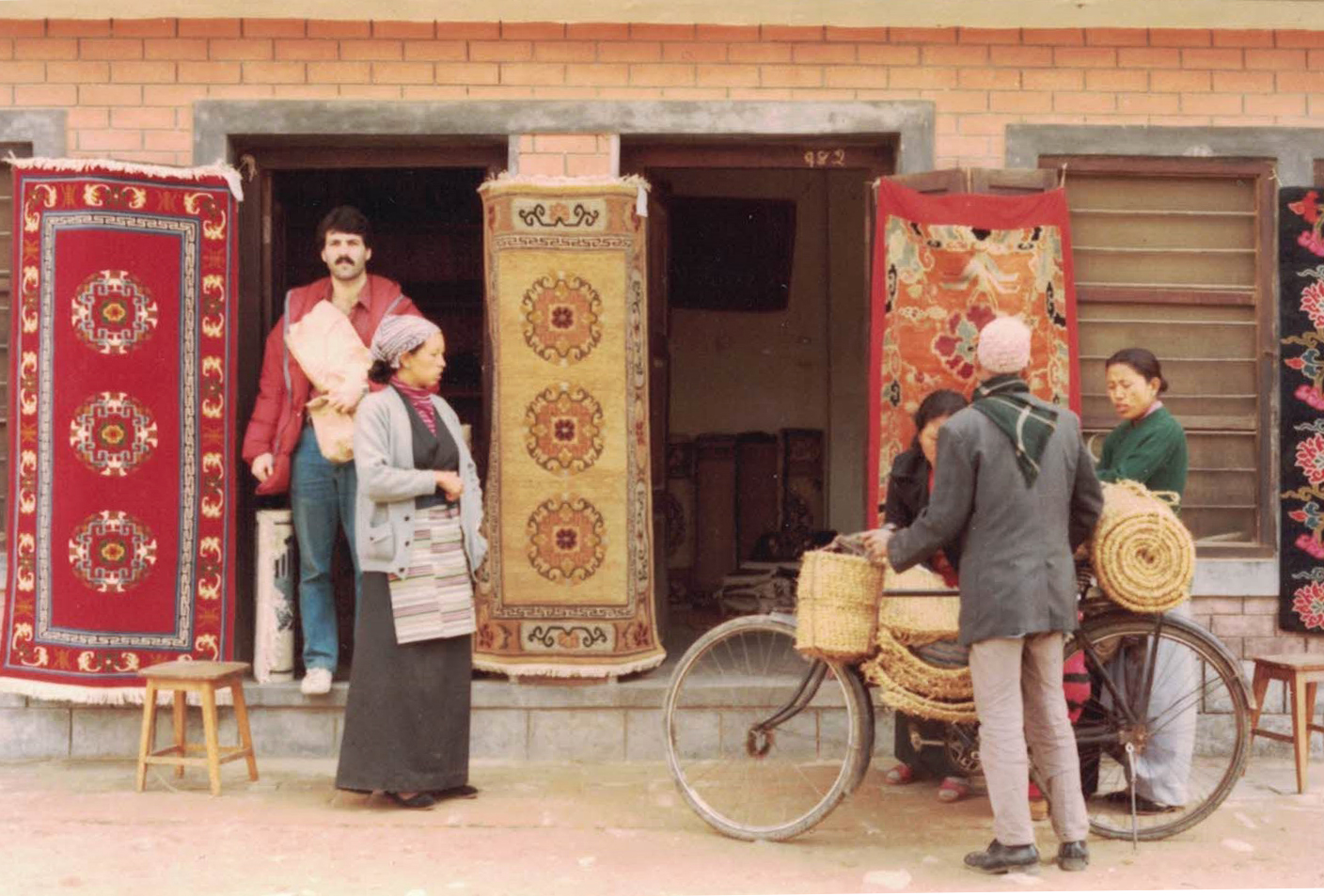

Outside my mother’s shop in Jawalakhel. She is second from the left. The tourist seen on the furthest left is probably the one who sent her this photo. She would often share her address with many tourists who bought rugs from her.

The path was not always easy to access. While weaving has transformed the lives and economy of Tibetan refugees, it was also back-breaking labor that traumatized many and triggered complex issues about refugee life that are complicated to discuss. It provokes strong feelings about labor, gender and class. This article barely scratches the surface of these conversations. However, I will look at key moments in its history, from a coveted skill kept within families in Tibet to the dissemination of that craft knowledge to Tibetan refugees and local Nepali artisans of recent.

Though carpet-weaving was an ancient heritage craft, most Tibetan refugees were pastoral nomads and had never kept carpets in their own houses. In Tibet, carpets were commissioned and afforded by the elite class, high government officials and monasteries. Only a few families of weavers in select provinces wove. The tradition was very secretive, passed down from one generation to another and tightly guarded within weavers’ families. However, unlike the contemporary Tibetan carpets woven today, these carpets reflected the aesthetic tastes, lifestyles and religious beliefs of the Tibetan society of the time. After the Chinese invasion in 1959, thousands of Tibetans fled their country to Nepal and India. The exile government was keen to find ways to train Tibetans with handicraft skills. Carpet weaving was one of those skills. For the first time, the craft became accessible to everyone in the diaspora who wanted to learn to weave.

Early photo of the workshop at the Jawalakhel Refugee Camp in Nepal. This was before the introduction of graphing paper. The weavers can be seen referencing the back of older rugs to reproduce designs (Photo from an online source: please see works cited)

At this time there were only a few master weavers in the community, and they led workshops around Nepal and India to teach carpet weaving skills to Tibetan refugees. The Jawalakhel Handicraft Center (JHC) was one of those workshops. It was set up in 1960 along with financial assistance from the Swiss Red Cross and Swiss Agency for Technical Assistance (SATA). By the 1970s, SATA also provided financial assistance to purchase rolls of graph paper enabling weavers to reproduce the designs without using the back of older carpets as a reference. Artists in the community were hired for their skills to paint graphs. This process was more efficient and practical, but it also removed the opportunity for weavers to grow their tactile sensibility when judging what kind of knots to use. These graphs were followed grid by grid and weavers predominantly started to use only one kind of knot. This allowed weavers to reproduce designs that were more uniform and suitable for the foreign market and introduced, for the first time, a standardized quality of Tibetan carpets in knots per square inch: 60 knots, 80 knots and eventually 100 to 150 knots per square inch.

Within a decade or two, more enterprising Tibetan families left the cooperative to start their own workshops. By this time the hand-knotted carpets were not just tourist souvenirs, but rather dominant features in the European design market. With higher demands, weavers trained more artisans to join them and together they expanded their practice, experimenting with chemical and natural dyes. By the early 2000s the advancement of technology enabled most of the designs to be graphed through professional design softwares. The capacity of playing with colors using computer software opened new possibilities of weaving on a bigger scale and designing rugs that were more complex, with the ability to resemble watercolor paintings even. Tibetan carpets today are mostly customized designs afforded by wealthy consumers in the West. They are frequently enormous in size using a range of 40 to 50 colors. Though unintended, over the decades we have slowly neglected our aesthetic agency, becoming carpet fabricators for the design world.

The effect of the new carpets is undeniably impressive compared to the simple four and five color traditional motifs produced in the past. However, the difficulty of weaving more enormous carpets with a myriad number of colors comes with a compromise, namely the “uncrossed” carpet. A traditional hand-knotted carpet has a plain weave (a weft thread alternating over and under the vertical warp threads) that is woven between every line of knots to secure them together. This construction ensures the durability of the carpet. Without the security of the plain weave between the knots, it is just a low-quality carpet using the highest quality materials and highly skilled artisanal labor. Sadly, most Tibetan hand-knotted carpets woven today in Kathmandu are uncrossed carpets.

With the popularity and marketability of Tibetan hand knotted carpets in the high-end design market, the industry was always susceptible to being shaped by the trends of the design world. Despite, or more likely because, of its popularity, aspects of the traditional knowledge and skills have been diluted down over time, for both efficiency and to meet the standards of the market. With so many structural changes made to the unique process of Tibetan-knotting, how are each of us in the supply chain complicit in harming and endangering the tradition of the craft? Whose voices are shaping the future of contemporary rug making, and how has incorporating industrialized standards into this craft industry resulted in further alienating artisans from their work?

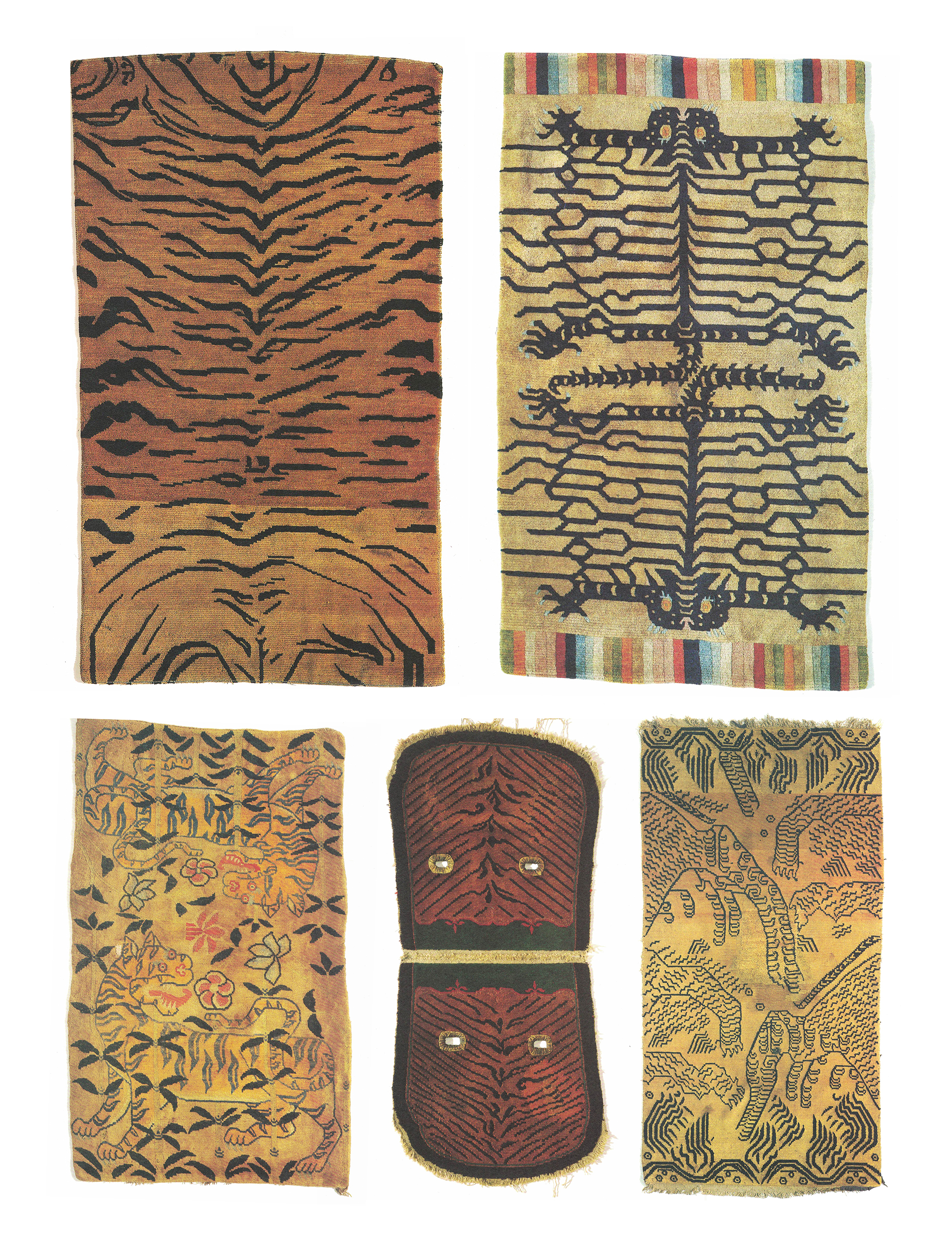

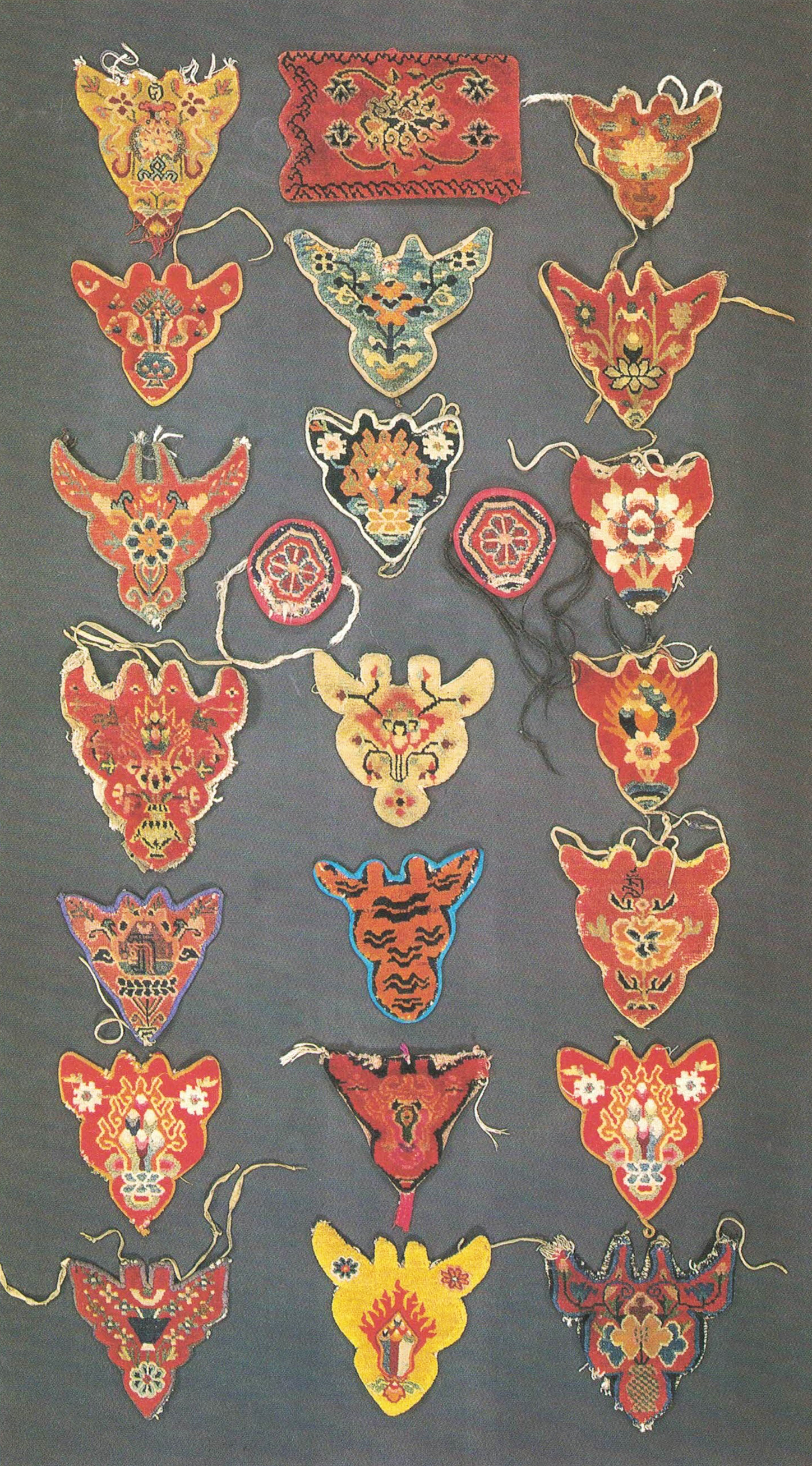

The tiger motif is a very popular Tibetan design as they were used in monasteries to act as guardians but were also a symbol of power and wealth. These plates are from Mimi Lipton’s The Tiger Rugs of Tibet (see works cited for full reference). One is an example of a Tibetan equestrian rug placed under the saddle of horses. These tiger rugs show the creativity of the weavers who’ve interpreted the representation of a tiger in a wide variety of ways- both playful and distinctively original.

I consider weaving as akin to a native language. It is one of the few traditions that we’ve inherited in exile. It is a language of survival. A language that is woven with our stories and the histories we lived through. The first generation of Tibetan weavers and entrepreneurs in exile embraced innovations and changes because their livelihood depended on it. They worked within the framework of a manufacturer and catered to the rapidly changing markets they served. It is the task of the next generation of artists, creatives and entrepreneurs to claim ownership of our craft, revive lost skills and invest in building more decentralized business practices that also prioritize creative collaboration within our own communities. To create more possibilities for our future, our artisans must be trained not just in skill, but also offered agency to exercise their creativity and voices. We need to reclaim carpet weaving as a culture and acknowledge the richness of this artistic lineage. It is critical that we challenge the values of both the past and the present repeatedly so our creativity for rug- weaving can emerge back from the shadows and evolve on its own path.

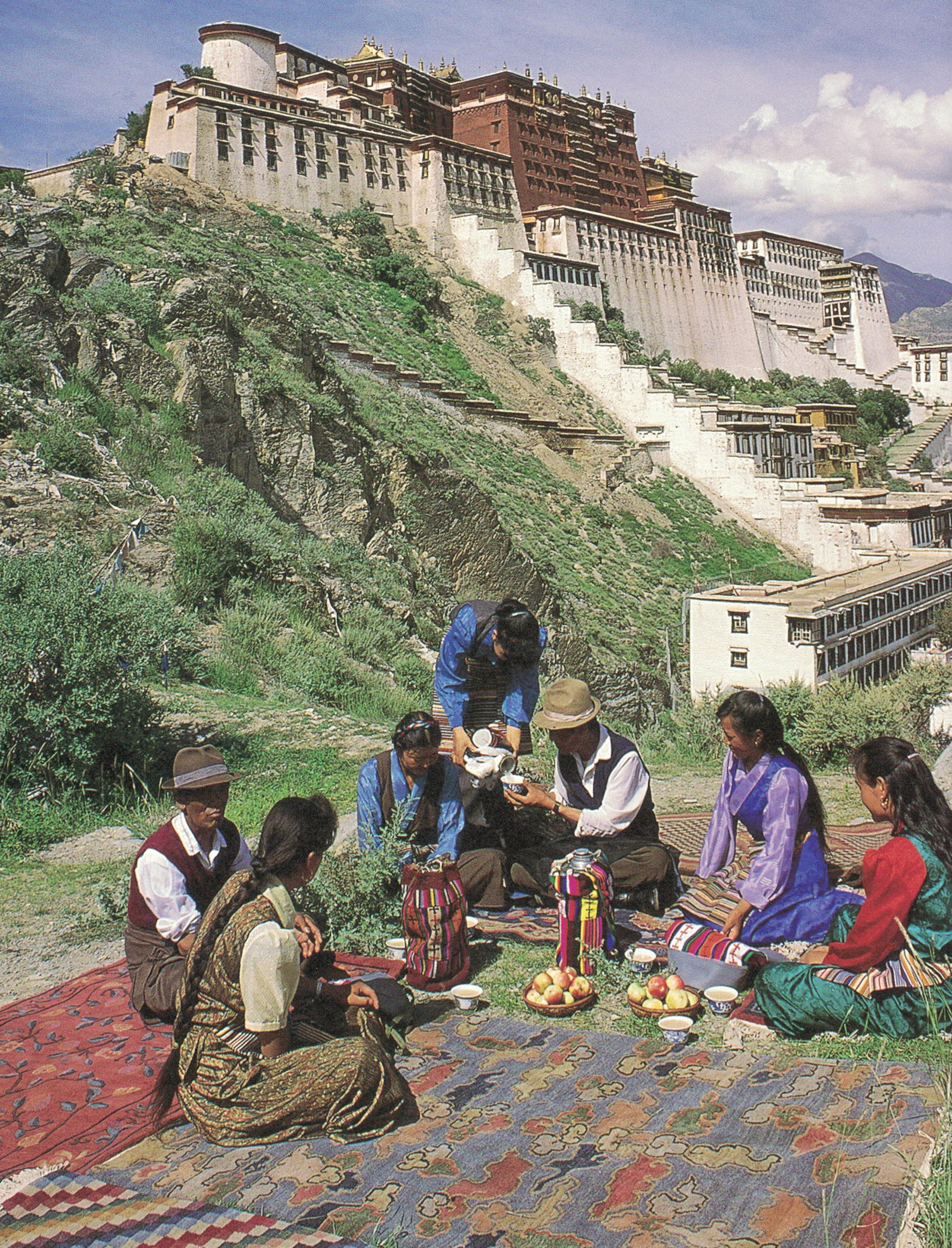

This is a photo outside the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet. Though rugs are used mostly at homes, it is very common to see rugs laid out for picnics, weddings or any other celebrations. (Source: Of Wool and Loom: The Tradition of Tibetan Rugs)

This is a photo outside the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet. Though rugs are used mostly at homes, it is very common to see rugs laid out for picnics, weddings or any other celebrations. (Source: Of Wool and Loom: The Tradition of Tibetan Rugs) Rugs are not only woven for the home, smaller masks were also woven as

Rugs are not only woven for the home, smaller masks were also woven asdecorations for horses and mules known as takyabs.