Community leader and civil rights activist Estelle Witherspoon (1916-2001) served as the first manager of the Freedom Quilting Bee, and her home served as the initial base for the group. Photograph by Nancy Callahan

Community leader and civil rights activist Estelle Witherspoon (1916-2001) served as the first manager of the Freedom Quilting Bee, and her home served as the initial base for the group. Photograph by Nancy CallahanThe Freedom Quilting Bee:

Textile Art and Mutual Aid

in the Civil Rights South

Aja Bond

In Wilcox County, at the rural center of Alabama, a remarkable convergence of political, economic and artistic innovations gave rise to a new vision of self-determination and social transformation that would forever change the lives of the communities that lived there.

In 1965 the national Civil RIghts movement had become focused on the Black Belt, a place named both for its rich fertile soil, and because it was home to many African American share-croppers who lived and worked in extreme poverty. Amidst an atmosphere charged by racist murders and police violence which would prompt President Johnson’s legislation protecting voting rights, the black community and their allies responded with counter-demonstrations and perhaps most memorably, a four day march from Selma to Montgomery led by Martin Luther King Jr. Black residents experienced targeted economic repression by landlords, business owners and banks, finding themselves suddenly evicted or required to pay back loans or store credit in full as a direct result of their participation in these demonstrations for voting rights, as was often communicated to them directly. These events, and the increasingly dire conditions that led to them, contributed to this region being the focus of daily news headlines across the country over the spring and summer of that year. It is from within this crisis that an incredible group of talented black women artists came together and built a network across the country that enabled a thriving community project in Wilcox County, Alabama, known as the Freedom Quilting Bee (FQB).

Estelle Witherspoon, 1980 Photo by John Reese

Quilting had always been a form of creative expression, resourcefulness, care and beauty in African American communities. Quilts were made by piecing together scraps, cast-off old clothes and waste products from textile factory work, then lovingly and fastidiously hand pieced and often collectively quilted in what’s known as a “Bee”. Before the community had a purpose-built space, they would gather together in each other's homes to collectivize the labor of completing a quilt, which was practical and also served as a celebration. In homes such as that of civil rights activist and future FQB leader Estelle Witherspoon, the women from this and neighboring communities created their own distinct styles and innovative interpretations of classic designs. Gee’s Bend, a now well-known community of visionary quilters, isolated within a large bend of the Alabama River, was a short car and ferry ride from the Freedom Quilting Bee, and many of its members came from the FQB to participate in the project. Before it was established, the FQB women made quilts for their families and friends, and if for some reason they were able to find buyers, they got $5 for a quilt (equal to about $40 today) which would have required weeks of labor. Things would change for these artists as the confluence of events and civil rights activism that was occuring in the area brought not only media attention but also newcomers showing up looking to be of help. This in part made it possible for new connections to be forged in the midst of so much upheaval which allowed for radical new possibilities for the lives of these women and their families.

Members of the Freedom Quilting Bee display their quilts, circa 1966.

Courtesy of Birmingham Public Library Archives

While the Freedom Quilting Bee cooperative was first and foremost the result of the women who created the beautiful quilts and worked to build and run the organization, it may not have happened without a number of people and groups who contributed time, social connections, services, materials, and other resources to the project. The Selma Inter-Religious Project (SIP) and the Selma Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) were central to the local civil-rights organizing at the time and much of the initial resources for buying the quilts came from their extended networks. One of the people who helped the FQB to grow was Father Walter, a white Episcopalian Minister who was denied work, loans and even the right to adopt children in Alabama for years because of the interference of a Bishop who took issue with his anti-racist interpretation of the gospel. It was Father Walter, who, while working for the civil rights movement, arranged to have the quilts auctioned at a hip photography studio in New York City and helped establish the initial connections with the art scene there, eventually leading to the promotion of the quilters and their work by abstract expressionist painter Lee Krasner, art historian and curator of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art Henry Geldzahler, interior designer Sister Parish, and long-time Vogue editor Diana Vreeland.

![]()

“Quilter’s Fancy” by Estelle Witherspoon n/d. Photo: Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

As the story goes, Father Walter was driving around Possum Bend with another civil-right activist working in Wilcox County when he saw 3 beautiful quilts hanging out on a line. Perhaps because of the influence of his wife who was a graduate student in art, or maybe owing to his time in Seminary school in NYC, he recognized that there was something about these quilts - the high-contrast graphic designs, the flare of color and style - that reminded him of the art world beyond rural Alabama. He and his friend got out of the car, hoping to speak to the artist who had made them but it seemed no one was home. Returning later with a local black woman, Ms. Saulsbury, who knew the quilter, Ora McDaniels, he realized that when she had seen two white men coming to her house, she had run into the woods to hide. The second encounter was smoothed by the presence of a mutual acquaintance and he bought a few quilts from her and a number of other women in Possum Bend. He bought them outright for $10 each and the sale of a ten-dollar quilt meant for most a 1% gain in annual income. He explained that he was going to have them sold at an auction in New York and would bring back whatever profits were made on top of the $10. As SLSC representative Reverend Dan Harrell recounted in Nancy Callahan’s book The Freedom Quilting Bee:

The people were in a win-win situation. Ten dollars was twice as much as they’d ever got for a quilt before. So if this crazy white man ever showed up again, it didn’t really matter. But my goodness if he actually was going to do what he said, rather unheard of for white people, that would be even better. What was there to lose? 1

When Father Walter returned with profits from the auction, as promised, it turned out they had everything to gain. As more and more women offered up quilts, some made to order, some pulled out of storage chests and directly off of beds, it became obvious to the community that this was a cooperative ready to blossom. They obtained free services from a lawyer, and on March 26, 1966, within one year of Martin Luther King Jr’s famous march across the Black Belt, 60 quilters came together to adopt a charter, elect officers and establish this organization that would change Wilcox county and the lives of so many of the people who lived there.

Groundbreaking at FQB site in March 1969

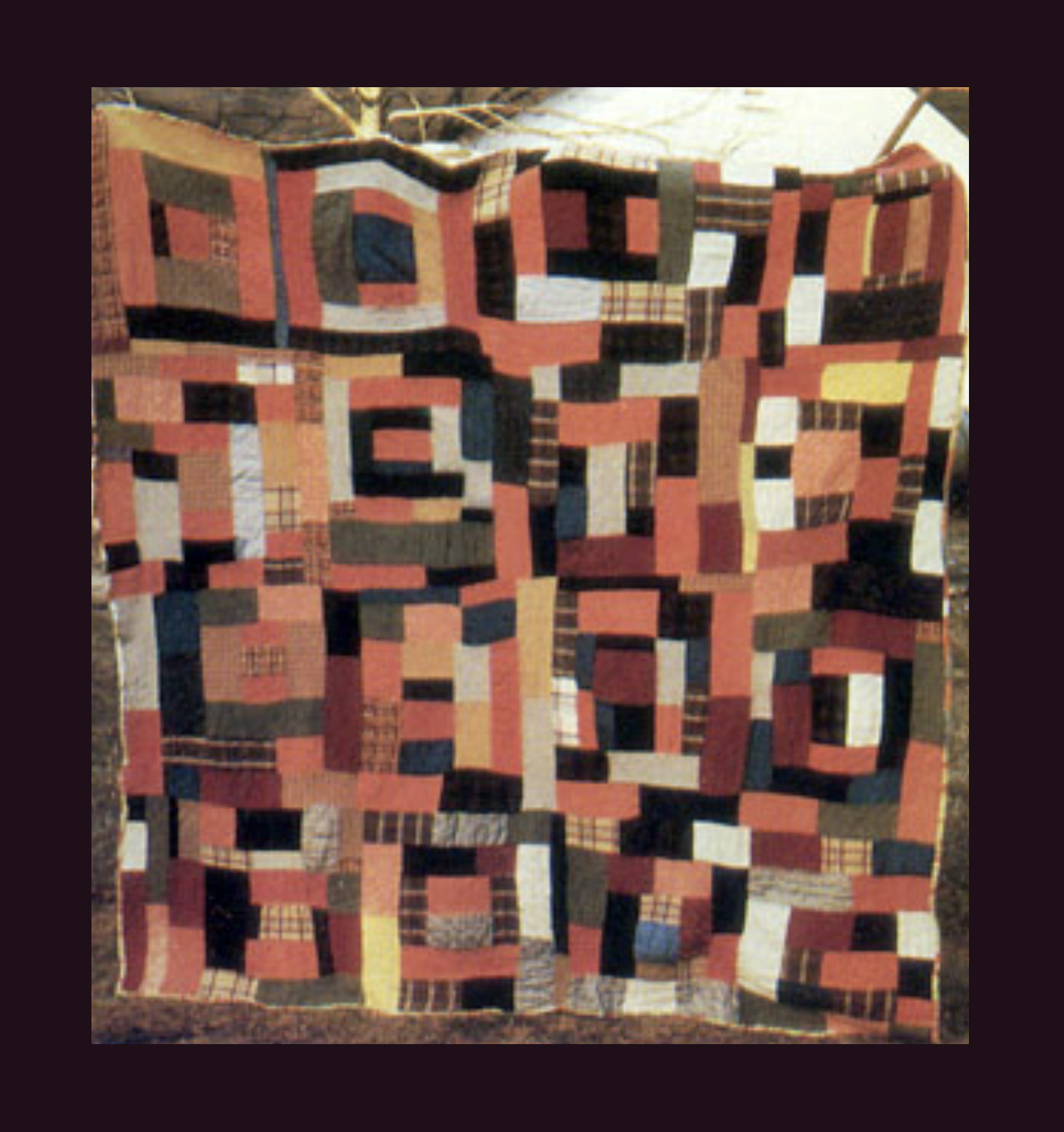

All-wool crazy quilt made for the Freedom Quilting Bee by Minsie Lee Pettway. Photograph by Nancy Callahan

All-wool crazy quilt made for the Freedom Quilting Bee by Minsie Lee Pettway. Photograph by Nancy Callahan

The Freedom Quilting Bee: Folk Art and the Civil Rights Movement by Nancy Callahan

What began as an informal group of quilters with unlikely connections to well-positioned people led to a robust workers-cooperative which enabled the women to buy land, build a large sewing studio with a built-in daycare center, and sell small parcels of the land to provide housing to members of their community who had been displaced in the fight for voting rights. The Civil Rights movement brought an unexpected influx of resources and media attention to a poor rural African American community. Understanding that this moment might never come again, the women of this community, aided by those people who were determined to offer what support they could, tenaciously seized their opportunity and established a means for their community to mutually flourish.

Freedom Quilting Bee site with members and RDLN visitors

For more information visit:

https://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/gees-bend-quiltmakers

http://www.ruraldevelopment.org/FQB.html

1. Nancy Callahan, The Freedom Quilting Bee, (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1987) p. 14