Anita Corbin, London, 1980s

A brief and incomplete historical context of an early punk subculture as seen through its clothing

Amanda Walters

From its start, punk culture was marked by a rejection of oppressive heteronormative values and lifestyles. It began in the late 70s as a music genre, but was also more than just the sum of its musical contributions. The subculture was as visual as it was aural. Like the audible facets, its visual contributions were embedded with subtle and not so subtle connotations of violence: ransom note inspired graphics, modified military clothing, and the aesthetics of weapons found in chains and spikes. In all forms it embodied a spirit of protest. Its early form was also very much aligned with its queer cultural contemporaries. The two subgenres fed each other and overlapped often. That early punk culture proposed a rejection of the confinements of gendered representation, and most notably, a rejection of masculinity.

An analysis of clothing so easily runs the risk of being reductive on one side, or dismissive on the other. Looking at the cultural and economic history of the birth of a movement offers insight to cultural conditions that affected more than one subcultural group. Subcultures form in response to a parent culture, and often from a position of opposition to the problems of that parent culture. It would also be hard to claim a singular narrative to the historical context of punk culture. It emerged simultaneously in many locations, each with their own political conditions: in East Germany punk culture was a radical representation of the angst and opposition to the repressive DDR; the United Kingdom elected the ultra conservative Margaret Thatcher in this era; the United States elected Ronald Regan; and for both the UK and the US, late stage capitalism was in full swing.

Chaos Days, Hanover, 1984

The shifts that led to the conditions that gave birth to the movement began much earlier, just after WW2. Shifts in socio-economic structures in the US and UK led to the alienation of the working-class. The structures that once supported the working-class were embedded in the layout of the working-class neighborhood: access to extended kinship and the solidarity of the working-class community. As housing redevelopments like high-rise apartment buildings replaced the former self sustaining neighborhood layout, i.e. the cornershop, family businesses, pubs, and communal space, the new working-class was fragmented by its isolation from extended kin and community.

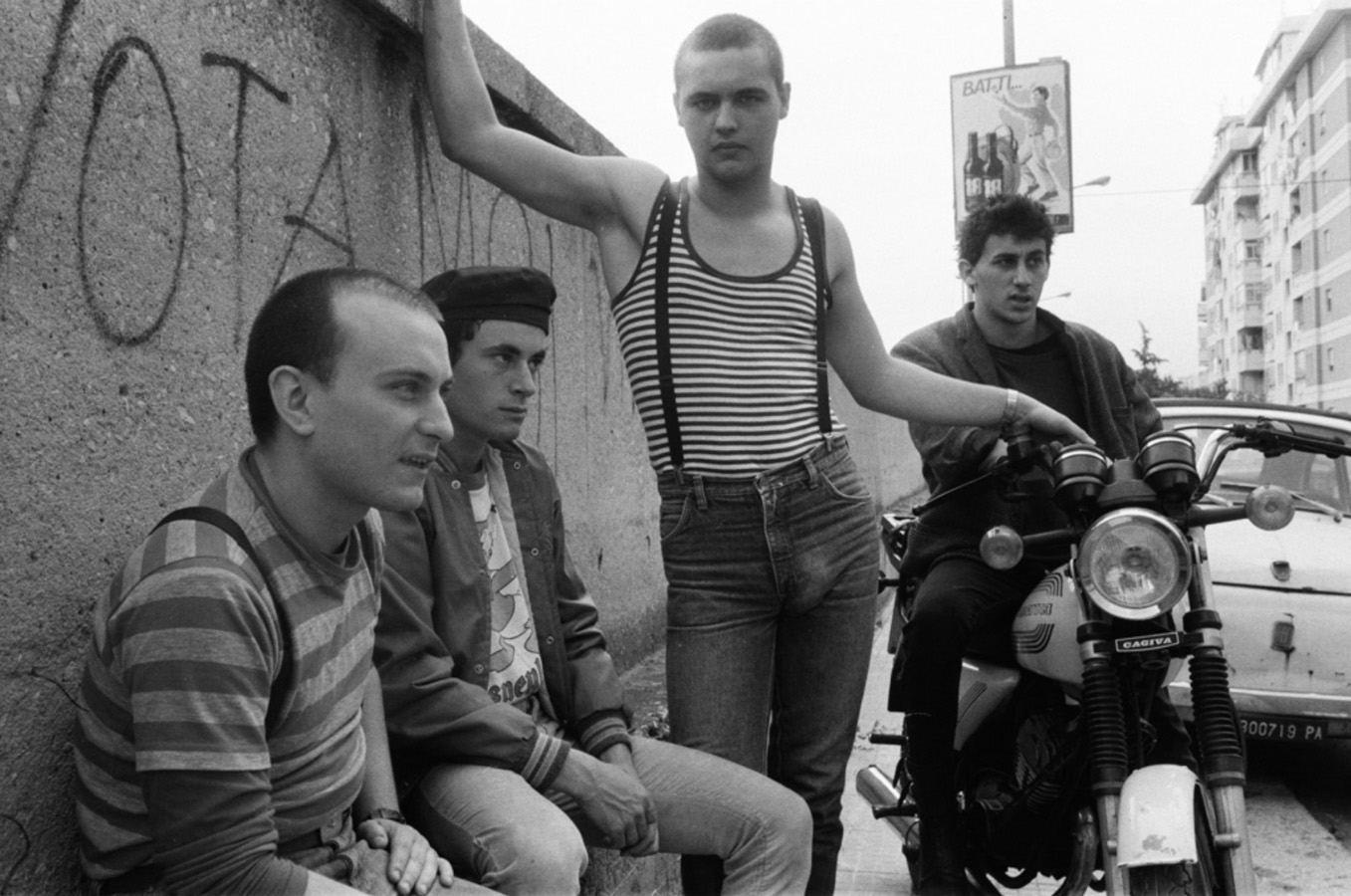

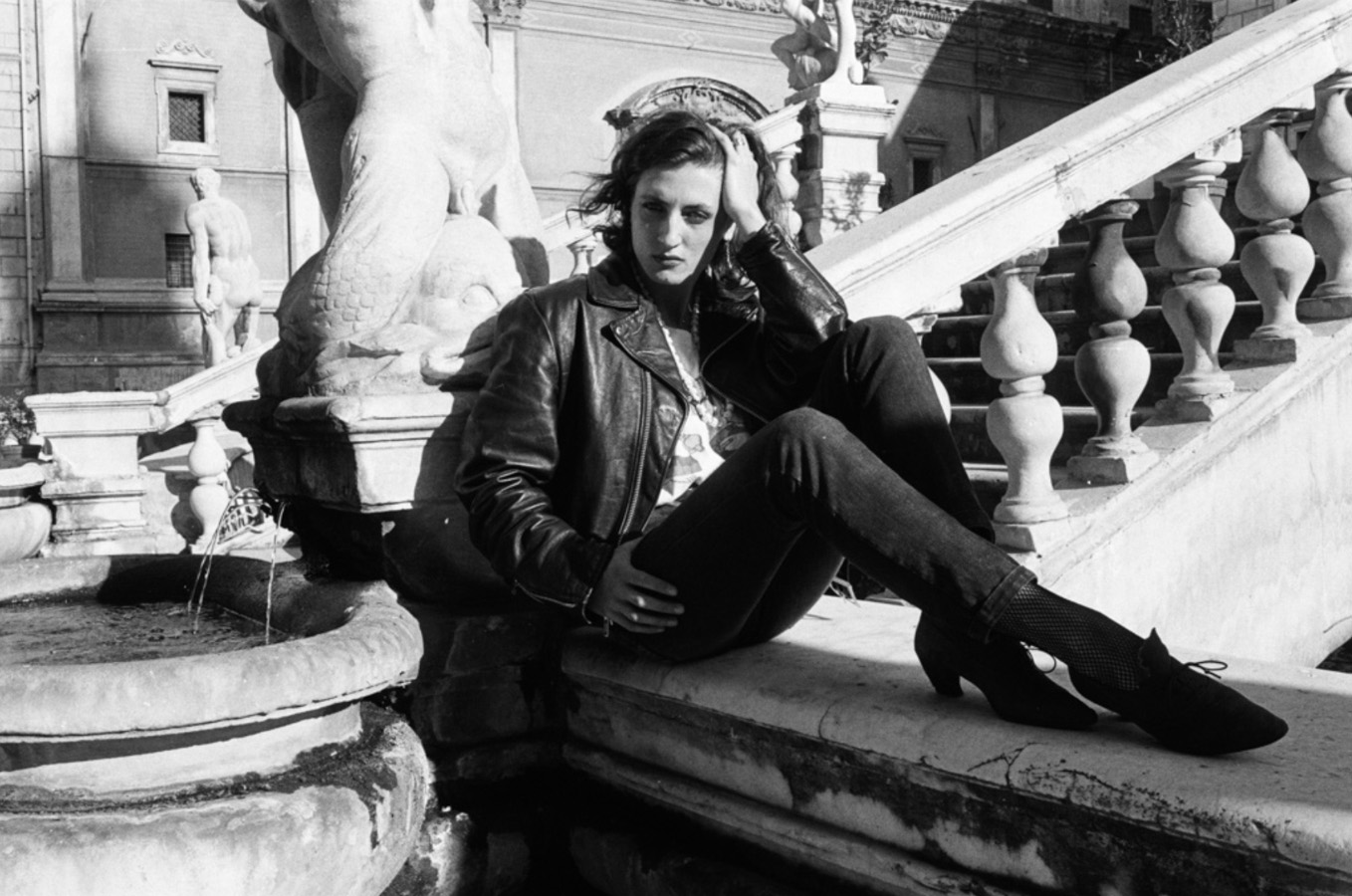

Italy, 1980s, photos by Fabio Sgroi

This state of alienation birthed new communities, often in the form of subcultures. One such subculture, punk was a leftist working class faction. In its rejection of a dominant consumer culture it was known for its DIY aesthetic. Home made clothing, spray painted band shirts, and jewelry made of household objects like safety pins, upended any reverence to authenticity. A penchant for androgynous style was among the aspects that separated it from the right wing working class skinhead culture. Cloth communicated these differences. It was the signifier for a group of connotations that separated it from its parent culture, and simultaneously explained why. Clothing acted as a visual form of cultural protest.

DOA concert at The Starwood, Los Angeles, 1981

DOA concert at The Starwood, Los Angeles, 1981

Prick up your ears, T-shirt design,

Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood for Seditionaries, 1979

Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood for Seditionaries, 1979