![]()

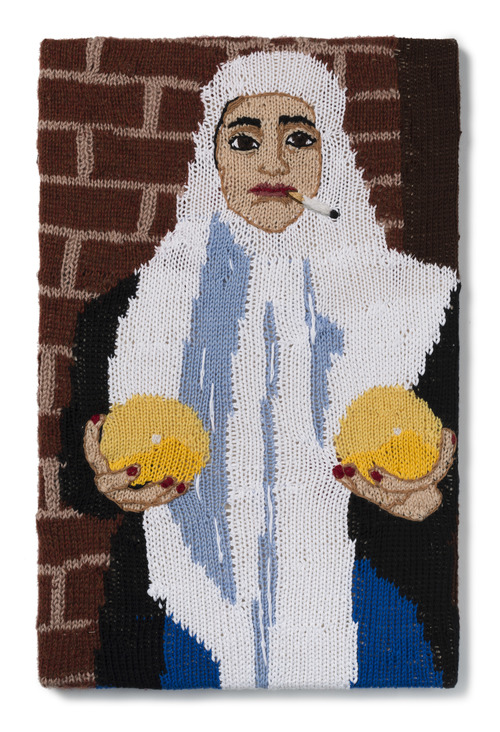

Kate Just, Feminist Fan #20

(Nan Goldin, Nan, one month after being battered, 1984), 2016

Feminism, Fandom, Devotion,

and Sincerity

in Kate Just’s

Feminist Fan Series

From 2014 to 2017, American-born Australia-based artist, Kate Just hand knitted replicas of iconic self-portraits of feminist artists and activists in a series called Feminist Fan. The portraits are soft, graphic, and almost cartoonish at first glance, with the reductive palette, limited definition, and the lumpy edges inherent in the medium. They are child-like in both their aesthetic and content, in the sense that they borrow the style of comics, and are so simple, to the point, and sincere. But, it’s also that devotional fandom is so much more prevalent in childhood. Why is this? Why is sincerity so associated with naiveté? At a moment to so ripe with devastation and the demand to articulate so clearly all the injustices of our civilization, sincerity and fandom are a refreshing experiment in a sensory muscle that is beginning to atrophy, hope.

The form which at first adds to its cartoonishness makes visual the labor of its making. The labor reads as a sign of devotion, the slow process of knitting turns each work into a meditation on the artist Just portrays. Which elements of the image that are included and which aspects that are flattened highlight the narrative Just most puts forth. In her portrait Pussy Riot storming Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, 2012, Just highlights the contrast of their brightly pigmented dresses and tights against the beige hues of the church. The new and invigorating image of future is set against the old drab hues of the oppressive building of the past.

The works are given another life outside the gallery by circulation on the internet. Using the handle @katejustknits, Just shares each portrait on Instagram, adding the series name as hashtag, #feministfan. Through circulation these works become activist agents. The hashtag becomes an archive of not just the works, but also the community of feminists that repost. The tag is used mostly by Just, herself, and the institutions supporting the work, but it is also sprinkled with other feminist fans sharing the work.

Kate Just, Feminist Fan #3

(Pussy Riot at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, 2012), 2015

(Pussy Riot at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, 2012), 2015

Kate Just, Feminist Fan #18 (Yoko Ono, Cut Piece, 1965), 2016

Kate Just, Feminist Fan #9 (Sarah Lucas, Self Portrait with Fried Eggs, 1996)

Version 2, 2015

Version 2, 2015

On the Instagram posts, each portrait is accompanied by a narrative describing Just’s reflections on the original portraits. The narrative layer, also simple and not complicated at all, shifts the reading of these works from cartoons to alters. They offer an earnest and subjective lesson in feminist art history. To accompany her portrait of Sarah Lucas, Self Portrait with Fried Eggs, 1996, Just writes:

“This is my favourite of her self portraits. In this picture, Lucas may appear to be lounging in the studio but she’s actually working hard – to challenge and subvert the male gaze! With fried eggs suggestively placed over her breasts and green t-shirt, her legs spread wide and a tough and questioning look into the camera, Lucas deconstructs conventional depictions of women as objects and takes the piss out of the usual image of the modern male artist at work. Androgynous, defiant and seriously cool, Sarah Lucas makes me want to smoke, glare, wear impossibly high waisted jeans and take over the art world. Sarah Lucas, I’m your feminist fan!! #sarahlucas # feministfan”

Each narrative offers a thoughtful analysis of the work and artist, and also Just’s relationship to the work, reminding the reader that these works are subjectively experienced- in itself a feminist lesson.

The series is a reminder of the work that has been done before and is ongoing. Each self-portrait portrays not just the artist, but also the artist working to complicate narratives of identity, whether gendered, religious, or normative values. Likely, this was the goal of the project, but what comes forth most for me is a contagious spirit of admiration and a non-nostalgic version of seeing the good in the past. The work reminds me how to see something the way I first saw it, before familiarity flattened its impact. Something changes when I look at Nan Goldin with a black eye depicted through yarn. The violence of the image seems even more violent when it looks like it is cut from a festive sweater, and I’m rethinking about the original work with a new urgency.

Kate Just, Feminist Fan #24 (Catherine Opie, Self Portrait/Nursing (2004), 2016