Shannon Finnegan, Do You Want Us Here or Not, 2020. Baltic birch, poplar wood, plastic laminate, 73.5" x 27" x 35.5". Images by Justin Wonnacott.

[A blue bench sits against a short white wall with four metal barriers beams, on the back of the bench in white text it reads: It was hard to get here. On the seat of the bench it reads: Rest here if you agree.]

[A blue bench sits against a short white wall with four metal barriers beams, on the back of the bench in white text it reads: It was hard to get here. On the seat of the bench it reads: Rest here if you agree.]

I struggle against the neoliberal demands for productivity. I am not a machine; my body is not mechanized. I have to rest. A lot. I am rest-resisting1, lying in my bed, writing about the demands of capitalism.2

As it is eloquently phrased by Carolyn Lazard, “When we are sick, we enact unintended resistance to an economic system that privileges efficiency over resilience.”3 Disabled artists are well acquainted with the body's need for rest and must embrace alternate ways of being to create work in a world demanding inhumane levels of production. Artists Shannon Finnegan, Alex Dolores Salerno, and Carolyn Lazard have all integrated rest into their practice and art, prioritizing the needs of the body over the rigorous, unrelenting expectations of the body under capitalist production. Their work elevates and politicizes rest. Rest as protest. Rest as refusal.

During the beginning of the pandemic, everything slowed down to a pace that matched my own. For a short time, our society was on crip-time.4 Crip-time is common slang referenced by disabled people when they are not ‘on time.’ It is time affected by ableist structures and ideologies. Crip-time could mean that one needs more time because the relentless demands of capitalist production move too fast for their body-minds,5 or that someone might move or think slower (or faster) than what is considered ‘normal.’ It might be time affected by illness, or time stolen by the broken medical industrial complex (like waiting on hold with Medicare for hours), or time affected by barriers in our built environment, like broken elevators.6 Crip-time is an appeal for a flexible standard of punctuality, and for the extra time needed to get somewhere or do something, or as author Alison Kafer describes it, “a reorientation to time.”7 It is not an apology. It is time cut short, time taken away, time slowed, or time jumping. It can also be expansive and meandering. Kafer says, “Crip time is flex time not just expanded but exploded; it requires reimagining our notions of what can and should happen in time, or recognizing how expectations of ‘how long things take’ are based on very particular minds and bodies.”8 Capitalism has trained us to believe that we must push ourselves to keep up with the idealized productive body, but crip time challenges the need to maintain those unrealistic standards.

1. Rest as Resistance is politicized by The Nap Ministry and is rooted in racial and social justice, working to dismantle the effects of white supremacy and capitalism.

2. Leah Lakshmi Pipzna-Samarasinha talks about “Writing from my sickbed… is a time-honored crip creative practice.” in Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, 2018.

3 Carolyn Lazard, “How to be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity,” http://www.carolynlazard.com/

4. “Crip” is a political reclaiming of the derogatory label “cripple.”https://www.redbullarts.com/detroit/exhibition/sick-time-sleepy-time-crip-time-against-capitalisms-temporal-bullying/

5. Writer Eli Clare discusses the body-mind as a connected whole, instead of unrelated entities.

6. Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip, 2013

7. Ibid.

8. “”

2. Leah Lakshmi Pipzna-Samarasinha talks about “Writing from my sickbed… is a time-honored crip creative practice.” in Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, 2018.

3 Carolyn Lazard, “How to be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity,” http://www.carolynlazard.com/

4. “Crip” is a political reclaiming of the derogatory label “cripple.”https://www.redbullarts.com/detroit/exhibition/sick-time-sleepy-time-crip-time-against-capitalisms-temporal-bullying/

5. Writer Eli Clare discusses the body-mind as a connected whole, instead of unrelated entities.

6. Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip, 2013

7. Ibid.

8. “”

Time moves so slowly for me when I am in pain – society races by while I’m in bed. It is as though I am a time traveller with a roadside view of everything forgotten. Poet, writer, and performance artist Leah Lakshmi Pipzna-Samarasinha acknowledges the pain and oppression of the disabled body and also celebrates the joys found in the “secret bliss of bed.” She touts that spending more time resting allows for expansive dreamtime, that “tired people catch things people moving fast miss.” Slowing down is seen as a luxury by society, but it is actually an ignored necessity.9

During the pandemic, hundreds of thousands of people were sick and society slowed down to slow the spread of Covid-19.10 Everyone, supposedly, had more time to rest. Personally, I was too anxious to find the time restorative and healing, although it was a welcome relief from the grind of commuting here and there. But after a few months, everyone went back to work – from home – and our place of rest became a place for work, and work bled into even more facets of our lives. And now, with things “getting back to normal,” the pace of society seems even more unattainable.11 Is it because we became used to resting without FOMO?12 We didn’t feel left out, because everybody else was at home, too. Short spurts of socialisation are now even more exhausting than I remember. Have we become homebodies and hermits, after spending over a year in isolation? I am exhausted. Even during the writing of this article, I had to repeatedly readjust and postpone for rest and grief. As a disabled person, who thinks a lot about time, and adamantly wants to challenge capitalist demands of productivity, I still find myself worrying over deadlines and guilt due to internalized ableism. Confronting and unlearning socialized expectations is a constant practice. I cannot physically keep up. I spent the day in bed with a migraine, constantly trying to convince myself I was well enough to write. Every hour or two, I would get up to get to work, only to realize the pain was still there. Even though I knew I was suffering from heat intolerance, I would question if I was really fine but coming up with excuses to procrastinate.

During the pandemic, hundreds of thousands of people were sick and society slowed down to slow the spread of Covid-19.10 Everyone, supposedly, had more time to rest. Personally, I was too anxious to find the time restorative and healing, although it was a welcome relief from the grind of commuting here and there. But after a few months, everyone went back to work – from home – and our place of rest became a place for work, and work bled into even more facets of our lives. And now, with things “getting back to normal,” the pace of society seems even more unattainable.11 Is it because we became used to resting without FOMO?12 We didn’t feel left out, because everybody else was at home, too. Short spurts of socialisation are now even more exhausting than I remember. Have we become homebodies and hermits, after spending over a year in isolation? I am exhausted. Even during the writing of this article, I had to repeatedly readjust and postpone for rest and grief. As a disabled person, who thinks a lot about time, and adamantly wants to challenge capitalist demands of productivity, I still find myself worrying over deadlines and guilt due to internalized ableism. Confronting and unlearning socialized expectations is a constant practice. I cannot physically keep up. I spent the day in bed with a migraine, constantly trying to convince myself I was well enough to write. Every hour or two, I would get up to get to work, only to realize the pain was still there. Even though I knew I was suffering from heat intolerance, I would question if I was really fine but coming up with excuses to procrastinate.

9. Actually, all bodies require rest. More rest than the demands of capitalism acknowledge or allow.

10. Kind-of

11. Will the accessibility that has been implemented during the pandemic, such as being able to work from home, in bed, continue? Or was it only for the comfort of the able-bodied? Disabled people have been begging for these accommodations for decades, and many of us are afraid they will be taken away as quickly as they were rolled out.

12. “Fear Of Missing Out,” an acronym used in slang to describe a feeling of anxiety or jealousy when other people are doing things together without you that might be fun or create a bond.

10. Kind-of

11. Will the accessibility that has been implemented during the pandemic, such as being able to work from home, in bed, continue? Or was it only for the comfort of the able-bodied? Disabled people have been begging for these accommodations for decades, and many of us are afraid they will be taken away as quickly as they were rolled out.

12. “Fear Of Missing Out,” an acronym used in slang to describe a feeling of anxiety or jealousy when other people are doing things together without you that might be fun or create a bond.

Navild Acosta and Fannie Sosa, Black Power Naps: Black Bean Bed, (2018)

Navild Acosta and Fannie Sosa, Black Power Naps: Black Bean Bed, (2018) . Image courtesy Red Bull Arts Detroit

[Shiny gold foil sunbeams encircle a round pool of chocolate brown beans. Traces of footprints are left in the pool, and the sunbeams catch the light. The installation is center-lit in a dark room, and sepia-toned paintings are barely visible in the background. A purple pillow sits in the pool/bed and lavender sprigs hang from the ceiling.]

Between 2017 and 2020, the curator Taraneh Fazeli organized several iterations of a travelling exhibition called Sick Time, Sleepy Time, Crip Time: Against Capitalism’s Temporal Bullying.13 The exhibitions included public programs and community projects addressing the politics of health and care, rest, crip-time, and illness rooted in disability justice14 that “prompt us to re-imagine collective forms of existence as life under capitalism becomes impossible.”15 For the exhibition, the artists Navild Acosta and Fannie Sosa presented Black Power Naps, a project that addresses the racial sleep gap by creating a space to prioritize respite for black visitors. Visitors can rest as reparations in a pool of black beans encircled by giant gold foil petals – a nest of sunbeams. I imagine the beans were cool to the body, providing a spa-like experience.

![]() Carolyn Lazard. Support System (for Park, Tina, and Bob), 2016. 24 gifted bouquets, documentation of performance and collectively-produced sculpture, dimensions variable.

Carolyn Lazard. Support System (for Park, Tina, and Bob), 2016. 24 gifted bouquets, documentation of performance and collectively-produced sculpture, dimensions variable.

[An installation shot of several bouquets sitting in glass jars on a wooden table. Behind them, a blank white wall flanked by inset bookshelves lined with books and other personal ephemera. AltText courtesy of the artist's website.]

Carolyn Lazard. Support System (for Park, Tina, and Bob), 2016. 24 gifted bouquets, documentation of performance and collectively-produced sculpture, dimensions variable.

Carolyn Lazard. Support System (for Park, Tina, and Bob), 2016. 24 gifted bouquets, documentation of performance and collectively-produced sculpture, dimensions variable.[An installation shot of several bouquets sitting in glass jars on a wooden table. Behind them, a blank white wall flanked by inset bookshelves lined with books and other personal ephemera. AltText courtesy of the artist's website.]

13. https://redbullarts.com/detroit/exhibition/sick-time-sleepy-time-crip-time-against-capitalisms-temporal-bullying/

14. Disability Justice is a framework initiated by Sins Invalid that centers and prioritizes multiply marginalized bodies, esp. disabled LGBTQ+ and BIPOC folks.

15. https://theluminaryarts.com/exhibitions/sick-time

14. Disability Justice is a framework initiated by Sins Invalid that centers and prioritizes multiply marginalized bodies, esp. disabled LGBTQ+ and BIPOC folks.

15. https://theluminaryarts.com/exhibitions/sick-time

For the Sick Time, Sleepy Time, Crip Time exhibition, Carolyn Lazard’s 12-hour durational performance, Support System (for Park, Tina, and Bob), 2016, features the artist laying in a bed for one-on-one visits, paid for with the price of a bouquet of flowers. The viewer becomes a participant in a one-on-one performance, done in the intimacy of the bedroom, centering the artist's need for rest and care. A place of convalescence becomes elevated as a temporal site for art. The documentation calls to mind an image that might be on a get-well-soon card, an arrangement of floral bouquets. I imagine Lazard might be speaking to the variations of societal regulations and expectations of how the sick body should look and act – the performativity of sickness. The performances of sickness range from the attempts to act well to make other people feel comfortable, the times one needs to perform pain to be taken seriously, to accusations of ‘faking’ and being ‘too dramatic.’ People who are chronically ill are often overlooked when their illness draws on, when their body refuses to get well. Society and loved ones move on without them. The performance and gesture of care has a timeline. A body (much like society) is expected to get back to normal after an accepted period of rest and recuperation.

Museums are sterile environments built for able-bodies, built to regulate bodies, or perhaps, not built for bodies at all.

Visitors are expected to respect the controlled sensorial environment in a museum. It is a regulated space, with social rules of conduct that require the body to adhere to ‘strict bodily discipline’ and order. These sites of surveillance demand no touching, no eating, no drinking, no talking or walking loudly. A place to display and flaunt the wealth of capitalist nations.16

![]()

![]() Shannon Finnegan, Do You Want Us Here or Not, 2018. MDO, paint, 72" x 26" x 36"

Shannon Finnegan, Do You Want Us Here or Not, 2018. MDO, paint, 72" x 26" x 36"

[TOP: A blue bench sits against a white wall, on the back of the bench in white text it reads: I’d rather be sitting. On the seat of the bench it reads: Sit here if you agree.

BOTTOM: A blue bench sits against a white wall, on the back of the bench in white text it reads:This exhibition has asked me to stand for too long. On the seat of the bench it reads: Sit here if you agree.]

Shannon Finnegan, Do You Want Us Here or Not, 2018. MDO, paint, 72" x 26" x 36"

Shannon Finnegan, Do You Want Us Here or Not, 2018. MDO, paint, 72" x 26" x 36"[TOP: A blue bench sits against a white wall, on the back of the bench in white text it reads: I’d rather be sitting. On the seat of the bench it reads: Sit here if you agree.

BOTTOM: A blue bench sits against a white wall, on the back of the bench in white text it reads:This exhibition has asked me to stand for too long. On the seat of the bench it reads: Sit here if you agree.]

16. Constance Classen and David Howes, “The Museum as Sensescape: Western Sensibilities and Indigenous Artifacts,” in Sensible objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture. edited by Elizabeth Edwards, Edith Anderson Feisner, and Ruth Phillips (New York: Berg, 2006).

The artist Shannon Finnegan simultaneously calls attention to the structure of the museum that excludes disabled bodies while offering solutions in the form of actual places for rest as benches and seating. The artwork functions as an intervention in spaces made for able bodies.17 Their series, Do you want us here or not,18 consists of blue wooden seating with phrases such as: "This museum has asked me to stand too long, sit here if you agree." and “It was hard to get here, rest if you agree.” These places to pause act as a subtle form of protest or refusal. Rest-refusal. When sitting upon their benches, the body is resting in solidarity.

17. Well, actually, all bodies require rest, more rest than the demands of capitalism allow.

18. Which is a great title, by the way.

18. Which is a great title, by the way.

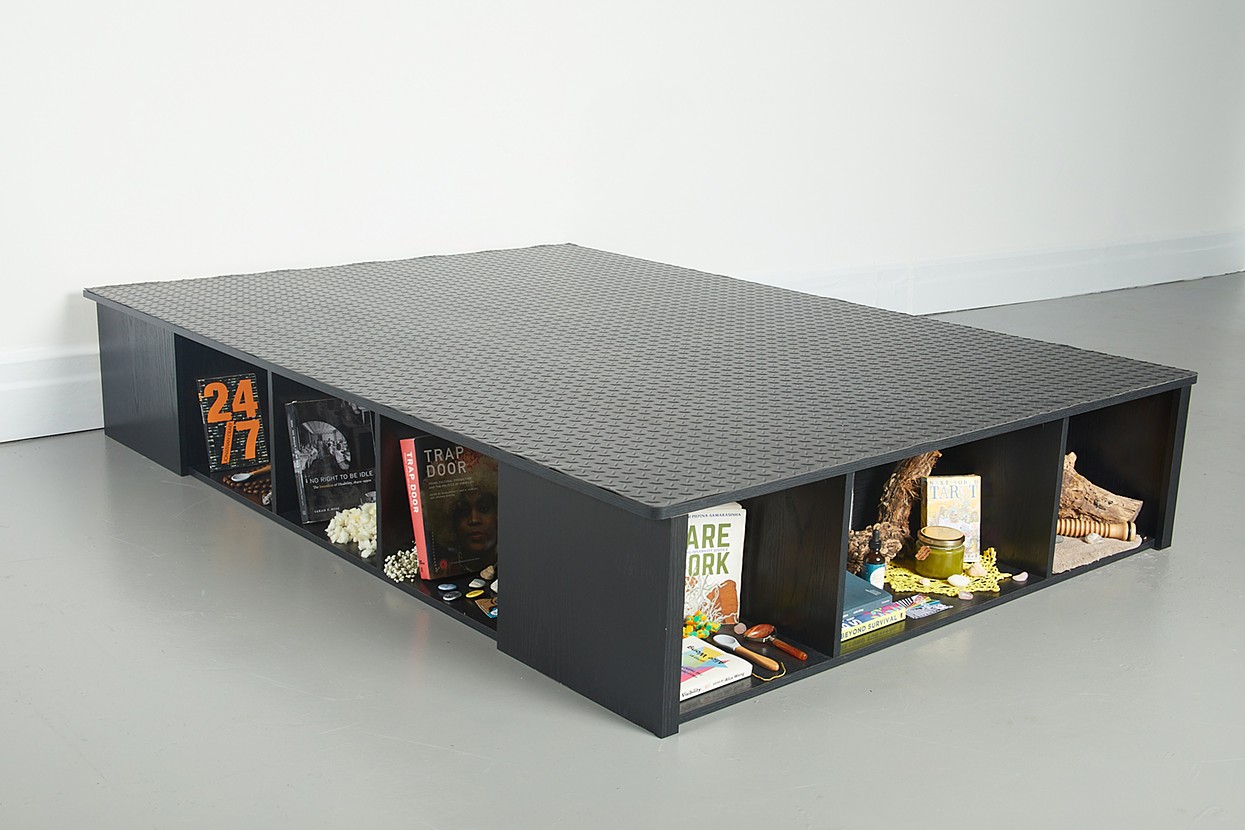

Alex Dolores Salerno, At Work (Grounding Tactics), 2020. Diamond Plate Rubber Flooring, Bedframe, Books, Stim Toys, Rocks, Wood, Candle, Hourglass, Tarot Cards, Heating Pad, Memory Foam, and Various Objects, 77" x 56" x 14". Image by Mike DiFeo

Alex Dolores Salerno, At Work (Grounding Tactics), 2020. Diamond Plate Rubber Flooring, Bedframe, Books, Stim Toys, Rocks, Wood, Candle, Hourglass, Tarot Cards, Heating Pad, Memory Foam, and Various Objects, 77" x 56" x 14". Image by Mike DiFeo[On a grey floor, against a white wall is a black bed frame shot at a 3/4th angle. The bed frame has built-in storage cubbies, 6 are visible. Inside of each cubby are various objects and ephemera, all intentionally placed, sculptures within the sculpture. Some of the objects that are visible include books (such as Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha and 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep by Jonathan Crary), rocks, a jar of salve, and the fuzzy surface of a heating pad. In the place of a bed is industrial black diamond plate rubber flooring cut precisely to the dimensions of the bed frame and laid flat across the surface. The diamond plate creates a textured patterned surface.] AltText courtesy of the artist's website.

Alex Dolores Salerno, At Work (Grounding Tactics), detail. Image by Mike DiFeo

Alex Dolores Salerno, At Work (Grounding Tactics), detail. Image by Mike DiFeo[TOP: This is a detail shot of At Work (Grounding Tactics) of the middle cubby on the side of the bed frame. Two books are propped up in a pile of shredded memory foam, Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure by Eli Clare and No Right to Be Idle: The Invention of Disability, 1840s–1930s by Sarah F. Rose. In the middle of the books is a small zine opened to a page that depicts exit signs and the word “laboratory”. In the front right are 2 stim toys, a black tangled interlocked toy and a red plastic mesh finger trap with an enclosed marble. Behind are two antique glass jars, one contains used bandaids and the other contains a prescription paper, a handwritten note with the word “Antioxidants” visible, and a sprig of a purple amaranth plant.] AltText courtesy of the artist's website.

BOTTOM: This is a detail shot of At Work (Grounding Tactics) of the middle cubby on the end of the bed frame. On the right side Next World Tarot by Cristy Road and a jar of green salve sit on a yellow fabric doily. Scattered in front are some small rocks and rose quartz. Next to them is an embroidered patch that depicts a rainbow emerging from black and white lines and reads “It’s time to dream think see act beyond prisons”, and tincture bottle that reads “ Love in times of crisis” On the right is the book Carceral Capitalism by Jackie Wang lying on top of Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement edited by Ejeris Dixon and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, and propped up behind them is Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds by Adrienne Maree Brown. In the back center is a long curvy piece of textured wood and a tall white candle.] AltText courtesy of the artist's website.

The artist Alex Dolores Salerno also creates sites of rest that refuse the regulation of bodies in public spaces and elevates rest’s importance. Their interactive sculpture, At Work (Grounding Tactics), is a bed as an art object. The bed offers the viewer a place to rest. When interacted with, the sculpture becomes an altar for the body and an altar for rest. There are cubbies around the bed filled with disability related objects and ephemera, such as books about rest and care, stim toys, and a heating pad. Each cubby is its own small altar to the crip body. The top of the bed is covered in a diamond plate rubber mat. The kind of industrial rubber mat used for non-slip surfaces, an essential implement for disability.

There is a long-standing historical precedent of excluding the disabled body from the protection of the many. Capitalism has trained society to fear the other, the poor, the disabled. The Ugly Laws were passed throughout the United States in the late nineteenth century marginalizing people with disabilities for fear that their difference- anything challenging the status quo - might be contagious and was dangerous to the state.

“In 1907, Alabama, for instance, passed laws prohibiting entrance into the state ‘of persons of an anarchistic tendency, of paupers, of persons suffering from contagious or communicative diseases, of cripples without means and unable to perform mental or physical service, of idiots, lunatics, persons of bad character, or of any persons who are likely to become a charge upon the charity of the State, and all such as will not make good and law-abiding citizens.’19

Marginalization is a historical norm. 20 But these beliefs didn’t grow out of Alabama; similar laws were established as early as 1867 (two years after the end of the Civil War) in San Francisco.21 These laws spread across the country, similar to how a disease might spread. Fear of disease spread, the disease of the contaminated other, which was believed to be caused by the immigrant, the poor, the mutilated, the maimed, and the disabled. Often based on aesthetic opinion that the disabled or “other” body was dirty, unclean, undesirable - abject.

[A group of pillowcases huddle together in a corner. They are stained from use and filled with medical ephemera from the artist and their friends, family and community. While removed from the bed, their form calls to mind the labor of rest and the collectivity of care. The obscured contents of the pillowcases negate the demand placed on pathologized subjects for a reveal, explanation or diagnosis. This opacity redirects us to view the forms as entities joined together in conversation and as a network of support. As a forever ongoing and growing work, the composition and number of pillowcases changes responding to the passage of time and installation site.] Alt-text courtesy of the artist.

Salerno’s work, Pillow Fight, consists of pillow cases that contain medical ephemera, forcing us to confront the abject body in the sterile space of the gallery. They are stained yellow from use, and are bulging at the bottoms, similar to the bulge of belly fat. Although the pillows invite one for rest, their filling suggests sharp edges that might cause pain if one rested on them. The stains also call to mind an intimacy and privacy of the bed and undergarments. The stains suggest the abject and ugly body, similar to the abject stigma of the visibly disabled body.

19. Susan Schweik, The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 168.

20. This thinking is still deeply ingrained in society, even now, as everyone jumps right “back to normal,” I am afraid and skeptical (as are many disabled people) of the CDC’s “Great Un-Masking” which feels reckless and premature. (We/humans are the test subjects.) There are still so many people who are vulnerable, even post-vaccine. The blatant eugenics tactics (sacrifice the weak, to save the economy) over the past 15 months for the comfort (unmasking) of the “healthy” (privileged, able-bodied) and capitalism (the economy) continues to further marginalize the disabled, leaving them behind and stuck at home, or dead. A study published in the UK revealed that 22,500 disabled people died due to COVID-19 between March and May 2020, compared with about 15,500 non-disabled people. https://www.disabilitynewsservice.com/coronavirus-call-for-inquiry-and-urgent-action-after-shocking-disability-death-stats/ Our society values the most fit, “healthy” individuals: the most productive. This valuing system deems disabled lives as unworthy. Eugenics, popularized in the late nineteenth century in the US and UK, (and later in Nazi Germany) is the eradication of “undesireables” through the forced sterilization and murder of mentally and physically disabled people (among other populations deemed ‘unfit’) who are believed to be a “burden on society”, and is still practiced today.

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/column-the-false-racist-theory-of-eugenics-once-ruled-science-lets-never-let-that-happen-again

https://www.newstatesman.com/society/2010/12/british-eugenics-disabled

21. Susan Schweik, The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 168

Capitalism says that disabled, tired bodies that spend too much time in bed are useless.

The disabled body subverts expectations about how a body should look, perform, and produce. The unstructured and horizontal resist the demands of neo-capitalism on the body. Pipzna-Samarasinha recognizes that “Capitalism says that disabled, tired bodies that spend too much time in bed are useless. Anyone who cannot labor to create wealth for owners is useless. People are valued only for the wealth they labor to build for capitalism; crips are useless to capitalism.” But she argues that liberation, organizing, and creating can happen in bed when one has the space and time to dream. Allowing our disabled bodies to reclaim time – to rest – provides alternate possibilities for survival.

Jillian Crochet is an interdisciplinary artist based in the Bay Area, working in sculpture, video, and performance, to confront grief and disability. Her practice seeks to liberate the disabled body from normalized marginalization and oppression. She is a current Graduate Fellow at Headlands Center for the Arts and a 2020 Artist in Residence at Art Beyond Sight’s Art & Disability program. She earned her BFA from the University of Alabama in 2007 and a MFA in Fine Arts from California College of the Arts in 2020.