The Queer Ecologies

of Liz Harvey

by Samantha Lyons

“What does it mean to have an embodied experience of plant-ness?”1

Fig. 1 the lost ones, Plan-d Gallery and the Los Angeles River, Los Angeles, CA, 2019

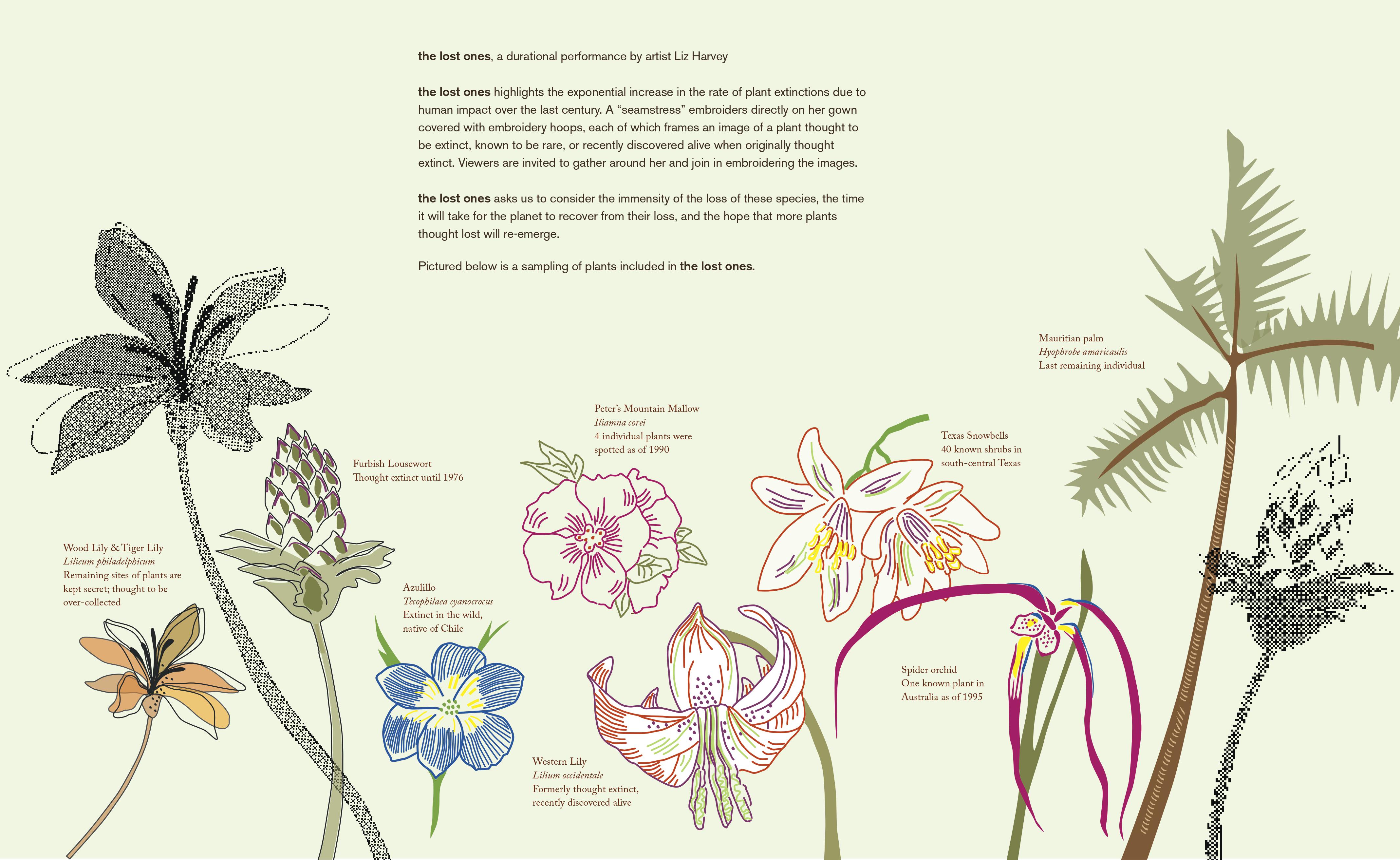

Since 2015, Bay Area artist Liz Harvey has explored this question in the lost ones, a series of collaborative performances that imagine perspectives and experiences of the non-human world through the human body. Informed by ecological concerns and feminist embroidery practices, Harvey’s performances involve a central performer who activates a communally stitched garment representing critically endangered plants. Harvey’s mesmerizing performances interweave environmentalism, embroidery, and dance to re-envision the body in public space and to engage audiences in meaningful embodied artmaking experiences. The ideas in these performances might best be understood and illuminated within the framework of queer ecology, a mode of ecocriticism that explores the disruption of boundaries such as human/non-human and natural/unnatural, as well as the precarious and liberatory implications of non-normative, boundary-crossing (and species-crossing) bodies in public environments.

Fig. 2- the lost ones, De Young Museum, San Francisco, CA, 2016

Over the course of eighteen different performances, the lost ones has evolved in its response to new sites and its inclusion of new audiences. What remains central to each performance is its participatory nature. Every performance has an interactive stitching circle component, developed in tandem with the sites, which range from urban parks and museums in San Francisco and San Jose to the concrete embankments of the Los Angeles River. Viewers become active participants during the performance and are invited to embroider vulnerable plant species on the garment while it is brought to life by the movements of different performers. In one iteration, Harvey’s collaborative performance with choreographer Mary Armentrout saw performers enact movements at the De Young Museum inspired by the concept of “plant time”—a perspective that, for the artist, embraces different temporalities and ways of being in the world. The performer led audiences through the galleries and outside the museum in slow movements inspired by non-human forms. For Harvey, there is an arresting quality to this unexpected deceleration, wherein people start to be more attentive to the small changes of their environment and to the human body. “When witnessing someone in plant time, there’s a visceral connection through witnessing it . . . There’s a certain power to that figure. She wields power. People follow her.” 2

Fig. 3 Marianne North (1830-1890), photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron

Fig. 4 Mary Seacole (1805-1881), photograph © Mary Evans Picture Library 2008

Fig. 4 Mary Seacole (1805-1881), photograph © Mary Evans Picture Library 2008

The slow-moving, spectral presence of Harvey’s performer emerges in part from Harvey’s fascination with the past. The conceptual origins of the lost ones is rooted in the histories of two 19th-century botanists and healers, Marianne North and Mary Seacole. North, an intrepid English botanist and botanical artist who left the domestic trappings of her Victorian life to travel the world independently, visited countries across the globe to record landscapes and plants in bold oil paintings. Seacole, a Jamaican-born healer and self-described doctress, frequently drew on plants in her medicinal practice, which she used both in Jamaica and later in her solo travels to Panama, England, and present-day Ukraine during the Crimean War.

Drawing a line between past and present, Harvey’s work connects these women’s stories and shared historical moment to some of the most urgent environmental issues of our times, including climate change and the human impact of pollution, deforestation and overpopulation on global plant and animal species. The garment’s surface traces the various colonized (or formerly colonized) nations both women traveled to by visualizing their native—and now critically vulnerable—plant populations. The flora embroidered on the garment represents a fraction of the endangered species on the IUCN Red List, distributed by the international conservation agency that monitors earth’s changing biosphere. Illustrating this alarming trend is a 2020 global report organized by the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, which states that around 40%—or two in five—of the world’s plant species are at risk of extinction.3 Another recent study concluded that nearly 600 plant species have become extinct since 1750, with the extinction of seed plants occurring at a faster rate than the normal turnover of species.4

Drawing a line between past and present, Harvey’s work connects these women’s stories and shared historical moment to some of the most urgent environmental issues of our times, including climate change and the human impact of pollution, deforestation and overpopulation on global plant and animal species. The garment’s surface traces the various colonized (or formerly colonized) nations both women traveled to by visualizing their native—and now critically vulnerable—plant populations. The flora embroidered on the garment represents a fraction of the endangered species on the IUCN Red List, distributed by the international conservation agency that monitors earth’s changing biosphere. Illustrating this alarming trend is a 2020 global report organized by the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, which states that around 40%—or two in five—of the world’s plant species are at risk of extinction.3 Another recent study concluded that nearly 600 plant species have become extinct since 1750, with the extinction of seed plants occurring at a faster rate than the normal turnover of species.4

Fig. 5 Card for the lost ones with endangered plant names, distributed by the artist between 2015-2016.

The rise of extinct and critically endangered species over the last century adds even greater urgency to the need to conserve plants and document plant extinctions, as Harvey does through her embroidered surfaces.

The threatened and extinct plants are stitched in individual embroidery hoops attached to the garment, inspired by a 19th-century wedding dress pattern of Seacole and North’s era. In the artist’s hands, this recognizable silhouette of the Victorian age is transformed into a disorienting and surreal form—a seamless depiction of the past disrupted by realities of the present, an unsettling reminder of industrialization’s deleterious effects on the natural world at the turn of the century and the thread that connects then and now.

Fig. 6 Skirt pattern with flowers created through community sewing circle events, San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles, San Jose, CA, 2018

In her performances, Harvey’s strange garments are set in motion through unconventional movements created in response to their respective sites.

Her collaborations with choreographers trained in dance styles that evolved from queer culture and non-Western traditions offer new ways to consider the body and its relationship to nature. For instance, past performances with choreographer Megan Nicely have included elements of Butoh, a style of avant-garde Japanese dance that explores the boundaries between natural and unnatural human movement. First performed in 1959 by Tatsumi Hijikata, who called the genre ankoku butoh (“dance of darkness”), Butoh has been noted for its queer themes as expressed through androgynous performers and unpredictable movements (its first performance was in fact inspired by Yukio Mishima’s novel Kinjiki, or Forbidding Colors, then a euphemism for homosexuality). Butoh’s experimental form and queering of movement is embraced by Harvey’s performers to a bizarre and uncanny effect in San Francisco’s well-populated and manicured urban spaces. In another iteration, choreographer Cherie Hill used the words of Mary Seacole as inspiration, speaking them aloud while activating Harvey’s garment through African dance traditions that incorporated sweeping, space-taking movements. Hill’s animation of Victorian-inspired clothing provided further ways to assess the complex colonial histories of Seacole and North’s time with the racial issues of our own.

Fig. 7 the lost ones: bodies of knowledge, with Cherie Hill performing at Salesforce Park, San Francisco, CA, 2018

For Harvey, both Seacole and North were compelling historical figures for their interest in the natural world and for their disruption of conventional notions of femininity and normative choices for women at the time. 5 While not queer per se in the historical record, they were women ahead of their time, or out of time. The same might be said of Harvey’s creation. In her own words, the “queer creature that takes up residence in the garment is a cross-species creature: part woman, part plant, part flower.”6 In a strategy aligned with queer ecological thinking, Harvey’s performances not only ask the viewer to rethink the binaries of gendered bodies, but also the boundaries between human and non-human worlds.

Fig. 8 the lost ones, with Megan Nicely performing at Yerba Buena Night, Jessie Square, San Francisco, CA, 2019

Queer ecology, a mode of ecocriticism that operates at the intersection of LGBTQ and environmental politics, draws upon queer theory’s challenge to gender- and sex-based hierarchies and applies this approach to ecological and evolutionary thinking.

Scholars Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson describe the aim of queer ecological studies in the following way:

Specifically, the task of a queer ecology is to probe the intersections of sex and nature with an eye to developing a sexual politics that more clearly includes considerations of the natural world and its biosocial constitution, and an environmental politics that demonstrates an understanding of the ways in which sexual relations organize and influence both the material world of nature and our perceptions, experiences, and constitutions of that world.7

Such an approach shines an important light on not only the heteronormative scientific bias in ecological studies, but also in religious and political discourse, as the concept of “nature” has long been used to devalue queerness (and thereby validate heterosexuality by centralizing male-female practices of sexual reproduction).8

Yet as many evolutionary biologists have noted, nature is a vastly diverse realm. We are only recently gaining a better understanding of the widely underreported status of sexual biodiversity in the plant and animal world. As Joan Roughgarden points out in her essential study Evolution’s Rainbow: Diversity, Gender and Sexuality in Nature and People, the most common body form among plants (and in a large portion of the animal kingdom) is for an individual to be both male and female at the same, or at different times of its life.9

The diversity of gender and sexual expression in plants acts as a liberatory framework to approach the human body, as it allows one to question the naturalness and stability of established categories of gender, sex, and sexuality. Plants’ unfixed nature—their ability to transform—is part of what draws Harvey to them as naturally queer.

Fig. 9 Stitching circle as part of Plan-d Gallery performance, Los Angeles, CA, 2019

If Harvey finds connections between the biodiversity of the non-human world and the broad spectrum of sexual identities and gender expressions in the human one, her work also notes their shared position of vulnerability. She relates:

The perspective of the plant that is leaving its environment and won’t survive in its habitat anymore—taking that perspective is like a view from the edge of something. It’s a submerged kind of view. There’s a queerness there to me. And plants feel like they’re near the bottom of the hierarchy. Things in nature transform and they also are temporary.10

Her work notes the common precarious ground that exists between endangered plants and queer bodies—the former by climate change, deforestation, habitat loss and pollution—the latter by issues of visibility, safety, and the fraught navigation of public spaces. In the United States, the alarming rise of state proposals to exclude access to public bathrooms for trans individuals who do not contort to conventional presentations of gender is especially poignant.

Fig. 10 the lost ones, Yerba Buena Night, San Francisco, CA, 2015

Although the social issues these performances engage with are among the most immediate of our times, the work’s embrace of “plant time” emphasizes an approach that is deliberately measured and meditative. For the artist, this slowing down is an important way to bring other non-human points of view into focus. This is one of the central conceptual aims of the stitching circles, as participants in each of the performances are invited to take part in the steady, ritualistic act of sewing. With its emphasis on measured handwork, these circles enact a deceleration of time and immediacy through unhurried forms of making.

Fig. 11 the lost ones stitching circle, San Francisco, 2018, with science editor Lauren Muscatine (pictured far left) in conversation with participants about climate change and the healing power of plants. Muscatine collaborated with Harvey in engaging stitchers in conversation for two performances.

The stitching circles naturally invoke a conversation about time and the changing perspectives on human and non-human forms of creation. Her garments, carefully constructed through handwork traditions, use sewing and embroidery—skills historically defined and marginalized as women’s work (Roszika Parker’s line, “When women embroider, it is seen not as art, but entirely as the expression of femininity” comes to mind).11 The use of sewing and textiles invoke long-standing histories of artistic hierarchies and gendered associations. However, in Harvey’s hands, the use of sewing creates a flexibility of the medium at odds with traditional understandings too frequently rooted in definitions of sexual difference. Harvey turns the anachronistic elements present in her performance on their head, disrupting the naturalness of needlework and femininity cemented in the Victorian age within the context of rigidly defined sex roles in her hybrid forms. The very materials Harvey uses may also be read as queering artistic production for their flexible structure and expansive range of meanings. This kind of indeterminacy is noted by Julia Bryan-Wilson, who comments on “the instability of textiles’ relationality, which in some instances might be felt to be queer—that is, how they propose different sorts of bodily orientations and create volatile interfaces between public and private selves.” 12

If Harvey’s works propose a slowing down of time in the present, her work also plays with historical time through her invocation of Mary Seacole and Marianne North’s stories. This non-linear temporality presents a kind of queer time, a looping between past and present, with detours into imagined futures.13 Pulling the spirits of these two women out of their time and into ours, they become modern-day Cassandra figures, the cursed prophetess, transforming the pastoral and decorative flower motifs of traditional embroidery fused to her body into portraits of mourning for our natural world.

“The plants want you to listen to them. That may be the key thing that is needed, to listen to other perspectives. Plants have other perspectives. If plants are speaking to us, what are they trying to say?” 14

This

listening

and perspective sharing takes place in the communal social spaces of

Harvey’s sewing circles, where participants can actively take part in

creating these portraits of remembrance. The result is a deeply

collaborative act of making. The variety of flowers and

their varying level of finish is a testament to the broad group of

people who participate, from skilled artists to enthusiastic

children—some of the embroidered plants are done precisely, others

imperfectly, with tangles of thread and loose ends. The conversations

that develop within these stitching circles on the topic of climate change and loss are each unique,

sprawling, and personal. Science

editor Lauren Muscatine joined Harvey for several of these sewing circles between 2018 and 2019, including performances

in San Francisco with Cherie Hill and in Cotati (Sonoma County) with Megan Nicely, to

lead dialogues with participants about the way plants are responding to the changing climate. In

one of these circles,

a participant

can be heard reflecting on the changing environment in her own

neighborhood: “Things that used to dieback [after a freeze] don’t

dieback anymore. But also things that used to grow don’t grow anymore.”

Fig. 12 the lost ones, with Megan Hertzel, San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles, San Jose, CA, 2018

For the artist, the task of changing dynamics between people and between people and their environments takes both time and care. She writes:

Relationships between people take time to build; it's something that can't be rushed, and how that can be said of relationships between people and nature—and in the case of my piece, people and plants….it’s when the relationships have been built that we can call people to take urgent action when there is a crisis, and they will respond because there's a connection to the heart.15

By inviting viewers to reimagine their relationship with the non-human world, her work proposes an expanded consideration of what is deemed “natural” and a new perspective of plant life alongside queer ways of being—a position of radical empathy that grows essential connections for social and ecological change.

Relationships between people take time to build; it's something that can't be rushed, and how that can be said of relationships between people and nature—and in the case of my piece, people and plants….it’s when the relationships have been built that we can call people to take urgent action when there is a crisis, and they will respond because there's a connection to the heart.15

By inviting viewers to reimagine their relationship with the non-human world, her work proposes an expanded consideration of what is deemed “natural” and a new perspective of plant life alongside queer ways of being—a position of radical empathy that grows essential connections for social and ecological change.

Samantha Lyons is a Bay Area-based art historian and curator. She received her MA and PhD from the University of Kansas and has held curatorial positions and internships at the Spencer Museum of Art and Institute of Contemporary Art San Jose. She currently works as Assistant Curator at the San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles in San Jose, CA.

Liz Harvey was an Artist in Residence at SJMQT in Spring 2018. Her permanent collection work, Whisk, will be part of the San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles 45th Anniversary exhibition, scheduled for January 12 - April 3, 2022. The work is part of their permanent collection. Harvey will also host a stitching circle at SJMQT in conjunction with the exhibition Queer Threads (April 13 - July 3, 2022), guest curated by John Chaich, in Summer 2022.

Liz Harvey was an Artist in Residence at SJMQT in Spring 2018. Her permanent collection work, Whisk, will be part of the San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles 45th Anniversary exhibition, scheduled for January 12 - April 3, 2022. The work is part of their permanent collection. Harvey will also host a stitching circle at SJMQT in conjunction with the exhibition Queer Threads (April 13 - July 3, 2022), guest curated by John Chaich, in Summer 2022.

1

This quote comes from an interview with the artist on May 3, 2021. I am thankful to Liz for her time and generosity in sharing details about her work. Unless explicitly mentioned, all quotes from this article derive from this interview.

2

Interview with the artist, May 3, 2021.

3

Damian Carrington, “40% of world’s plant species at risk of extinction,” The Guardian, September 29, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/sep/30/world-plant-species-risk-extinction-fungi-earth. For more on Kew’s State of the World’s Plants and Fungi project, visit their website: https://www.kew.org/science/state-of-the-worlds-plants-and-fungi.

4

Aelys M. Humphreys, Rafaël Govaerts, Sarah Z. Ficinski, Eimear Nic Lughadha and Maria S. Vorontsova, “Global dataset shows geography and life form predict modern plant extinction and rediscovery,” Nature Ecology & Evolution 3 (July 2019): 1043. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0906-2.

5

Both women also notably wrote and published memoirs, which chronicle their travels and life pursuits. See Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands (London: James Blackwood, 1857) and Recollections of a Happy Life: Being the Autobiography of Marianne North (London: Macmillan and Co., 1892).

6

Liz Harvey, “the lost ones,” http://www.lizharveystudio.com/artworks. Accessed April 29, 2021.

7

Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson, “Introduction: A Genealogy of Queer Ecologies,” in Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 5.

8

The same terms used to characterize disruptive environmental events or crises—pathological, contaminated, diseased and so on—are often the same terms conventionally used to invalidate queer people as acting or being against nature. Nicole Seymour, Strange Natures: Futurity, Empathy, and the Queer Ecological Imagination (Urbana: University of Illinois Press), 19.

9

Joan Roughgarden, Evolution’s Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 27.

10

Interview with the artist, May 3, 2021.

11

Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, rev. ed. (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2019), 5.

12

Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art and Textile Politics (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017), 29.

13

Bryan-Wilson, 262. Her reference to queer time builds upon the theoretical writings of Elizabeth Freeman, who explores this concept in her introduction to Queer Temporalities, a special issue of GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 13, nos. 2-3 (2007): 159-176 and in Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010).

14

Interview with the artist, May 3, 2021.

15

Email correspondence with the artist, May 6, 2021.