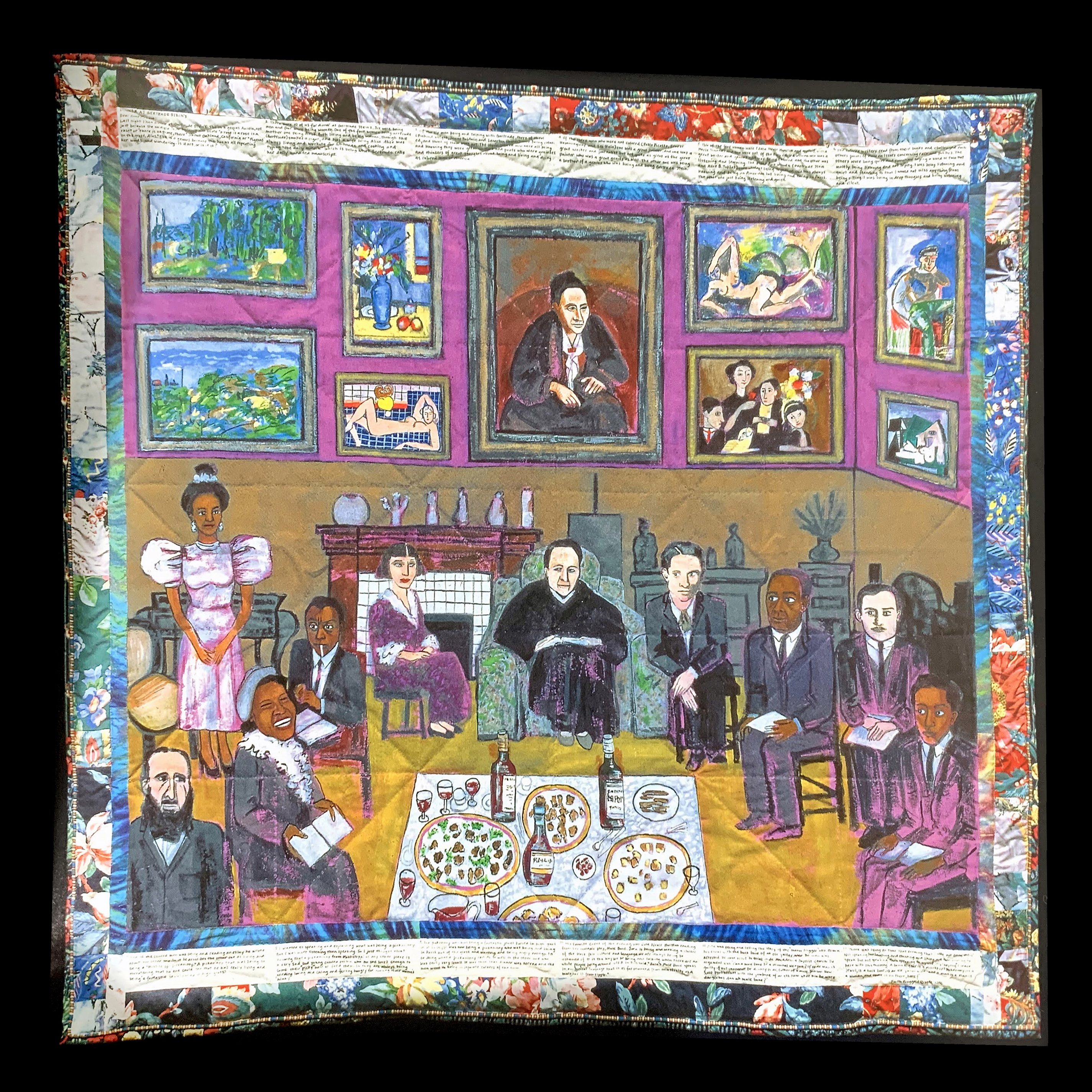

Figure 2. Seated from left to right: Leo Stein, Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, Langston Hughes, Ernest Hemingway, and Richard Wright. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Read in Stitches:

Faith Ringgold’s Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s

Kira Dominguez Hultgren

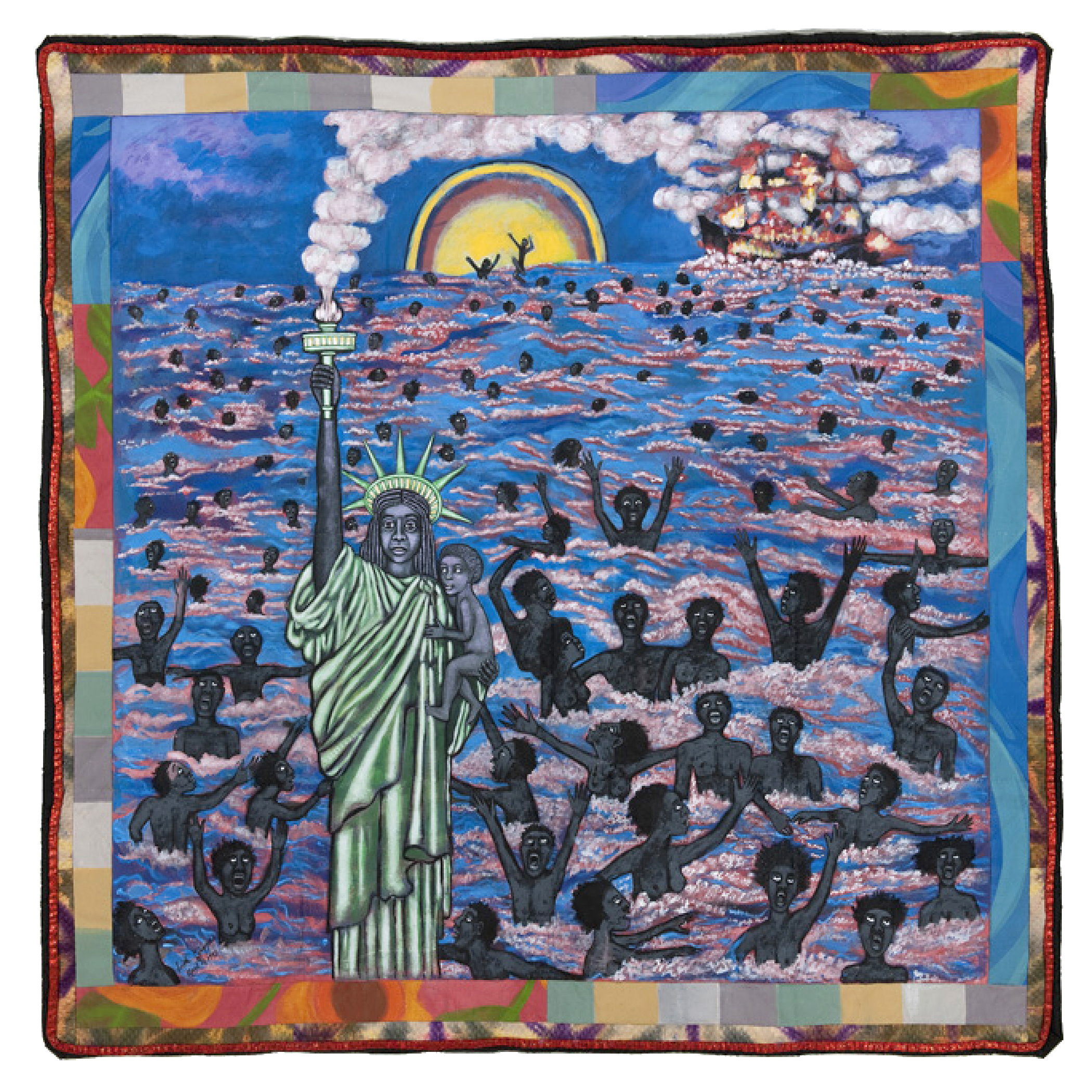

Faith Ringgold (b. 1930, Harlem, NY) is a painter and writer. And yet, she is known for her story quilts–painted, written, and stitched compositions that document, memorialize, narrate, and (re)imagine histories, particularly the histories of Black women in America. (Fig. 1)

Left: Fig. 1: Faith Ringgold, Slave Rape Story Quilt, 1985, Tie-dyed and printed cotton fabrics and ink on cotton fabric sewn over polyester fiber batting, 82” x 73.” Newark Museum, http://gallery.newarkmuseum.org/view/objects/asitem/items$0040:2962116

In relying on the structure of a quilt, on painted, written, and stitched compositions being mediated through one another, Ringgold marks out both metaphorically and visibly how intersecting positions of difference creates new spaces from which history can be made and remade. Take for example her 1991 story quilt, Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s (Fig. 2). In this piece, racial, gender, and queer intersectionality meet a communicative and artistic pluralism, where painting, storytelling, and quilting are inextricably slipping into, holding up, and negating one another to tell a more nuanced story than any one medium can do on its own.

Seated in the middle of this painting is Gertrude Stein, a queer American modernist icon, art collector, and writer. Stein was known for her weekly salons in Paris in the early 1900s, where international artists and authors gathered to see her precursor to a modern-art-museum-salon. In this painting, Ringgold reimagines Stein’s salon. Seated from left to right, we find Leo Stein (Stein’s brother), Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, Alice B. Toklas (Stein’s wife), Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, Langston Hughes, Ernest Hemingway, and Richard Wright. In other words, interspersed into this gathering, positioned in-between those who history tells us knew Stein and frequented her salons (i.e. Leo Stein, Toklas, Picasso, and Hemingway) is a well-known canon of African-American modernist writers. When asked about this work, Ringgold said, “my process is designed to give us ‘colored folk’ and women a taste of the American Dream straight up. Since the facts don’t do that too often, I decided to make it up…”1 Yet, it is important to note that Ringgold is not reacting to exclusion, or the desire to be included in Stein’s salon, so much as visualizing a parallel-universe or history where a diverse group of black writers across time tell their own story, sitting like Stein in positions of marked difference and significance to one another and the viewer.2

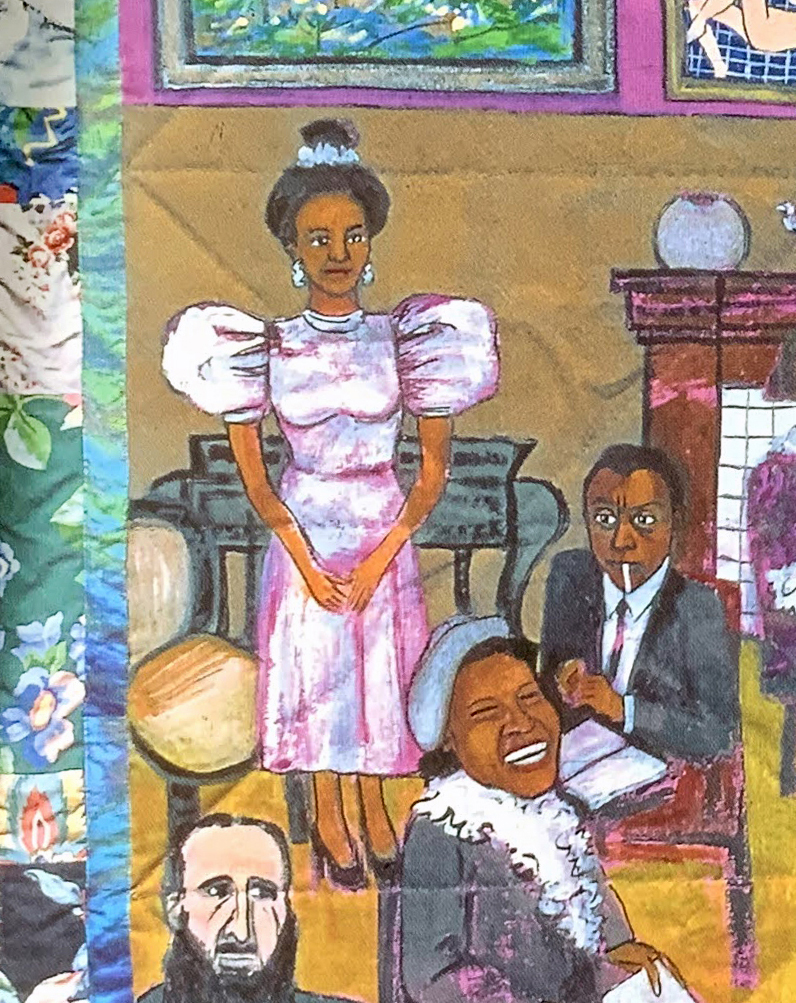

Fig. 3: Willia Marie Simone, a fictitious young black artist who has come to Paris to study and make art.

Detail. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

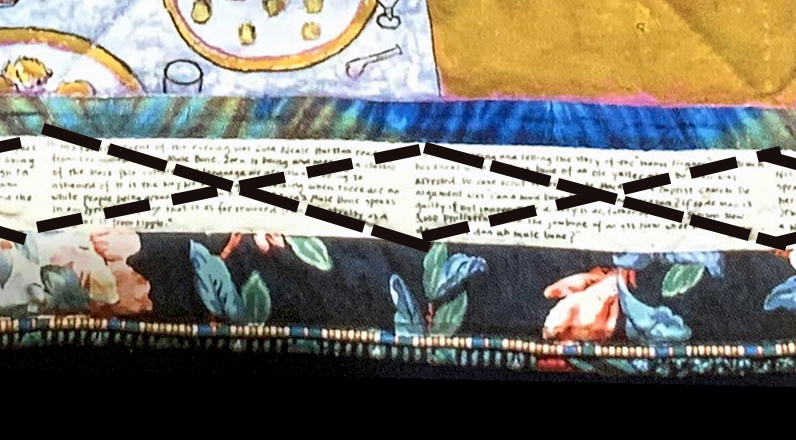

Detail. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Fig. 4: Black lines digitally overlaid onto these two text panels show how the stitching makes an X-mark over each of Simone’s letters.

Digital Overlay. Detail. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Digital Overlay. Detail. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Ringgold does not just reimagine Stein’s salon through painting, but also through a narrated story about the gathering read in the letters which border the tableau. Standing in the pink dress just outside the half-circle of seated figures is Willia Marie Simone, a fictitious young black artist who has come to Paris to study and make art (Fig. 3). She sends letters to her Aunt Melissa living in the U.S. that recount her experiences in Paris written into the top and bottom of the quilt. As a character, she guides the reader through each of Ringgold’s twelve story quilts that make up The French Collection, in which Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s is ninth. Simone is semi-autobiographical, a pieced together representation who embodies not just Ringgold’s experiences and desires, but also Ringgold’s mother, Willi Posey, and Ringgold’s daughter, Michele Wallace’s experiences and desires.3 Through these letters, we learn that Simone is silent throughout the gathering, wanting to share her opinion, but again and again writing to her aunt, “being listening and quiet.” 4 The X marked in stitches over top each of these letters further emphasizes Simone’s presence and silence (Fig. 4). Simone has her say – materialized and written for her aunt and the viewer – but it is also visibly negated, an X marking and refusing each one.

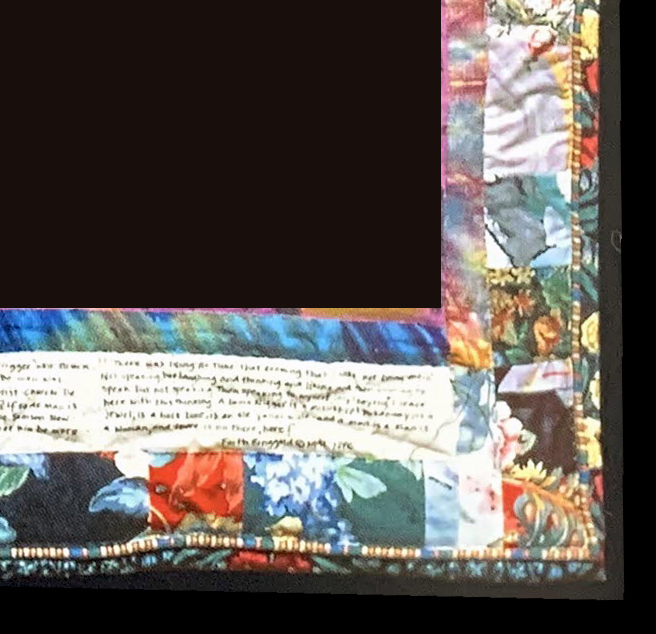

Fig 5. The pieces of fabric are stitched together to form nearly invisible seams around the border.

Detail. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Detail. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Fig. 6:

The border is not sewn to the backing of the quilt. Because of this, the Xs over each written tile of fabric create a deeper depression into the batting, and stand out more sharply.

Detail. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Fig. 7:

White and black lines are digitally overlaid onto the work to show the quilted stitch lines.

Digital Overlay. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

It is not just through painting and writing that Ringgold mobilizes intersectional positionality to reimagine parallel-histories (Black modernist authors), and yet-to-be-seen audiences and the next generation of artists (Simone), but it is also through stitching. Before following these lines of stitches farther, it is important to distinguish the two different kinds of stitching that happen in Ringgold’s quilts. First there is the piece-work, where two pieces of fabric are held together through stitching that becomes visually recognizable as a seam. This kind of stitch work is only found at the borders of Ringgold’s piece (Fig. 5). This border is not quilted in her work, meaning that stitched-together pieces float on top of the batting and backing fabric to form one continuous frame around the central quilted piece (Fig. 6). This border or frame around the work points to the position of this piece hung at right angles in the white-cube of the gallery, as well as to the rules of binding and finishing in the language of quilting. The second kind of stitch found in Ringgold’s work is the quilted running stitch. This stitch, seen atop Simone’s letters and the painted tableau in the middle, hold the written and painted canvas to the batting and backing fabric (Fig. 7). This stitch is visible and becomes visually significant to the composition. Our eyes can follow and trace these lines easily, such as the Xs over Simone’s writing (Fig. 4). These rows of crossed-out writing form a second border or narrative-frame embedded into the first, hemming in the painted tableau on top and bottom.

Fig. 8: The imagined audience seen as a digital overlay stands in front of Ringgold’s work, completing the circle of seated guests around the table.

Digital Overlay. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

While the first narrative frame, the border, speaks to the position of this piece in the gallery and within the language of quilting, the second embedded-narrative frame, Simone’s letters, speaks to the dual-audience Ringgold makes present in this work. First there is the audience in the position of Aunt Melissa, whose history, whose lineage, is in line with Simone’s. Second there is the viewer, who gazes at the painting, who reads the letters addressed to someone else, and who follows the lines of stitches. The assumed-spectator forms the other half of the semi-circle in the tableau (Fig. 8). How these two audiences work together and against one another is, in part, what is at stake in the reading of the stitches in this piece.

To follow the lines of stitching over the painted tableau is to understand who is being pointed to and who is being reflected.

Fig. 9: The stitching at each corner crosses directly over both Stein’s person and portrait. The stitching also encloses the seated group while visibly drawing a line between them and Simone. Digital Overlay. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Fig. 10: The central lines of stitching extend beyond the seated guess to point at Simone. Digital Overlay. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Fig. 11: These digital overlaid lines below the quilt imagine who else is standing outside the seated circle in Simone’s position. Digital Overlay. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

To follow the lines of stitching over the painted tableau is to understand who is being pointed to and who is being reflected Compositionally and materially, Stein is at the center of this piece. The two rows of stitching beginning at the bottom right and left corners of the quilt cross directly over both her person and portrait hung on the wall (Fig. 9). These two rows of stitching also near-perfectly enclose the half-circle of guests around Stein, leaving Simone visibly excluded not just because she is standing, but because of the line of stitches that divide her from the group. Yet, consider the two lines of stitches that begin in the bottom center of the tableau - arguably what is the true center of the quilt since only half of both the gathered group and table setting is seen from this point upward. These two lines point out past the circle of Stein and her guests (Fig. 10). One of these lines points to and crosses directly over Simone. The other line skirts neatly between the heads of Hughes and Hemingway to point to no one within the frame of the painting/quilt. These two lines of stitches make me wonder who else is standing outside the circle, not just looking in, but directly pointed at as the carriers of the legacy and the story of this gathering (Fig. 11).

Fig. 12: These digital overlaid lines fall at the compositional middle of the quilt. Digital Overlay. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Fig. 13: The paintings on the wall reflect the seated gathering, the seated gathering reflects the viewership. Digital Overlay. Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein's (The French Collection, Part II: #9), 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 79" x 84." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

There are two ways to think about the method Ringgold uses to carry this legacy forward. First, it is carried forward in artwork. Ringgold’s painted composition reflects the seated gathering back onto the walls. Stein is both present and painted. Picasso is present and his paintings are hung above his head. Secondly, the legacy is carried forward in the viewer. The composition of the stitched lines on top of the tableau are unresolved. If the center of the quilt from right to left is at the point that meets in the center of the table, then the measurable middle of the quilt from top to bottom, is not actually marked out in stitches at all. It would roughly fall at the top of Stein’s head. Textile scholar Jessica Hemmings claims in her summer 2020 article in Parse Journal, That’s Not Your Story: Faith Ringgold Publishing on Cloth, that this unbalanced composition is an aesthetic choice, “a stylistic trait that runs throughout Ringgold’s work with cloth.”5 But this stylistic trait, whether intended or not, changes what is seen as the middle of the quilt from a compositional standpoint. The middle falls over Stein’s person (Fig. 12). A whole section of this tableau is imagined, pointed to, but not actually depicted. Is it an imagined audience on whom Ringgold relies that finishes this circle of intellectuals? If the viewer is being imagined–not just in this piece, but in Ringgold’s French Collection as a whole–the stitch work in the collection is also compositionally unresolved, and also pointing similarly outward, Ringgold is making an alternative (i.e. not part of the canon) art history that reflects an alternative (i.e. not the average museum-goer) viewership, an audience who sees this gathering in a Parisian salon and claims it as their own (Fig. 13).

Fig. 14: The white stitching is visible in many parts of this work. Detail. Faith Ringgold, Picasso’s Studio, 1991, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 73" x 68." Photo Credit: Gamma One.

To understand the who and why of this alternative audience, this imagined viewer, first let’s look at its reflection, the alternative art history being depicted.

Zora Neale Hurston, seated second from the far-left, draws everyone’s side-eye gaze in the painting, except for Toklas, who only has eyes for Stein. Hurston’s body becomes the proverbial open book painted on her lap: her head thrown back, her lips open, her eyes closed, turned inward. Her laughter displaces every other narrative in the room. She’s not trying to fit in at all, as she enjoys a joke that no one else wants to share with her.

It is not surprising then when we read Simone’s letters, that Simone adopts not just Stein’s style of language, but Hurston’s style as well. In her article, ‘We Can Make It Come True’: Faith Ringgold’s Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s, Tirza True Latimer explores this slippage in Simone’s language, writing “this textual transaction (entwining Stein and Hurston in a literary kinship) should be understood as equivalent to the quilt painting's visual gambit of interspersing black cultural innovators among Stein's privileged guests.”6 This slippage of syntactic styles does not just correspond to the collision of expected and unexpected guests in Stein’s salon, however. It is a slippage that Ringgold herself embodies as she moves between painting, writing, and stitching; and like Simone’s narrative letters, it is impossible to extract meaning by only paying attention to one style.

When trying to uncover the order in which Ringgold constructed these story quilts–painting and then stitching or stitching and then painting–it quickly became clear that she moves between both mediums throughout the process. In some quilts, such as Picasso’s Studio (1991), the stitches are white, a strong, visible color contrast to the punctured painted canvas behind it, while in other quilts, such as Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s, the stitches look as though they were painted over (Fig. 14). As closely as I can determine it, Ringgold began this quilt with a painted solid color canvas (the magenta color seen on the walls of Stein’s salon), which was pieced to the floral and text border. She then painted the tableau on the magenta canvas, marked out the stitches, sewed it, and then went back over those stitches again in paint.

While the order is perhaps significant, the position of each technique or expression lined up next to the other is what allows Ringgold to mobilize and slip between the narrative variability of all three, materializing yet another parallel history, her own family’s history of quilting, dressmaking, and factory sewing. She writes in her autobiography about her choice to become an artist, “I felt I had something to add–the visual depiction of the way we are and look.”7 Ringgold was born into a working-class family. Her mother owned her own clothing business for a time.8 Her childhood was not marked by the victimization or suffering which many expected her to express as a Black woman. Sewing in Ringgold’s home was not reduced only to the history of subjugation. Like Hurston, made strange with her laughter in Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s, or Simone, made strange through her in-between language, Ringgold’s use of quilting is not a monolithic stand-in for black material culture. Rather it becomes a narrative tool, its meaning variable according to context and use, just like any form of expression.

The narrative variability of the stitching is key to identifying the audience that is being reflected in this painting. On the one hand, it is an audience like Simone, young Black women artists trying to find a role model, someone with whom they are in line, and with whom they are in conversation.9 Throughout her career Ringgold has been an educator-activist, committed to giving the next generation of black artists a history that reflects them, and their experiences. She says, “when you can see yourself in the development of a culture, you can do it too.”10 In choosing to paint and write on a quilt, she makes certain that both so-called high and low-art forms and histories are equally valid and intersecting narrative choices for this next generation, perhaps even insisting that to occupy a position of difference is to always work in-between expressed divisions.

The narrative variability of the stitching is key to identifying the audience that is being reflected in this painting. On the one hand, it is an audience like Simone, young Black women artists trying to find a role model, someone with whom they are in line, and with whom they are in conversation.9 Throughout her career Ringgold has been an educator-activist, committed to giving the next generation of black artists a history that reflects them, and their experiences. She says, “when you can see yourself in the development of a culture, you can do it too.”10 In choosing to paint and write on a quilt, she makes certain that both so-called high and low-art forms and histories are equally valid and intersecting narrative choices for this next generation, perhaps even insisting that to occupy a position of difference is to always work in-between expressed divisions.

Fig. 15: Faith Ringgold, We Came to America (The American Collection: #1), 1997, Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, 74 ½” x 79 ½.” Photo Credit: Gamma One.

Fig. 16: Faith Ringgold, The Flag is Bleeding #2 (The American Collection: #6), 1997, Acrylic on canvas, painted and pieced border, 76” x 79.” Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, https://www.houldsworth.co.uk/artists/73-faith-ringgold/works/9678-faith-ringgold-the-flag-is-bleeding-2-american-collection-6/

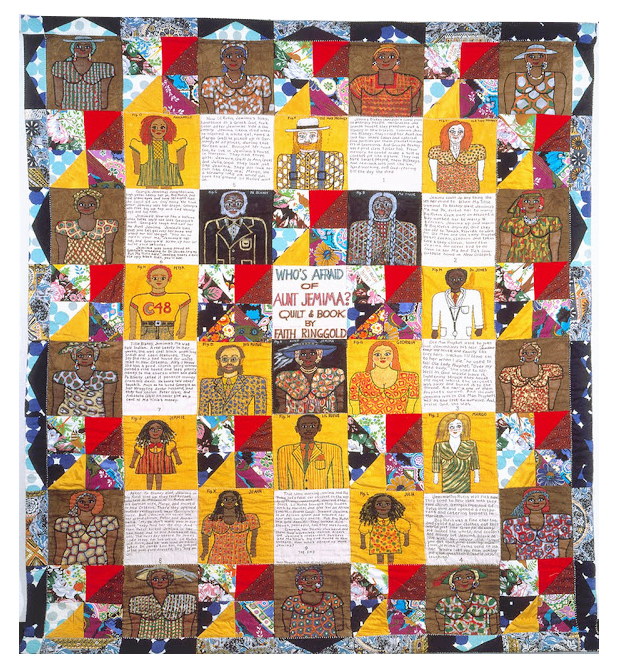

Fig. 17: Faith Ringgold, Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima, 1983, Acrylic on canvas, dyed, painted and pieced fabric, 90” x 80.” Photo Credit: Studio Museum in Harlem, NY

Yet this is only one part of the audience who gazes at this quilt. Interspersed into this next generation of black artists, are those who would be made uncomfortable by the scenes Ringgold chooses to paint and write about, particularly scenes of historic and ongoing violence perpetrated on the black body (Fig. 1, 15-16). Ringgold uses quilting to soften the blow for this audience who otherwise might look away. When speaking about her work, Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima (1983), Ringgold explained “Everyone knows what a quilt is…I made people accept my work much better than before I started making the quilts”11 (Fig. 17). Textile scholar Julia Bryan-Wilson similarly explains about the effects that a quilt can have on a viewer’s reading when speaking about the NAMES Project AIDS quilt, pointing out that quilts have the ability to humanize experiences that otherwise would not be relatable.12 Everybody knows what fabric feels like on the body. Even if the mind refuses to accept the visual, through fabric, the visual becomes inescapably known to the body of the viewer.

In this sense, Ringgold’s stitch becomes a kind of punchline throughout her paintings. What can’t be heard straight, can be heard with a slantwise punchline behind it, softening the reception, sometimes outright negating it visually; remember the crosses that are stitched over top each of Simone’s letters (Fig. 4). Although the tableau in Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s and the French Collection as a whole are not as overtly troubling as some of her other works, Ringgold nonetheless is critiquing narratives that elide not just black experience and history, but queer and intersectional experiences and history. The audience she points to and assembles around this table is made to look again, to acknowledge where their vision, their history, and their education is limited; how it is only one way of seeing, one way of knowing, one way of saying, and one way of making.

The stitches in Ringgold’s story quilts do a lot of work. Through the stitches, and through her story quilts, Ringgold points to those outside the circle like Simone, who are looking and finding role models. She also points to those forming the remainder of the seated semi-circle who perhaps can more easily identify Picasso’s painting than Hurston’s writing; and for this imagined dual-audience, Ringgold paints, writes, and stitches competing and interspersed vernaculars, creating in-between art out of intersectional life experience (Fig. 18). Here is the humdinger, Ringgold doesn’t actually stitch any of these quilts.13 She is a painter and writer.

In this sense, Ringgold’s stitch becomes a kind of punchline throughout her paintings. What can’t be heard straight, can be heard with a slantwise punchline behind it, softening the reception, sometimes outright negating it visually; remember the crosses that are stitched over top each of Simone’s letters (Fig. 4). Although the tableau in Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s and the French Collection as a whole are not as overtly troubling as some of her other works, Ringgold nonetheless is critiquing narratives that elide not just black experience and history, but queer and intersectional experiences and history. The audience she points to and assembles around this table is made to look again, to acknowledge where their vision, their history, and their education is limited; how it is only one way of seeing, one way of knowing, one way of saying, and one way of making.

The stitches in Ringgold’s story quilts do a lot of work. Through the stitches, and through her story quilts, Ringgold points to those outside the circle like Simone, who are looking and finding role models. She also points to those forming the remainder of the seated semi-circle who perhaps can more easily identify Picasso’s painting than Hurston’s writing; and for this imagined dual-audience, Ringgold paints, writes, and stitches competing and interspersed vernaculars, creating in-between art out of intersectional life experience (Fig. 18). Here is the humdinger, Ringgold doesn’t actually stitch any of these quilts.13 She is a painter and writer.

Fig. 18: Image of Ringgold sewing Echoes of Harlem, 1980, with her mother Willi Posey. Screen shot from Craft in America, “THREADS Episode,” PBS, May 11, 2012. Video, 53:25. https://www.pbs.org/video/craft-in-america-episode-viii-threads/

1

Moira Roth, “Of Cotton and Sunflower Fields: The Makings of The French and The American Collection,” in Dancing at the Louvre: Faith Ringgold's French Collection and Other Story Quilts, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 60.

2

“It raises questions about how figures of difference operate (differently) when introduced into orthodox narratives of cultural creation,” Tirza True Latimer, “‘We Can Make It Come True’: Faith Ringgold’s Dinner At Gertrude Stein’s,” English Language Notes 51, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2013): 132.

3

Michele Wallace, “The French Collection: Momma Jones, Mommy Fay, and Me,” in Dancing at the Louvre: Faith Ringgold's French Collection and Other Story Quilts, 18.

4

Faith Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s, transcription of quilt story appears in Dancing at the Louvre: Faith Ringgold's French Collection and Other Story Quilts, Dan Cameron, et al., (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 139.

5

Jessica Hemmings, “That’s Not Your Story: Faith Ringgold Publishing on Cloth,” Parse Journal 11 (Summer 2020): http://parsejournal.com/article/thats-not-your-story-faith-ringgold-publishing-on-cloth/.

6

Latimer, “‘We Can Make It Come True’: Faith Ringgold’s Dinner At Gertrude Stein’s,” 133.

7

Roth, “Of Cotton and Sunflower Fields: The Makings of The French and The American Collection,” 50.

8

Wallace, “The French Collection: Momma Jones, Mommy Fay, and Me,” 16-17.

9

“Zora is being and making a classic of the black folk culture and language we are always being so ashamed of.” Ringgold, Dinner at Gertrude Stein’s, transcription of quilt story appears in Dancing at the Louvre: Faith Ringgold's French Collection and Other Story Quilts, 140.

10

Faith Ringgold, interview in “THREADS Episode,” Craft in America, PBS, May 11, 2012. https://www.pbs.org/video/craft-in-america-episode-viii-threads/

11

Ibid.

12

Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art + Textile Politics, (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2017), 216.

13

With the exception of Echoes of Harlem, 1980, and perhaps a few of her other quilts early on in her career, Ringgold relies on assistants to stitch her quilts. Roth, “Of Cotton and Sunflower Fields: The Makings of The French and The American Collection,” 56. Ringgold, interview in “THREADS Episode.”

Image Bibliography

Cameron, Dan, Richard J. Powell, Michele Wallace, Patrick Hill, Thalia Gouma-Peterson, Moira

Roth, and Ann Gibson, Dancing at the Louvre: Faith Ringgold's French Collection and Other Story Quilts. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1998.

Craft in America. “THREADS Episode.” PBS, May 11, 2012. Video, 53:25. Accessed

November 22, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/video/craft-in-america-episode-viii-threads/

Newark Museum, http://gallery.newarkmuseum.org/view/objects/asitem/items$0040:2962116

Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, https://www.houldsworth.co.uk/artists/73-faith-ringgold/works/

9678-faith-ringgold-the-flag-is-bleeding-2-american-collection-6/

Bibliography

Auther, Elissa. String, Felt, Thread: The Hierarchy of Art and Craft in American Art.

Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. 2010.

Bryan-Wilson, Julia. Fray: Art + Textile Politics. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

2017.

Cameron, Dan, Richard J. Powell, Michele Wallace, Patrick Hill, Thalia Gouma-Peterson, Moira

Roth, and Ann Gibson, Dancing at the Louvre: Faith Ringgold's French Collection and Other Story Quilts. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1998.

Craft in America. “THREADS Episode.” PBS, May 11, 2012. Video, 53:25. Accessed

November 22, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/video/craft-in-america-episode-viii-threads/

Hemmings, Jessica. “That’s Not Your Story: Faith Ringgold Publishing on Cloth,” Parse

Journal 11 (Summer 2020). Accessed November 22, 2020.

http://parsejournal.com/article/thats-not-your-story-faith-ringgold-publishing-on-cloth/.

hooks, bell. “An Aesthetic of Blackness: strange and oppositional”. In The Object of Labor: Art,

Cloth, and Cultural Production, edited by Joan Livingstone and John Ploof, 315-332. Cambridge, MA and London: School of the Art Institute of Chicago and The MIT Press, 2007.

Hurston, Zora Neale. Their Eyes Were Watching God. New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

1937, 1990.

King, Richard H. Race, Culture, and the Intellectuals, 1940–1970. Baltimore, MD: Johns

Hopkins University Press. 2004

Latimer, Tirza True. “‘We Can Make It Come True’: Faith Ringgold’s Dinner At Gertrude

Stein’s.” English Language Notes 51.1 (Spring/Summer 2013), 129-135.

Mahdawi, Arwa. “The quilts that made America quake: how Faith Ringgold fought the power

with fabric,” The Guardian. June 4, 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jun/04/faith-ringgold-new-york-artist-

serpentine-gallery-london