Museums are sterile environments built for able-bodies, built to regulate bodies, or perhaps, not built for bodies at all.

Visitors are expected to respect the controlled sensorial environment in a museum. It is a regulated space, with social rules of conduct that require the body to adhere to ‘strict bodily discipline’ and order. These sites of surveillance demand no touching, no eating, no drinking, no talking or walking loudly. A place to display and flaunt the wealth of capitalist nations.16

![]()

![]() Shannon Finnegan, Do You Want Us Here or Not, 2018. MDO, paint, 72" x 26" x 36"

Shannon Finnegan, Do You Want Us Here or Not, 2018. MDO, paint, 72" x 26" x 36"

[TOP: A blue bench sits against a white wall, on the back of the bench in white text it reads: I’d rather be sitting. On the seat of the bench it reads: Sit here if you agree.

BOTTOM: A blue bench sits against a white wall, on the back of the bench in white text it reads:This exhibition has asked me to stand for too long. On the seat of the bench it reads: Sit here if you agree.]

Shannon Finnegan, Do You Want Us Here or Not, 2018. MDO, paint, 72" x 26" x 36"

Shannon Finnegan, Do You Want Us Here or Not, 2018. MDO, paint, 72" x 26" x 36"[TOP: A blue bench sits against a white wall, on the back of the bench in white text it reads: I’d rather be sitting. On the seat of the bench it reads: Sit here if you agree.

BOTTOM: A blue bench sits against a white wall, on the back of the bench in white text it reads:This exhibition has asked me to stand for too long. On the seat of the bench it reads: Sit here if you agree.]

16. Constance Classen and David Howes, “The Museum as Sensescape: Western Sensibilities and Indigenous Artifacts,” in Sensible objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture. edited by Elizabeth Edwards, Edith Anderson Feisner, and Ruth Phillips (New York: Berg, 2006).

The artist Shannon Finnegan simultaneously calls attention to the structure of the museum that excludes disabled bodies while offering solutions in the form of actual places for rest as benches and seating. The artwork functions as an intervention in spaces made for able bodies.17 Their series, Do you want us here or not,18 consists of blue wooden seating with phrases such as: "This museum has asked me to stand too long, sit here if you agree." and “It was hard to get here, rest if you agree.” These places to pause act as a subtle form of protest or refusal. Rest-refusal. When sitting upon their benches, the body is resting in solidarity.

17. Well, actually, all bodies require rest, more rest than the demands of capitalism allow.

18. Which is a great title, by the way.

18. Which is a great title, by the way.

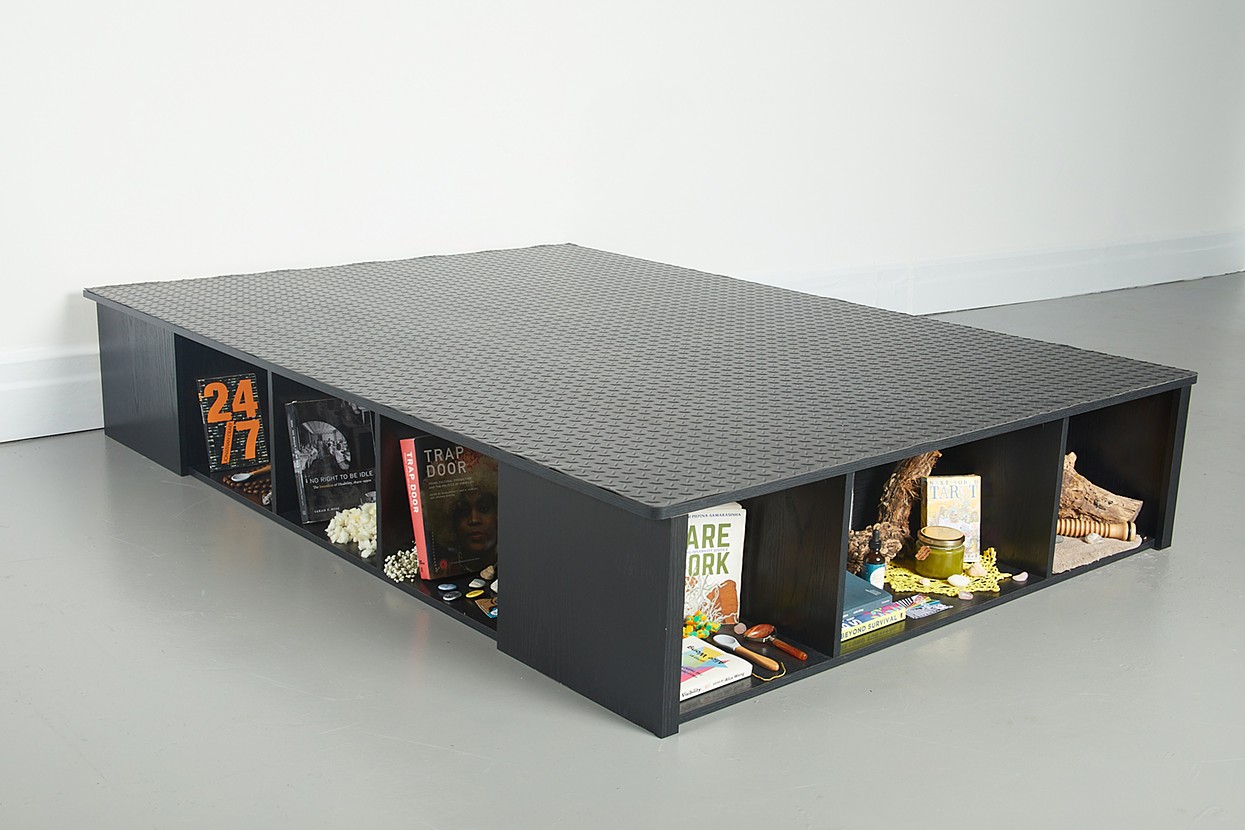

Alex Dolores Salerno, At Work (Grounding Tactics), 2020. Diamond Plate Rubber Flooring, Bedframe, Books, Stim Toys, Rocks, Wood, Candle, Hourglass, Tarot Cards, Heating Pad, Memory Foam, and Various Objects, 77" x 56" x 14". Image by Mike DiFeo

Alex Dolores Salerno, At Work (Grounding Tactics), 2020. Diamond Plate Rubber Flooring, Bedframe, Books, Stim Toys, Rocks, Wood, Candle, Hourglass, Tarot Cards, Heating Pad, Memory Foam, and Various Objects, 77" x 56" x 14". Image by Mike DiFeo[On a grey floor, against a white wall is a black bed frame shot at a 3/4th angle. The bed frame has built-in storage cubbies, 6 are visible. Inside of each cubby are various objects and ephemera, all intentionally placed, sculptures within the sculpture. Some of the objects that are visible include books (such as Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha and 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep by Jonathan Crary), rocks, a jar of salve, and the fuzzy surface of a heating pad. In the place of a bed is industrial black diamond plate rubber flooring cut precisely to the dimensions of the bed frame and laid flat across the surface. The diamond plate creates a textured patterned surface.] AltText courtesy of the artist's website.

Alex Dolores Salerno, At Work (Grounding Tactics), detail. Image by Mike DiFeo

Alex Dolores Salerno, At Work (Grounding Tactics), detail. Image by Mike DiFeo[TOP: This is a detail shot of At Work (Grounding Tactics) of the middle cubby on the side of the bed frame. Two books are propped up in a pile of shredded memory foam, Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure by Eli Clare and No Right to Be Idle: The Invention of Disability, 1840s–1930s by Sarah F. Rose. In the middle of the books is a small zine opened to a page that depicts exit signs and the word “laboratory”. In the front right are 2 stim toys, a black tangled interlocked toy and a red plastic mesh finger trap with an enclosed marble. Behind are two antique glass jars, one contains used bandaids and the other contains a prescription paper, a handwritten note with the word “Antioxidants” visible, and a sprig of a purple amaranth plant.] AltText courtesy of the artist's website.

BOTTOM: This is a detail shot of At Work (Grounding Tactics) of the middle cubby on the end of the bed frame. On the right side Next World Tarot by Cristy Road and a jar of green salve sit on a yellow fabric doily. Scattered in front are some small rocks and rose quartz. Next to them is an embroidered patch that depicts a rainbow emerging from black and white lines and reads “It’s time to dream think see act beyond prisons”, and tincture bottle that reads “ Love in times of crisis” On the right is the book Carceral Capitalism by Jackie Wang lying on top of Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement edited by Ejeris Dixon and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, and propped up behind them is Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds by Adrienne Maree Brown. In the back center is a long curvy piece of textured wood and a tall white candle.] AltText courtesy of the artist's website.

The artist Alex Dolores Salerno also creates sites of rest that refuse the regulation of bodies in public spaces and elevates rest’s importance. Their interactive sculpture, At Work (Grounding Tactics), is a bed as an art object. The bed offers the viewer a place to rest. When interacted with, the sculpture becomes an altar for the body and an altar for rest. There are cubbies around the bed filled with disability related objects and ephemera, such as books about rest and care, stim toys, and a heating pad. Each cubby is its own small altar to the crip body. The top of the bed is covered in a diamond plate rubber mat. The kind of industrial rubber mat used for non-slip surfaces, an essential implement for disability.

There is a long-standing historical precedent of excluding the disabled body from the protection of the many. Capitalism has trained society to fear the other, the poor, the disabled. The Ugly Laws were passed throughout the United States in the late nineteenth century marginalizing people with disabilities for fear that their difference- anything challenging the status quo - might be contagious and was dangerous to the state.

“In 1907, Alabama, for instance, passed laws prohibiting entrance into the state ‘of persons of an anarchistic tendency, of paupers, of persons suffering from contagious or communicative diseases, of cripples without means and unable to perform mental or physical service, of idiots, lunatics, persons of bad character, or of any persons who are likely to become a charge upon the charity of the State, and all such as will not make good and law-abiding citizens.’19

Marginalization is a historical norm. 20 But these beliefs didn’t grow out of Alabama; similar laws were established as early as 1867 (two years after the end of the Civil War) in San Francisco.21 These laws spread across the country, similar to how a disease might spread. Fear of disease spread, the disease of the contaminated other, which was believed to be caused by the immigrant, the poor, the mutilated, the maimed, and the disabled. Often based on aesthetic opinion that the disabled or “other” body was dirty, unclean, undesirable - abject.

[A group of pillowcases huddle together in a corner. They are stained from use and filled with medical ephemera from the artist and their friends, family and community. While removed from the bed, their form calls to mind the labor of rest and the collectivity of care. The obscured contents of the pillowcases negate the demand placed on pathologized subjects for a reveal, explanation or diagnosis. This opacity redirects us to view the forms as entities joined together in conversation and as a network of support. As a forever ongoing and growing work, the composition and number of pillowcases changes responding to the passage of time and installation site.] Alt-text courtesy of the artist.

Salerno’s work, Pillow Fight, consists of pillow cases that contain medical ephemera, forcing us to confront the abject body in the sterile space of the gallery. They are stained yellow from use, and are bulging at the bottoms, similar to the bulge of belly fat. Although the pillows invite one for rest, their filling suggests sharp edges that might cause pain if one rested on them. The stains also call to mind an intimacy and privacy of the bed and undergarments. The stains suggest the abject and ugly body, similar to the abject stigma of the visibly disabled body.

19. Susan Schweik, The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 168.

20. This thinking is still deeply ingrained in society, even now, as everyone jumps right “back to normal,” I am afraid and skeptical (as are many disabled people) of the CDC’s “Great Un-Masking” which feels reckless and premature. (We/humans are the test subjects.) There are still so many people who are vulnerable, even post-vaccine. The blatant eugenics tactics (sacrifice the weak, to save the economy) over the past 15 months for the comfort (unmasking) of the “healthy” (privileged, able-bodied) and capitalism (the economy) continues to further marginalize the disabled, leaving them behind and stuck at home, or dead. A study published in the UK revealed that 22,500 disabled people died due to COVID-19 between March and May 2020, compared with about 15,500 non-disabled people. https://www.disabilitynewsservice.com/coronavirus-call-for-inquiry-and-urgent-action-after-shocking-disability-death-stats/ Our society values the most fit, “healthy” individuals: the most productive. This valuing system deems disabled lives as unworthy. Eugenics, popularized in the late nineteenth century in the US and UK, (and later in Nazi Germany) is the eradication of “undesireables” through the forced sterilization and murder of mentally and physically disabled people (among other populations deemed ‘unfit’) who are believed to be a “burden on society”, and is still practiced today.

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/column-the-false-racist-theory-of-eugenics-once-ruled-science-lets-never-let-that-happen-again

https://www.newstatesman.com/society/2010/12/british-eugenics-disabled

21. Susan Schweik, The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 168

Capitalism says that disabled, tired bodies that spend too much time in bed are useless.

The disabled body subverts expectations about how a body should look, perform, and produce. The unstructured and horizontal resist the demands of neo-capitalism on the body. Pipzna-Samarasinha recognizes that “Capitalism says that disabled, tired bodies that spend too much time in bed are useless. Anyone who cannot labor to create wealth for owners is useless. People are valued only for the wealth they labor to build for capitalism; crips are useless to capitalism.” But she argues that liberation, organizing, and creating can happen in bed when one has the space and time to dream. Allowing our disabled bodies to reclaim time – to rest – provides alternate possibilities for survival.

Jillian Crochet is an interdisciplinary artist based in the Bay Area, working in sculpture, video, and performance, to confront grief and disability. Her practice seeks to liberate the disabled body from normalized marginalization and oppression. She is a current Graduate Fellow at Headlands Center for the Arts and a 2020 Artist in Residence at Art Beyond Sight’s Art & Disability program. She earned her BFA from the University of Alabama in 2007 and a MFA in Fine Arts from California College of the Arts in 2020.