Instagram influencer @kinderwh0re.clown demonstrating a contemporary clowncore outfit + makeup look. Pinterest

Maximalism, Camp, Queer Clown Core,

& The New Gilded Baroque

By Jackie Andrews

Guest Editor Sienna Freeman

While period dramas like Netflix’s Bridgerton and HBO’s The Gilded Age have become perennial pop culture references, the aesthetics of the Regency era (in which Bridgerton is set) and The Gilded Age (named, of course, for its respective period) have resurfaced in American fashion, along with a variety of looser interpretations and references of the surrounding time periods including Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassicism, and Victorian. Both in tandem and in counterpoint, 1980s and Y2K revival, the sunny psychedelics of the ‘60s and ‘70s, and ever-changing, ever-glitchy Futurism have flourished. Spilling over from the depths of social media and the fashion runways, into street style, and even your local Suburban mall or high school parking lot, a variety of these aesthetic influences and references have been dubbed _______–core.

1. Some of Netflix’s Bridgerton cast in costume; 2. Some of the Bridgerton cast in Regency-inspired contemporary fashion in British Vogue.

Fashion and lifestyle trends aside, it’s become a linguistic one of sorts: the mysterious desire to add “–core” to the end of basically any word, and BOOM! Suddenly, you have an ~aesthetic~. Examples include: cottagecore (also known as cabincore, among others), craftcore, Barbiecore (bound for runway takeovers, I’m certain, immediately following July 2023’s highly anticipated release of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie), royalcore or, unambiguously, Bridgertoncore, normcore, millennialcore, clowncore, kidcore, gothcore… the list goes on. 1

An assortment of –core aesthetic examples, including (clockwise from top left): “Barbiecore”, demonstrated by Margot Robbie as Barbie in Greta Gerwig’s forthcoming film; the cast of Seinfeld, as prime examples of “Normcore”; Bella Hadid clad in “Kidcore” accessories; and Florence Pugh as Amy March, another example of Regency-meets-cottagcore, in Greta Gerwig’s 2019 adaptation of Little Women.

If I attempted to describe the wide-ranging aesthetics of the past several years (think 2020 onwards), it would be, in a word: “–core” (if that can even be counted as a word, as it’s more of a suffix in this case). The term has quickly become entrenched in our vernacular, at times seemingly devoid of meaning –or at least, nebulous; so much so that there are glossaries of –core terms, and even satirical –core name generators (an excellent way to waste 25 minutes, highly recommend). 2

![]()

If I attempted to describe the wide-ranging aesthetics of the past several years (think 2020 onwards), it would be, in a word: “–core” (if that can even be counted as a word, as it’s more of a suffix in this case). The term has quickly become entrenched in our vernacular, at times seemingly devoid of meaning –or at least, nebulous; so much so that there are glossaries of –core terms, and even satirical –core name generators (an excellent way to waste 25 minutes, highly recommend). 2

More to the point: what do you get when you mix all of these things? I’ll posit Chaos–core, if you’ll allow it (alternatively: a mess, depending on who you ask). More importantly, what does this maximalist approach say about our society? That’s where it gets interesting. It’s no secret that in many ways, our current reality often feels pretty bleak. As our nation’s (and our world’s) young people grapple with the emotional, mental, and physical tolls ofthe intersecting crises unfolding in American culture (i.e. the ongoing pandemic, rapidly widening wealth disparities, systemic racism and the rise of white supremacy, erosion of civil rights for BIPOC, LGBTQ+, and reproductive health, and the climate crisis, just to name a fewpressing concerns), zany forms of creative expression seen in social media, fashion, and even contemporary art trends seem to parallel the excessive maximalism of the Baroque and Rococo periods – visually, of course, but also socio-politically and economically.

Let’s talk economics for a moment – there are a wealth of supporting statistics to choose from (and yes, pun very much intended, I am not sorry). In a July 2022 oped from The Hill, contributor Harlan Ullman cited a report by Capital & Main: “Consider the report: ‘The top 0.1 percent and the bottom 90 percent of American households hold close to the same amount of wealth. …It’s one of the statistics most frequently cited to describe the problem of economic inequality in the United States today. Here are some others: Nearly two-thirds of Americans are now living paycheck to paycheck. An estimated 41 percent—135 million people—are considered either poor or low-income. Eighteen percent of households earn less than $25,000 a year. Even before the pandemic hit, one in four Black families had a net worth of zero’.” 3

While these statistics are nothing short of stunning, the piece’s closing line is, perhaps, equally telling:

“Many will dismiss these warnings, as did Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. But make no mistake: America’s wealth inequality is an IED that’s ready to detonate.” 4

Unfortunately, America’s ‘ruling class’ seems just as out of touch as the infamous Marie Antionette (fittingly nicknamed Madame Deficit during the French Revolution). While the wealth gap has widened significantly in recent years (most especially over the course of the pandemic – but more on that later), the parallels between America’s socioeconomic conditions and those of pre-Revolutionary France are nothing new. In 2019, Teen Vogue published an oped by writer and organizer Kim Kelly titled “How the French Revolution Is Inspiring Today’s Online Anti-capitalists” that manages to serve up both wit and levity alongside plenty of historical accuracy and political insight on the American Labor Movement, with a lens trained specifically on media influences including music and YouTube stars. As for parallels, Kelly’s opening paragraph is scathing:

Let’s talk economics for a moment – there are a wealth of supporting statistics to choose from (and yes, pun very much intended, I am not sorry). In a July 2022 oped from The Hill, contributor Harlan Ullman cited a report by Capital & Main: “Consider the report: ‘The top 0.1 percent and the bottom 90 percent of American households hold close to the same amount of wealth. …It’s one of the statistics most frequently cited to describe the problem of economic inequality in the United States today. Here are some others: Nearly two-thirds of Americans are now living paycheck to paycheck. An estimated 41 percent—135 million people—are considered either poor or low-income. Eighteen percent of households earn less than $25,000 a year. Even before the pandemic hit, one in four Black families had a net worth of zero’.” 3

While these statistics are nothing short of stunning, the piece’s closing line is, perhaps, equally telling:

“Many will dismiss these warnings, as did Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. But make no mistake: America’s wealth inequality is an IED that’s ready to detonate.” 4

Unfortunately, America’s ‘ruling class’ seems just as out of touch as the infamous Marie Antionette (fittingly nicknamed Madame Deficit during the French Revolution). While the wealth gap has widened significantly in recent years (most especially over the course of the pandemic – but more on that later), the parallels between America’s socioeconomic conditions and those of pre-Revolutionary France are nothing new. In 2019, Teen Vogue published an oped by writer and organizer Kim Kelly titled “How the French Revolution Is Inspiring Today’s Online Anti-capitalists” that manages to serve up both wit and levity alongside plenty of historical accuracy and political insight on the American Labor Movement, with a lens trained specifically on media influences including music and YouTube stars. As for parallels, Kelly’s opening paragraph is scathing:

“Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. It was a time of rampant, crushing inequality; the über-wealthy upper class of a powerful nation-state sat upon gilded thrones, while the lower classes scraped out a miserable existence. Aristocrats depleted the nation’s treasury in pursuit of pleasure while the serrated class divides between the haves and have-nots grew sharper, and eventually fanned the flames of a full-scale rebellion. In 2019, this state of affairs sounds familiar — but this was 18th-century France, not the modern-day U.S.” 5

If this is Kelly’s piece in 2019, I certainly want to hear what she has to say on the topic today; but, more to my point, the profusion of articles, think pieces, and even lighter, listicle-esque fare addressing historical precedent of wealth disparities, anticapitalism movements, and working class uprising from unlikely sources such as Teen Vogue is particularly interesting. It speaks to the increasingly politically motivated, activist–minded readership of Gen Z and Millennials who want their fashion sense and trend reports to reflect both pop-cultural hipness and a sense of political shorthand (because we contain multitudes). As for food insecurity in the young working class (among many others), I guess we could always eat cake, as goes Marie Antoinette’s famously rumored line (as it turns out, it’s likely nothing more than an urban legend of her time). 6

Maybe you’re not sold on the comparison to Revolutionary-era France; what about the Gilded Age? Let’s shift the timeline and look at a few other statistics, shall we? In December 2021, CBS News reported:

Of course, these numbers are slightly outdated in 2023, but even without exact statistics, I’d posit that it’s a very safe assumption that the disparity has worsened dramatically, especially given the well-documented exorbitant wealth accumulation due to corporate profits over the course of the pandemic. The report addresses that as well:

Maybe you’re not sold on the comparison to Revolutionary-era France; what about the Gilded Age? Let’s shift the timeline and look at a few other statistics, shall we? In December 2021, CBS News reported:

“The globe’s 2,750 billionaires now control 3% of all wealth, up from 1% in 1995 — that makes them wealthier than half the planet… in the U.S., the return of top wealth inequality has been particularly dramatic, with the top 1% share nearing 35% in 2020, approaching its Gilded Age level, compared with less than 25% in 1970, the report noted.” 7

Of course, these numbers are slightly outdated in 2023, but even without exact statistics, I’d posit that it’s a very safe assumption that the disparity has worsened dramatically, especially given the well-documented exorbitant wealth accumulation due to corporate profits over the course of the pandemic. The report addresses that as well:

“The COVID-19 pandemic has only accelerated wealth accumulation by the ultra-rich, with the report noting that 2020 marked the biggest increase in the share of global billionaire wealth ever recorded. America’s billionaires have seen their total wealth jump by 70% — the equivalent of more than $2 trillion — since the start of the pandemic.” 8

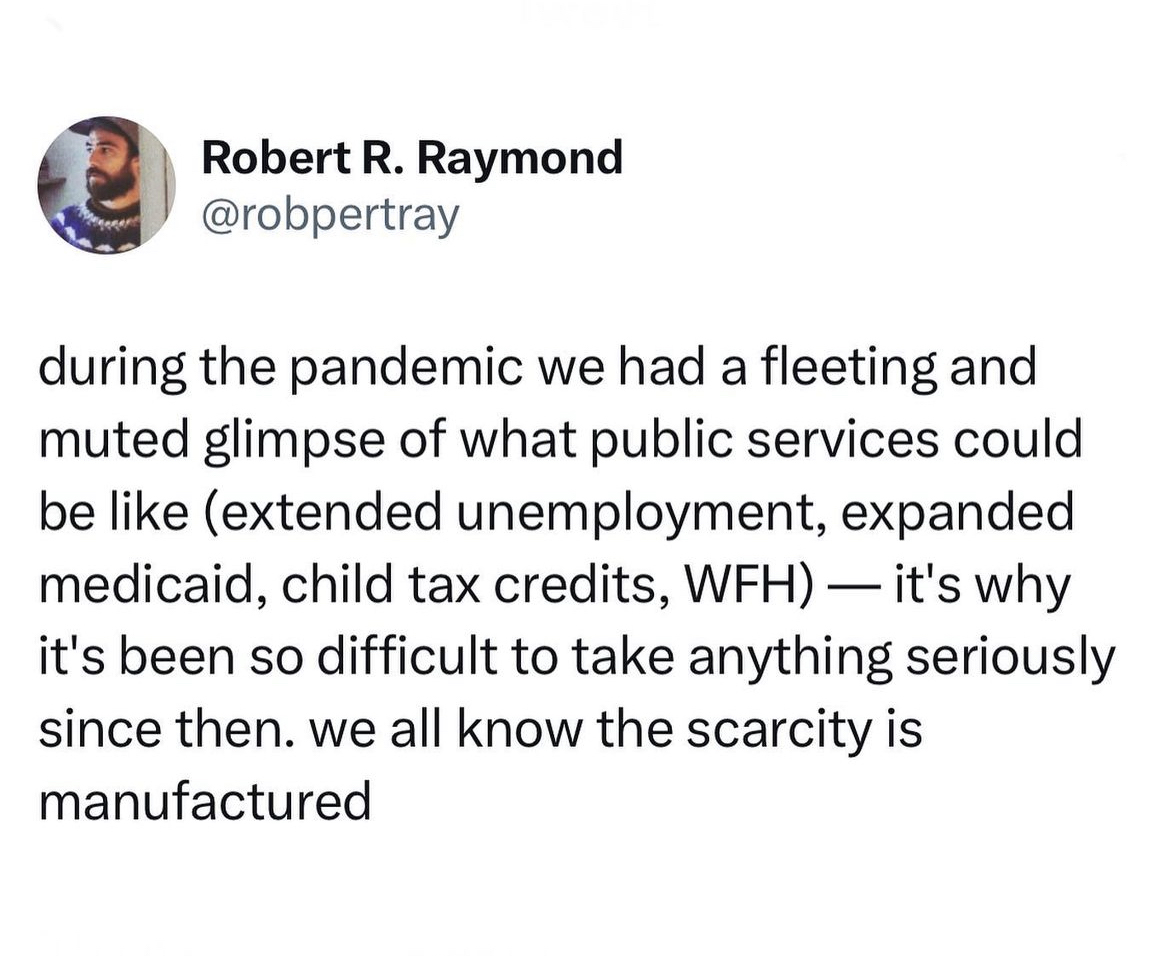

In the wake of early-pandemic-era financial and public health support infrastructure, and with these statistics in mind, combined with the tidal waves of unionization, strikes, and workers’ rights campaigns in the U.S., economic desperation and urgency has bred momentum for much of the working and middle class. A viral tweet circulating in April 2023 attributed to Robert R. Raymond addressed the mirage we’re witnessing so concisely:

(Maybe we’re born with it, maybe it’s unfettered capitalism!)

Now that the economic backdrop is set, and we’ve begun to consider how the socio-political leanings of the Gen Z and Millennial generations influence pop cultural trends, let’s return to this issue of fashion—how does all this possibly relate to clowncore, cottagecore, and the like?

Simply put, it’s camp at its finest.

Coinciding with the 2019 Met Gala theme, explanations of camp appeared across a range of publications; a personal favorite article on the topic is from the New York Times, featuring a smattering of hilariously accurate camp examples—from dog shows to Cher, Versace to Supreme, professional wrestling to the 1985 Clue movie—along with Susan Sontag’s famous descriptions as an opener:

“During the pandemic we had a fleeting and muted glimpse of what public services could be like (extended unemployment, expanded Medicaid, child tax credits, WFH) — it’s why it’s been so difficult to take anything seriously since then. We all know the scarcity is manufactured.” 9

(Maybe we’re born with it, maybe it’s unfettered capitalism!)

Now that the economic backdrop is set, and we’ve begun to consider how the socio-political leanings of the Gen Z and Millennial generations influence pop cultural trends, let’s return to this issue of fashion—how does all this possibly relate to clowncore, cottagecore, and the like?

Simply put, it’s camp at its finest.

Coinciding with the 2019 Met Gala theme, explanations of camp appeared across a range of publications; a personal favorite article on the topic is from the New York Times, featuring a smattering of hilariously accurate camp examples—from dog shows to Cher, Versace to Supreme, professional wrestling to the 1985 Clue movie—along with Susan Sontag’s famous descriptions as an opener:

9 Twitter

“In 1964, [Sontag] defined camp as an aesthetic ‘sensibility’ that is plain to see but hard for most of us to explain: an intentional over-the-top-ness, a slightly (or extremely) ‘off’ quality, bad taste as a vehicle for good art. Camp is artificial, passionate, serious, Sontag writes. Camp is Art Nouveau objects, Greta Garbo, Warner Brothers musicals and Mae West. It is not premeditated — except when it is extremely premeditated….Still, Sontag’s treatise remains the top-cited attempt to define a slippery concept.” 10

As a lover of all things kitsch, camp, and glittery flamboyance, it sparks joy for me to emphasize that camp is thoroughly queer—a notion that is notoriously largely ignored by Sontag. A Refinery29 article cites the earliest usage of the term in 1909, in “homosexual slang,” according to Merriam-Webster. 11

The article also includes renowned writer and critic Moe Meyer’s assertion of camp as the “strategies and tactics of queer parody,” with the addition that camp likely originates from Black culture, as noted former Essence editor-in-chief Constance White. 12

Left: Sam Smith, an ongoing example of queer camp: left, in ‘The Biggest Dress’ by Tomo Koizumi; right, in a custom inflatable suit by HARRI, worn at the BRIT Awards 2023.

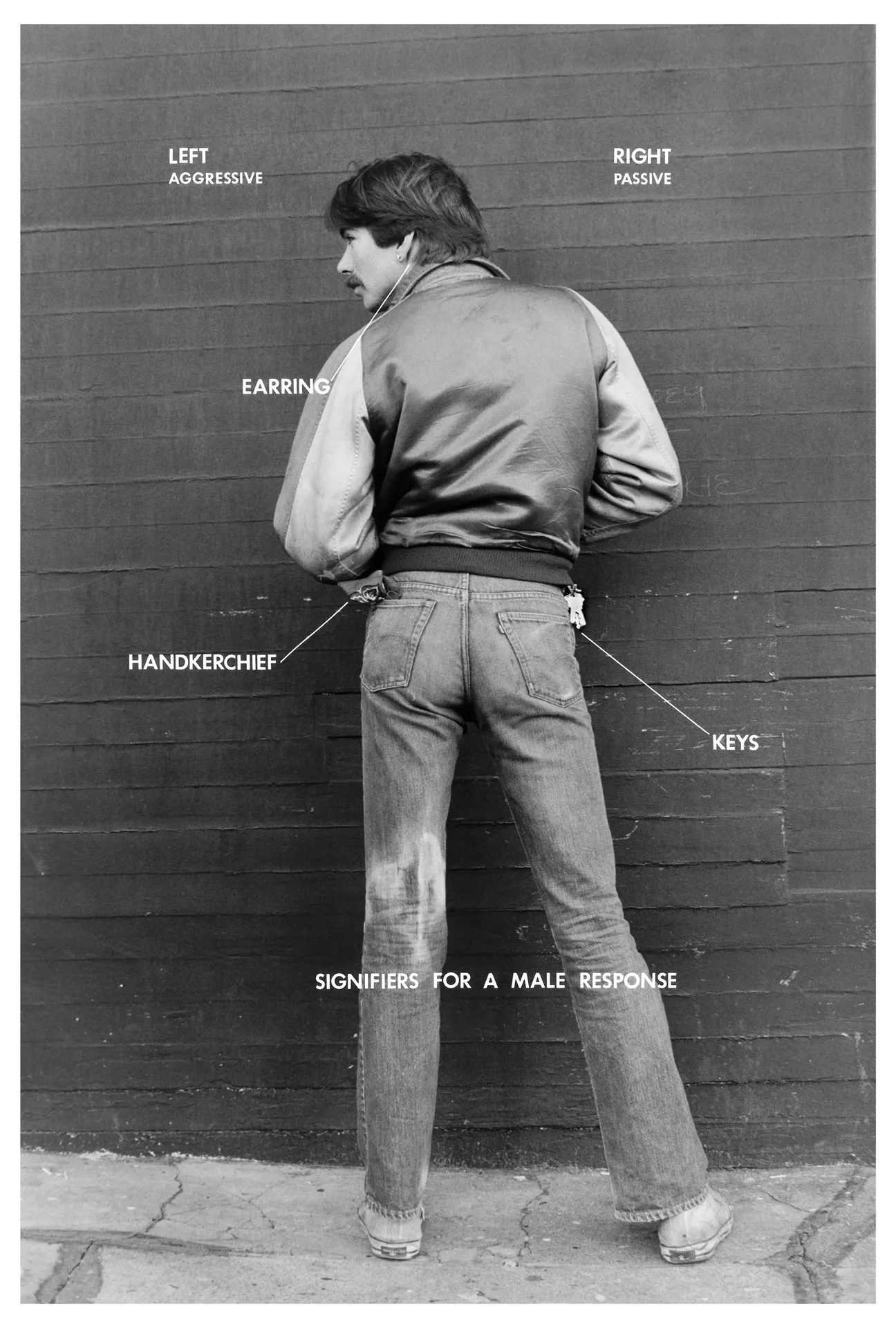

While camp returned with a vengeance within mainstream fashion and discourse in 2019 (in accordance with the Met Gala), queer coding and camp has been setting the trend for much longer (hanky code and drag spring to mind); clowncore, cottagecore, whatevercore is just an expansion (and mainstream-ification) of it.

Signifiers for a Male Response, from the series Gay Semiotics, 1977. © Hal Fischer. This artwork is a representation of hanky code; it’s worth noting that hanky code is relevant to all genders and is a queer signifier across a range of LGBTQIA+ identities.

The campiness of our love of all things “–core” offers us an opportunity to play dress-up in our daily lives; for a generation that ostensibly worships at the altars of both therapy and TikTok (again—multitudes), we’re all thoroughly devoted to the collective reclamation of the inner childand playing dress-up seems like an excellent outlet.

Acting as a balm and a coping mechanism of sorts, flamboyant and exuberant fashion and art trends—characterized by vibrant, clashing patterns, flashy makeup, excessive glitter and embellishments, to name a few—speak to a complicated mixture of defiantly joyful self-expression tinged with a sense of nihilism precipitated by the world seemingly ablaze around us. Beyond the innocent fun of dress-up, I’d posit our “–core” obsessions serve even greater metaphorical purposes: they allow us to embody values and lifestyles that we may not currently have the agency or means to fabricate in our current lives. Instead, we daydream and manifest through self-expression to the extreme. If that’s true, consider the possible cues that the many give us: perhaps clowncore and kidcore are the celebratory exaltations of the queer inner child, while cottagecore might suggest a yearning for simplicity and solitude of rural life (either contemporarily, or of a bygone era). Gothcore might hint at a resurgent teen angst, while Barbiecore could represent a particularly glossy set of rose-colored glasses (or, perhaps a sugar-coated form of stealth feminism—we’re speculating, here). One thing’s for sure: they all offer a decidedly sweet, slightly silly escape hatch from the myriad horrors of our current reality—and one could argue, an increasingly necessary form of self-care.

https://www.them.us/story/what-is-the-hanky-code-gay-flagging

Three examples of clowncore Left to right: Bella Hadid walking the MOSCHINO runway in 2020; an Instagram influencer @kinderwh0re.clown demonstrating a contemporary clowncore outfit + makeup look; Harry Styles in a (slightly) more minimal approach to clowncore, clad in Swarovski overalls for the 2023 Grammys.

In this way, the function of the “–cores” transcends the technical definition and intention of the term aesthetic, which—in its simplest form—is the philosophical study of beauty and taste. 13

It seems an understatement to note that the philosophical writings of Immanuel Kant and Georg Hegel (among others) are a far cry from the uber–niche “aesthetics” mined from the depths of TikTok. (Not to mention, the density of Kant and Hegel’s texts are simply incompatible with the increasingly narrow, 140-character, “hot-take”-riddled content market that dominate today’s media landscape.) Regardless: the “–cores”; are not only highly individualistic aesthetic codes, but polysemic in nature—they serve increasingly unique functions as signifiers of identity and lifestyle.

In the more extreme examples, they’re almost serving as real-life avatars (for a generation raised in the internet age, this “leak” from the digital realm seems plausible and unsurprising). In smaller forms, the “–cores” are like accessories, ready to be swapped and layered depending on the day.

In small but mighty ways, they are mood boosters and “jollifiers”, but that by no means makes them frivolous: because even in the smallest instances, they allow us to embody (both literally and figuratively) a personhood that fulfills our personal visions for our lives; they’re physical manifestations of the multitudes we contain.

Perhaps most intriguingly, albeit most importantly: it’s a tool of empowerment—suggesting we might collectively build the world around us to reflect our joy-filled, exuberant visions. After all: you can’t be in the good fight if you’re burnt out on reality, and if playing dress-up gets you through the day, I’m all in. Our contemporary American experience of maximalism in a phrase: the world might be ending, so you might as well wear everything you love at once.

See Jackie’s work online.

@jackiegemcreative

It seems an understatement to note that the philosophical writings of Immanuel Kant and Georg Hegel (among others) are a far cry from the uber–niche “aesthetics” mined from the depths of TikTok. (Not to mention, the density of Kant and Hegel’s texts are simply incompatible with the increasingly narrow, 140-character, “hot-take”-riddled content market that dominate today’s media landscape.) Regardless: the “–cores”; are not only highly individualistic aesthetic codes, but polysemic in nature—they serve increasingly unique functions as signifiers of identity and lifestyle.

In the more extreme examples, they’re almost serving as real-life avatars (for a generation raised in the internet age, this “leak” from the digital realm seems plausible and unsurprising). In smaller forms, the “–cores” are like accessories, ready to be swapped and layered depending on the day.

In small but mighty ways, they are mood boosters and “jollifiers”, but that by no means makes them frivolous: because even in the smallest instances, they allow us to embody (both literally and figuratively) a personhood that fulfills our personal visions for our lives; they’re physical manifestations of the multitudes we contain.

Cultural affinity for the “–cores” can be interpreted as a quiet defiance, with a wink; a proud expression of self, and a love letter to the type of world we’d like to live in.

Perhaps most intriguingly, albeit most importantly: it’s a tool of empowerment—suggesting we might collectively build the world around us to reflect our joy-filled, exuberant visions. After all: you can’t be in the good fight if you’re burnt out on reality, and if playing dress-up gets you through the day, I’m all in. Our contemporary American experience of maximalism in a phrase: the world might be ending, so you might as well wear everything you love at once.

See Jackie’s work online.

@jackiegemcreative