The everyday objects that surround us are a remix of times, colors, patterns, textures, origins, and sources. Everything comes from somewhere, nothing appears from outside a context.

The history of a textile is embedded within its fibers, through its threads, in the core of its weave, present in every stitch, in every layer of printed pattern, and especially present in its name.

Ingrained in my language, my Mexican-Spanish experience of the world, are a series of terms that carry a whole identity with them: “Manila,” associated with folders, mangoes, and mantones. I have always bought Manila folders, those yellowish objects made of Manila paper. When in season, of all the varieties available, I would always buy Manila mangoes. In my manufactured idea of Spain, I would always picture a woman covering her shoulders with a beautiful embroidered silk shawl commonly worn by flamenco dancers, a Mantón de Manila. There is a common element in all of these seemingly disconnected objects of my world: Manila, a name that carries the remains of a long and complex history.

My interest in the use of this word started with a story my grandmother told me. She travelled the world, and I travelled along with her through her stories. When she visited the Philippines she went to a market and grabbed a mango, immediately the store keeper said, “Oh, you want to buy that Mexican mango?” This question perplexed her, she knew she was holding a Manila mango. From this perplexing story a larger concern emerged for me: where are these mangoes really from? Do they come from an in-between location? Are these mangoes grown in the middle of the Pacific ocean?

¿Mango Manila? 2020. Materials: Digital collage

Manila is such a distant place and yet I have coexisted with its legacy in the most essential and quotidian aspects of my life;

Mexico is full of Manila. Its discreet presence through names of things is witness to a historical legacy because my country and the capital of the Philippines were connected for almost three centuries. During colonial times, from 1565 to 1815, there was a commercial trade route in place between Asia and Europe through Mexico: the Manila Galleon. These Spanish trading ships travelled regularly across the Pacific Ocean, back and forth between the ports of Acapulco and Manila, which were both part of New Spain in colonial times. From Manila to Madrid it was commonly stated that “the sun never set in the Spanish empire.”

For a viable trade route to be established there needed to be a way of finding the return trip, a “tornaviaje.” In its very essence, going there depended on the possibility of coming back here. The trade route was inaugurated in 1565 after the Augustinian friar and navigator Andrés de Urdaneta discovered the tornaviaje from the Philippines to Mexico. For over 250 years, the galleon sailed the Pacific Ocean bringing to the Americas cargoes of luxury goods, such as spices and porcelain, in exchange for silver. The route also created a cultural exchange that shaped the identities and culture of the countries involved: Manila as a portal to Asia, Mexico as a transition to Europe. Once they arrived in Acapulco, the shipments would be transported across the Mexican territory to Veracruz, the Western port of Mexico, where ships would sail again towards Spain.

Return. 2020 Materials: Digital collage

.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Mantel de Manila. 2020. Mantel de Manila meets Manila broom

Last February, I had the opportunity to travel to the Philippines to be part of the Third Kamias Triennial. I thought of my own trip as a cultural tornaviaje: a return to a ground zero of linguistic mythology.

As I physically travelled back, I had the feeling of returning to a place I had never been to before. My body felt the weight of the distance. I carried materials to bring back with me, attempting to respond to the centennial trade. Like an embodied galleon, I aimed to establish a dialogue with these histories. But how? The answer was simple: through material.

The project resulted in a series of objects I made in dialogue with material histories. First, I created a series of remixed-Mantones de Manila. In my 2020 version, the mantones were no longer made out of precious silk but of plastic. I used a Mexican flower plastic print tablecloth, for its everyday quality, for its immediacy, and especially for its name, since in Spanish a tablecloth is appropriately called a “mantel”. My mantón was a square mantel, folded in half along the center, transforming in two overlapping triangles. The pattern on the surface was reminiscent of the fruits and flowers that usually adorn an original mantón, but in my version these forms were superimposed using foldable paper decorations made out of “papel de china” made in the Mexican state of Puebla. I selected this material for its name, embedding the Chinese origin of these objects through words. Paper versions of grapes, oranges, pears, and apples were attached to the surface of the mantón adding dimension to the cloth. My mantones also included fringe, which is essential, for it is the fringe that will swirl in the air and complete the movement of the object through the steps of a flamenco dancer. Through its fringe a mantón comes to life, it can dance. This blue mantón melts into neon yellow stripes, glowing.

Left: Manta de Manila. 2020. Cotton fabric made in Mexico, tissue string made in China

Right: Manila sobre Manila. 2020. Materials: Wax crayon drawing on Manila paper

Right: Manila sobre Manila. 2020. Materials: Wax crayon drawing on Manila paper

For my next material investigation I set myself with the challenge of removal, rather than addition. In a sense, this second mantón explored the possibility of a simplification of form. I made a mantón that attempted to break down the form to its essence, I removed the color from the material center, and transferred it to the fringe. I used natural “manta,” plain cloth that is used extensively in Mexico for traditional clothing, and fringe made out of a t-shirt like fabric bought in New York City. And still, it dances. I continued to expand on the possibility of materials and a mythological return through their use delving into the history of Manila paper. This kind of paper was originally made with a fiber called Abacá, Musa textilis, a species of banana native to the Philippines. Before synthetic textiles came into use, this plant was a major source of high quality fiber and was used to make twine and ropes for ships and for fishing—fascinating for me to think about how in its origin these fibers were tied to the possibility of nautical travel. In its pulp form, this resistant fiber is still used today to produce paper for tea bags, folders, and filters.

With the history of this paper in mind, I started exploring the material possibilities that would return the now two dimensional material in the form of paper sheets, to its original volume. I made Manila mangoes out of Manila paper. Torn sheets of Manila paper, the pulp hydrated and mixed, spilling its yellowness out of the blender: a return trip for the material itself. And then, my hands pressing it tight forming a mango shape, the fibrous pulp becoming a fruit again, turning sweet through its new form. The piece was finished when I found a mango basket in a market in Manila to display the returning mangoes.

Left and above

Left and aboveMangos de Manila. 2020. Manila paper pulp made in Mexico, glue, fruit basket made in The Philippines

below

Pabitin (Antipodes piñata) 2020. Pabitin made in The Philippines, yellow plastic string, neon pink string made in China, fresh mangosteen

During my time in Manila I visited endless markets in search of a form, and what I found was a celebration. The pabitin is an object used for a game played at birthday parties, it consists of bamboo sticks wrapped with scrap metallic paper that form a strong reticular structure. This object operates as a surface from which toys are tied, and once suspended, makes children jump to try and reach their prize. The gesture itself is reminiscent of the movement necessary to pick fruits from a tree. And so I encountered this object which carried along a fabulous history. There it was, the pabitin as a historical remix, a kind of flat Mexican piñata from the antipodes. I bought the object and made my own version of the pabitin in which the reticular structure only holds mango steen as an hommage to the most delicious fruit I discovered and ate obsessively in Manila with an overwhelming sense that I might never try its flavor again. My pabitin is an homage to sweetness. The mangosteen’s blackness contrasted with the colorful metallic papers and the neon threads, as moving exclamation points. The pabitin was activated as a stand-in for a tree.

![]()

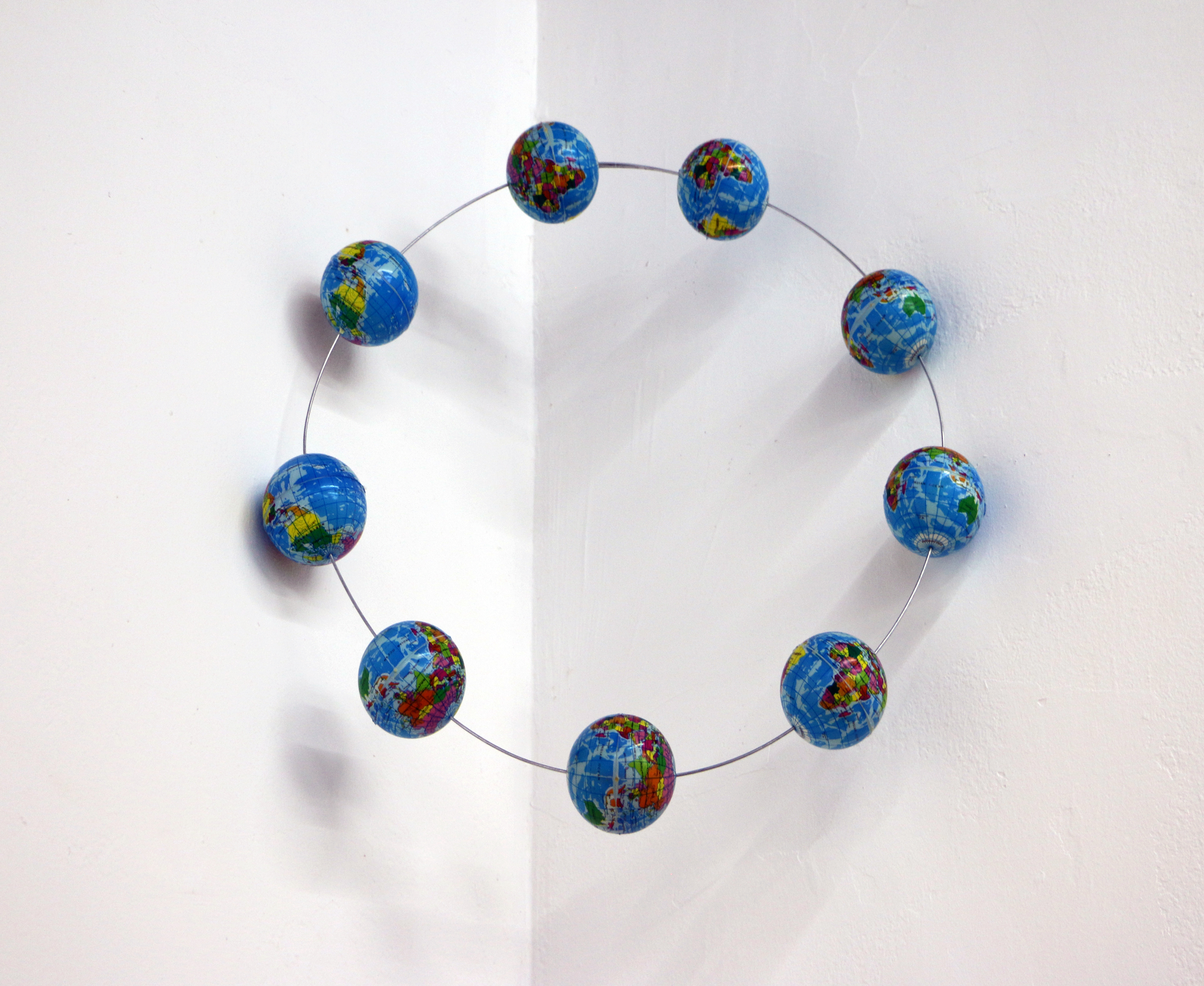

Tornaviaje. 2020 Soft plastic globes made in China, wire

In all, my tornaviaje was a deep textile experience of place, a transformation of space into fibers, and a process of material witnessing of history and myth To look back at the past from the present; to look back at elsewhere from here. And then, to go to that elsewhere, to shorten the distance, and get there again. To arrive, and to be transformed.

Tornaviaje. 2020 Soft plastic globes made in China, wire

In all, my tornaviaje was a deep textile experience of place, a transformation of space into fibers, and a process of material witnessing of history and myth To look back at the past from the present; to look back at elsewhere from here. And then, to go to that elsewhere, to shorten the distance, and get there again. To arrive, and to be transformed.