Against

Seamlessness

by Carolina Magis Weinberg

A handmade textile object is an accumulation of labor: the time that has been invested in its creation resides within it as both presence and absence.

In the moment of production—be it sewing, weaving, embroidering, knitting—every instance of interaction with a textile object implies an amount of labor: hands touching, mending, folding. In parallel, the eventual use of the textile will create the need for additional labor to bring the piece back to its original form: washing, hanging, drying, folding, and ironing. In every case, either resting as a thing in itself, or through the interactions we have with it, textiles are crossed by labor. Textiles are made by hands to be used by hands. In that consideration, even the slightest thought of associating textiles with seamlessness is impossible. If anything, handmade textiles are seamfull.

If there is one tradition of textile-making that could be defined as seamfull, it would be molas, made by the Kuna people in Colombia and Panamá. These pieces are a superposition of textiles where one is cut, thinly folded along a line, and sewn to reveal an underlying color. The seam in this case is essential: without it the other layers would not be revealed. A seamless surface would simply be flat, neutral, unadorned, and boring; whereas, in the process of its making, when the cut and the seam appear, the textile speaks.

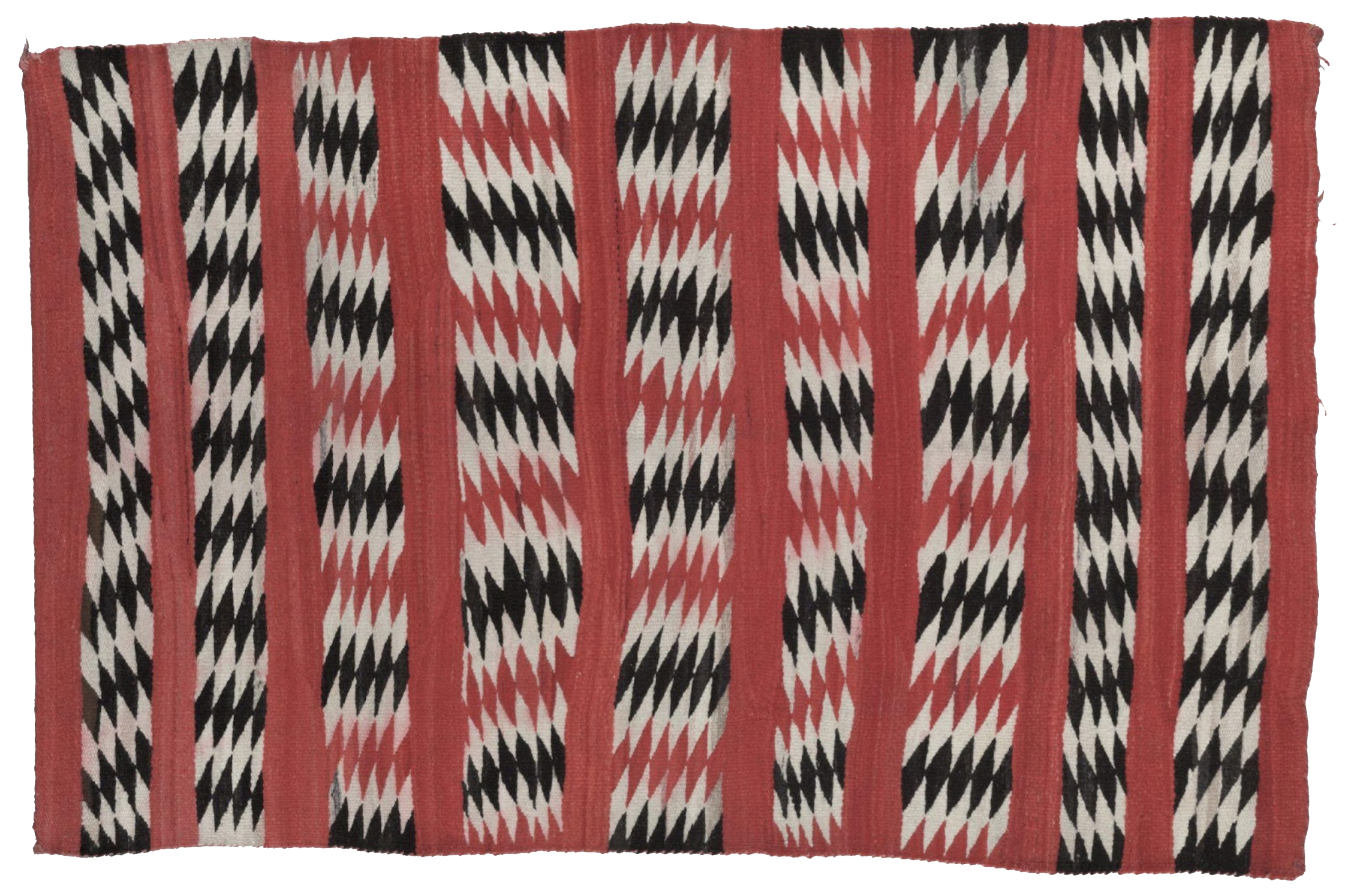

Unknown author, Navajo rug banded with diamond stripes, 1937. Cleveland Museum of Art. Creative Commons

When I travelled to Santa Fe, New Mexico I was researching local textiles and I read a comment on the Native Times website by local weaver Ron Gernanez1, it has stayed with me since, flashing as a guiding light. When they are close to finishing, Navajo weavers will pull out one of the threads in their rugs to avoid perfection. Garnanez explains, “The traditional teaching of the Navajo weaving is that you have to put a mistake in there, it must be done because only the creator is perfect. We’re not perfect, so we don’t make a perfect rug.” The weavers purposefully insert an error in their weavings because perfection is not theirs to make. Seamlessness is not human, it has no hands. The maker is in the seams, when the thread leaves, the error is introduced, and the hand remains.

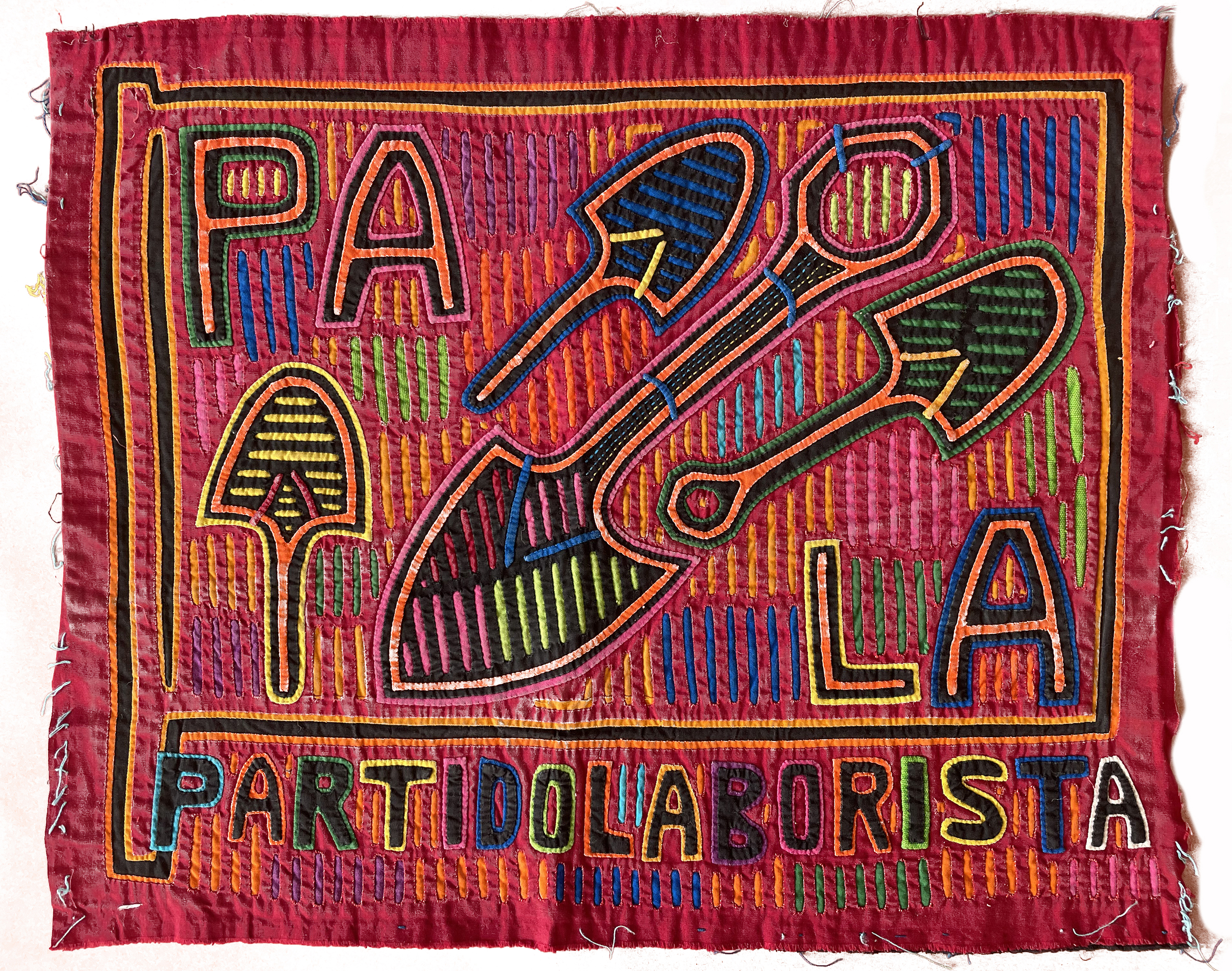

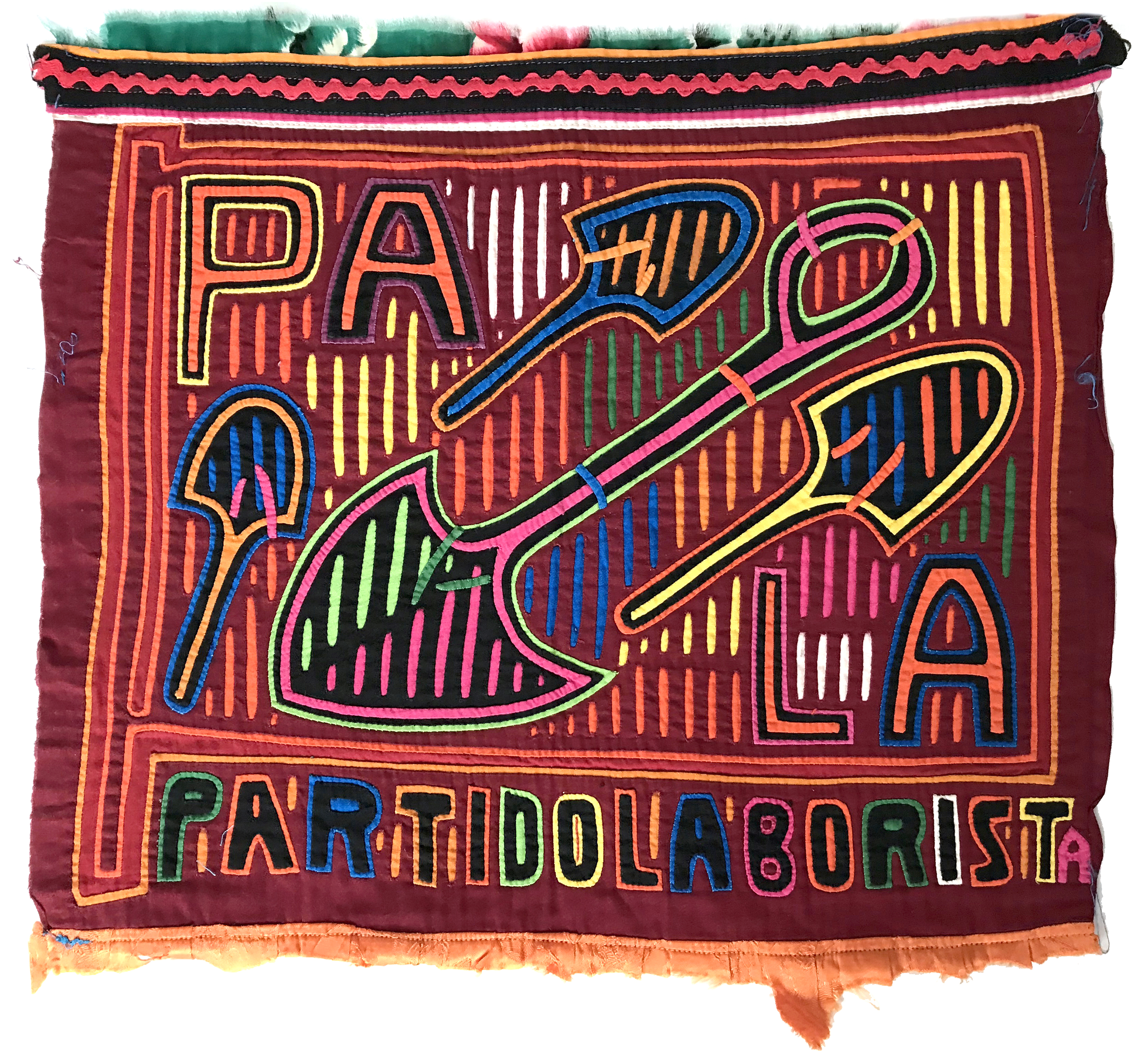

Partido laborista molas, courtesy of the author.

The more I have learned about textile-making and its complexities, the more I have wanted to view the molas closely, in person. During my visit to Santa Fe, I found a world market selling textile pieces from a great diversity of origins. I immediately looked for molas. I bought a pair of them that are, to my mind, the most appropriate flags against seamlessness.

I was attracted to these pieces out of several others that conveyed animal motifs and geometrical figures, feeling great intrigue and attraction by their forcefulness of the image and the letters. In the top section these two molas include the letters PALA, which spell “spade” in Spanish, along with the silhouette of said tool, and in the bottom section include the words “Partido Laborista” which translates to English as “Labor Party”. At the moment I did not know what party in particular was being advertised by the objects, but I read them as entities of condensed labor, with the theme present in a circular way, as it usually is in pieces of conceptual art. These two molas were saying labor with labor.

I later discovered that these two molas were made at some point in the 1960’s to promote a political entity in Panamá, the Partido Laborista Agrario. I still see them as objects that speak to the fight for dignity and rights, and about labor at large. Together these objects fight against mechanical reproduction. They speak for seamfullness and difference. Together they have a sense of homogeneity, paradoxically paired with extreme singularity. Labor is present both explicitly and implicitly, it is labor speaking for the dignity of labor itself. Because textiles are inextricably intertwined with the work required to make them.

In the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution brought a shift into the making of textiles, where automatizing fabrication implied the possibility of seamless similarity in meters and meters of woven materials. The labor was relocated, erased from the surface, which was quick to forget its material origin and always exists in a present tense. Today, most of the textiles we interact with have been technically forced to forget their history, they do not reveal themselves to us through their seams.

I was attracted to these pieces out of several others that conveyed animal motifs and geometrical figures, feeling great intrigue and attraction by their forcefulness of the image and the letters. In the top section these two molas include the letters PALA, which spell “spade” in Spanish, along with the silhouette of said tool, and in the bottom section include the words “Partido Laborista” which translates to English as “Labor Party”. At the moment I did not know what party in particular was being advertised by the objects, but I read them as entities of condensed labor, with the theme present in a circular way, as it usually is in pieces of conceptual art. These two molas were saying labor with labor.

I later discovered that these two molas were made at some point in the 1960’s to promote a political entity in Panamá, the Partido Laborista Agrario. I still see them as objects that speak to the fight for dignity and rights, and about labor at large. Together these objects fight against mechanical reproduction. They speak for seamfullness and difference. Together they have a sense of homogeneity, paradoxically paired with extreme singularity. Labor is present both explicitly and implicitly, it is labor speaking for the dignity of labor itself. Because textiles are inextricably intertwined with the work required to make them.

In the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution brought a shift into the making of textiles, where automatizing fabrication implied the possibility of seamless similarity in meters and meters of woven materials. The labor was relocated, erased from the surface, which was quick to forget its material origin and always exists in a present tense. Today, most of the textiles we interact with have been technically forced to forget their history, they do not reveal themselves to us through their seams.

We can look into the age-old history of craft associated with textiles, that continuous space of resistance, it is there, in the seams, that labor continues to fight for visibility.

Example of string quilt. Carol M. Highsmith, Hand of a quilter from Gee's Bend Alabama. The George F. Landegger Collection of Alabama Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Public domain

Some textiles are more evident bearers of seams; quilts, in particular, are a collection of them. String quilts are made of selvages, remainders of fabric, and cut-out odd shapes. The seam becomes a form that allows for these disparate pieces to meet, gather, and become an entity. Leftover shapes come together as a whole. Imprecision resides within the seams, but it is this imprecision in particular that makes a new object possible out of scraps: a future.

Seamless is a very difficult word to translate from English into other languages. Something that is seamless is continuous; it does not show its junctures, its witnesses have disappeared and it has become a homogenous surface. A seam is a moment of contact, a coming together of two different pieces of fabric. It is an encounter–a before and an after. Something that is seamless does not show this, as it has no transitions, interruptions, or indications of disparity. A seamless object/cloth/textile has no memory, and it lives in a continuous present. Seamlessness implies perfection, flawlessness. Seamlessness forgets. It is in the seams that the memory of the object resides: they allow for an opening, for a conversation to start.

1. https://www.nativetimes.com/archives/22/1217-navajo-weaver-shares-story-with-authentic-rugs