Work

About

Work

Equals

Work

By Amy DiPlacido

The American workforce arguably experienced the most rapid change of the entire 21st century within the last year, due to the Covid-19 Pandemic.

Employees left their stations on March 16, 2020, many of them not returning for the greater part of the year. Some workers have not returned at all after 20 months and counting. Americans experienced mass layoffs, furloughs, labor injustices, and record unemployment with no current signs of a full recovery. America has since grappled with inequities surrounding its workforce: the luxury of safely working from the comforts of home, contrasting with front line workers who risk their personal health and safety. Workers who were fortunate enough to keep their jobs are advocating for work from home as a new normal, prompting thought and discussion of what work looks like in 2021, and how the future of employment will evolve in the coming years.

For many people, their careers and work ethic are deeply intertwined with ideas of identity.

San Jose-based artist Ryan Carrington’s practice often references the philosophies of his family upbringing: if one is true to their work, true to others, and true to oneself, then true greatness is attainable. In the last decade, Carrington has created large-scale installations of fiber art and multimedia works inspired by American industry with a focus on how the country spends its work and leisure time. Juxtaposing tools and materials of white and blue collar workers, Carrington prompts questions about how our country values labor and class divisions, and how workers strive for the American Dream.

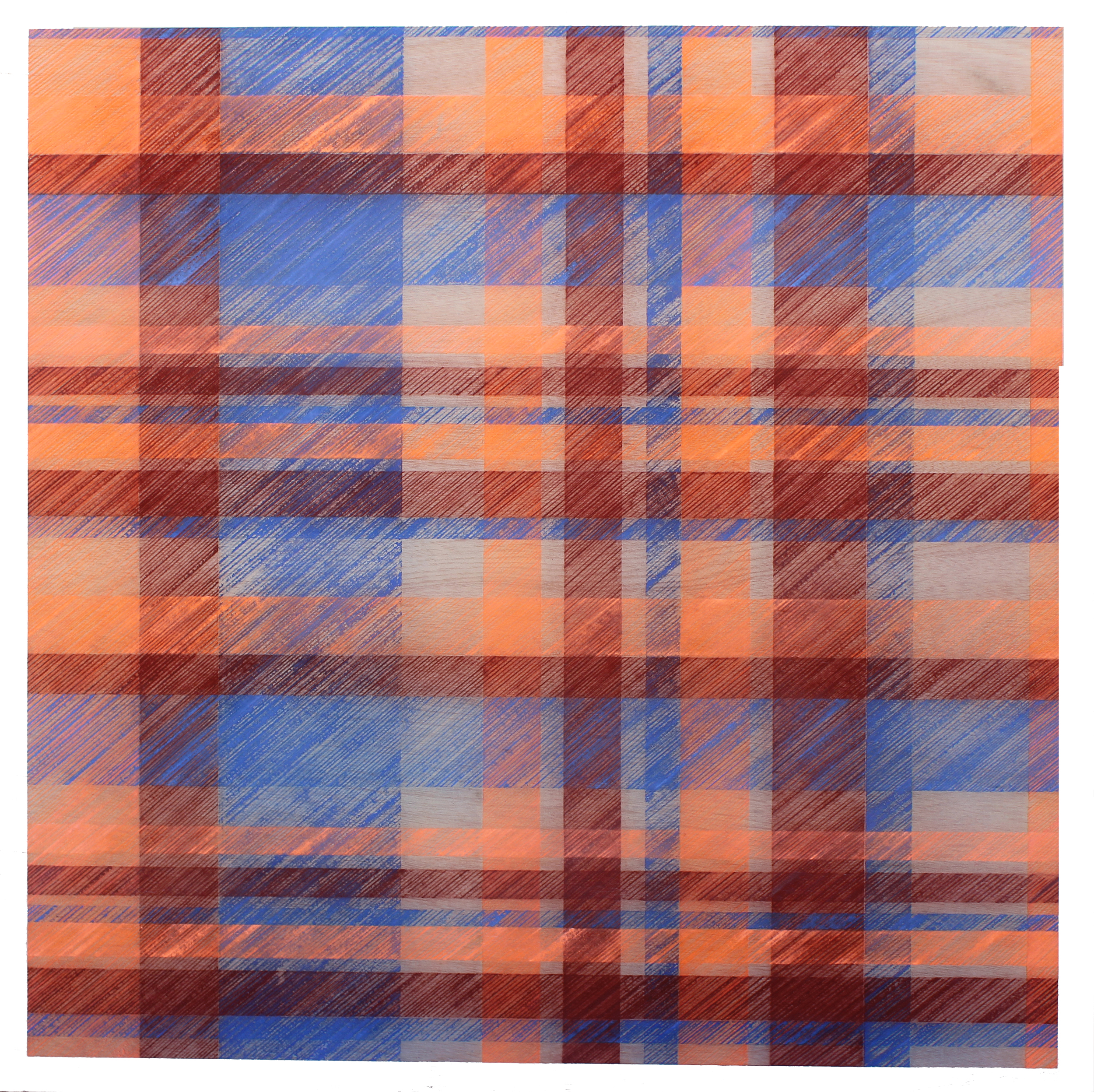

Fig.1 Chalk Line Drawing #13, 2013. Carpenter’s Chalk, U.V. Archival Finish, Plywood . (48 x 48 x .5”)

Although Carrington has a propensity for working with his hands, his Chalk Line Drawing Series rejects the artist’s hand in line making, and instead creates plaid compositions through repetition and labor using a tool found at hardware stores. The Chalk Line Drawing Series recalls the gingham seen in Americana textiles such as picnic tablecloth, plaid shirts, curtains and other home decor. By masking off areas of a plywood surface, pulling the chalk line taught, and ‘snapping’ to create colored, straight lines, Carrington and a hired Artist Assistant create mesmerizing, linear designs. The labor-intensive details of the creation serve as a symbolic performance commemorating the precision and skill required in construction work. Often this series is monotone, and occasionally depicts high-end fashion brands, which directly contrast with the working-class chalk reel.

Although Carrington has a propensity for working with his hands, his Chalk Line Drawing Series rejects the artist’s hand in line making, and instead creates plaid compositions through repetition and labor using a tool found at hardware stores. The Chalk Line Drawing Series recalls the gingham seen in Americana textiles such as picnic tablecloth, plaid shirts, curtains and other home decor. By masking off areas of a plywood surface, pulling the chalk line taught, and ‘snapping’ to create colored, straight lines, Carrington and a hired Artist Assistant create mesmerizing, linear designs. The labor-intensive details of the creation serve as a symbolic performance commemorating the precision and skill required in construction work. Often this series is monotone, and occasionally depicts high-end fashion brands, which directly contrast with the working-class chalk reel.

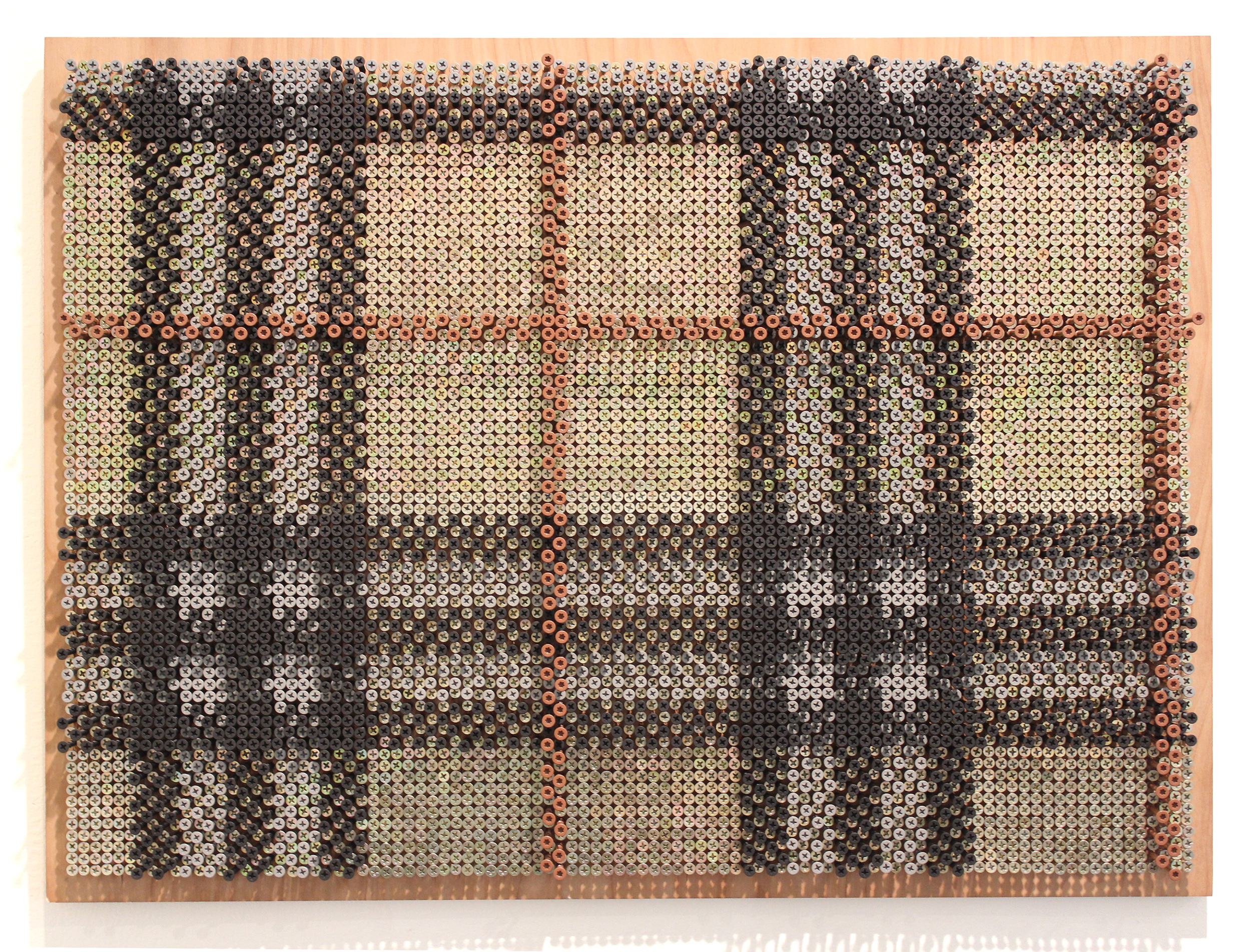

Fig. 2 Screw Relief #8; Burberry #4, 2018. Screws on Plywood (24 x 32 x 3”)

As labor and work exerted are such recurring themes in Carrington’s work, the artwork’s process cannot be too easy to create. This is how the artist justifies spending hours on tedious processes such as snapping chalk lines over time to create color fields. Perhaps no other body of work exemplifies this more than the Screw Relief Series where Carrington again performs a triumph in endurance, labor, and time. The ability to use materials and tools that are readily available from the hardware store is important to Carrington. As such, plaid patterning is assembled through screws of varying thickness, color and length to act as his mark making tool. Similar to the Chalk Line Drawing Series, and through illusion and effort, the hardware store materials transcend their humble beginnings to mimic luxury textiles. By recreating high-fashion plaids, such as Burberry and Ralph Lauren, with working class materials, Carrington provokes questions of economics, consumerism, and class hierarchies. As the Screw Relief Series involves drilling around 8000 screws into plywood, the work takes a physical toll on the artist. Ironically, the value of the Luxury Home Series and Screw Relief Series are inflated by their exclusive nature, as Carrington can only create a handful per year due to shoulder strain from repeatedly drilling screws into plywood.

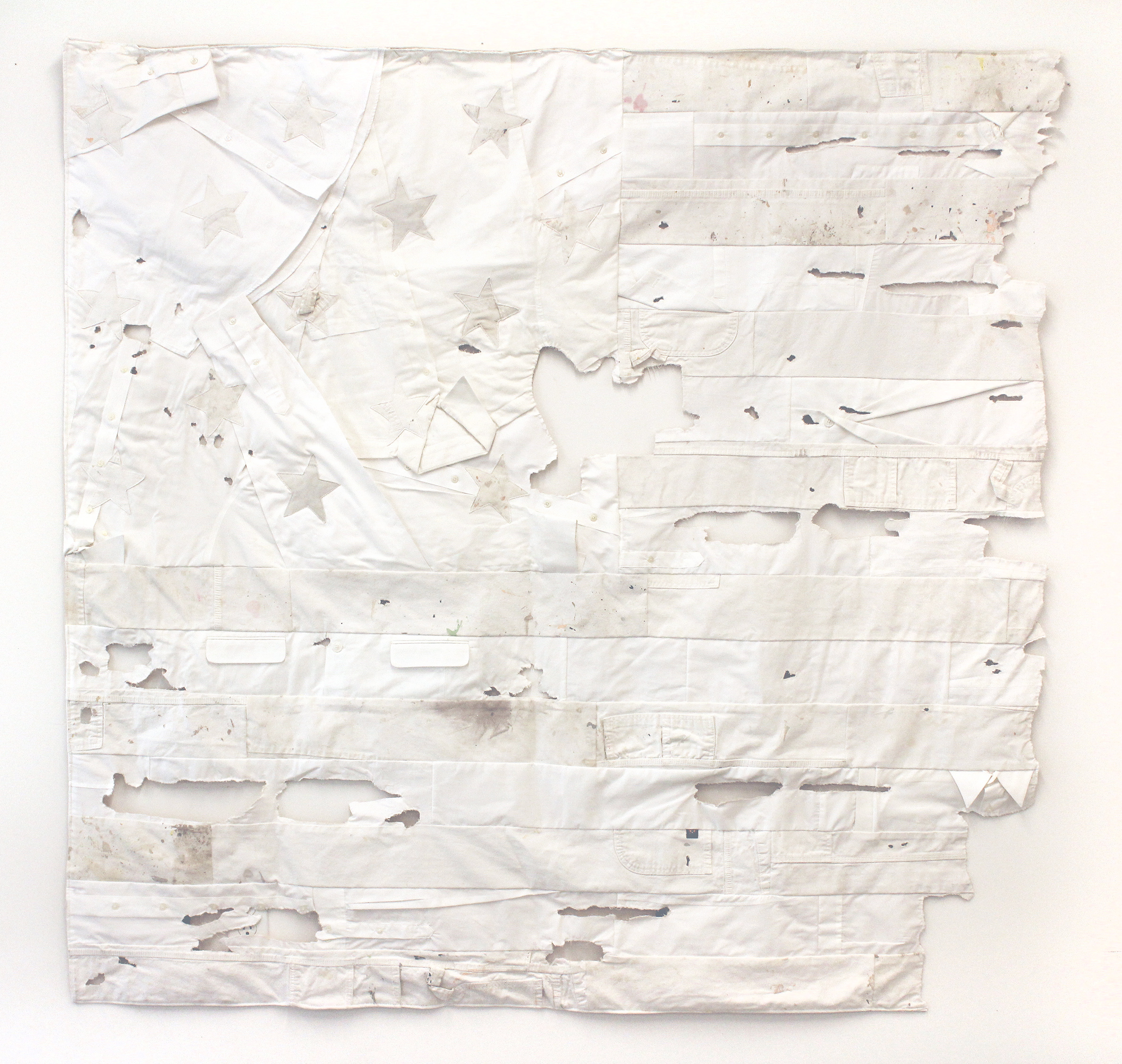

Fig. 3 Flag #19, 2020. Hospital Scrubs, Lab Coats (68 x 36”)

As a meditation on the value of labor in the United States, Carrington’s recent Flag series reproduces sewn American Flags in the same dimensions to the Congressional standard.

The garments were collected over years, asking workers to donate their clothes once discarded. Carrington then composed the flags to include a variety of careers within each arrangement: painter’s pants, jeans, Carhartt cotton duck canvas, collared shirts, suits and neckties. In these sewn assemblages, the artist highlights irregularities in his surface material, such as paint splatters, pen markings and sweat under the collar. These idiosyncrasies in cloth allow the viewer to wonder about the wearers’ personalities, their histories and the labor exerted by the wearer.

Instead of employing solid fabric in the dictated colors1, Carrington stitches pre-worn garments from white and blue collar workers as a symbol of American laborers under this unifying symbol.

The garments were collected over years, asking workers to donate their clothes once discarded. Carrington then composed the flags to include a variety of careers within each arrangement: painter’s pants, jeans, Carhartt cotton duck canvas, collared shirts, suits and neckties. In these sewn assemblages, the artist highlights irregularities in his surface material, such as paint splatters, pen markings and sweat under the collar. These idiosyncrasies in cloth allow the viewer to wonder about the wearers’ personalities, their histories and the labor exerted by the wearer.

Fig. 4 Flag #20, 2020. Hospital Scrubs, Lab Coats (36 x 68”)

Fig. 4B Flag #20 (detail), 2020. Hospital Scrubs, Lab Coats (36 x 68”)

The series started a couple of years before the Covid-19 pandemic, when Carrington was given a bag of donated nurses’ scrubs and doctors’ lab coats. It was only when the shelter in place order kept Carrington working from home on his dining room table that he decided to create the Flag Series with these pre-worn uniforms. Flag #19 and Flag #20 were created solely from the dress of healthcare providers, alternating white and blue colors, leaving in defining features such as the drawstring and cording of scrubs. The finished results pay homage to the bravery of frontline workers, during a time when healthcare was pushed to the limits amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. It is Carrington’s intention that the sewn flags celebrate pride of the American workforce, conjuring camaraderie and reflection as one union, a glimmer of hope that was needed at the height of the pandemic.

Fig. 4B Flag #20 (detail), 2020. Hospital Scrubs, Lab Coats (36 x 68”)

The series started a couple of years before the Covid-19 pandemic, when Carrington was given a bag of donated nurses’ scrubs and doctors’ lab coats. It was only when the shelter in place order kept Carrington working from home on his dining room table that he decided to create the Flag Series with these pre-worn uniforms. Flag #19 and Flag #20 were created solely from the dress of healthcare providers, alternating white and blue colors, leaving in defining features such as the drawstring and cording of scrubs. The finished results pay homage to the bravery of frontline workers, during a time when healthcare was pushed to the limits amidst the Covid-19 pandemic. It is Carrington’s intention that the sewn flags celebrate pride of the American workforce, conjuring camaraderie and reflection as one union, a glimmer of hope that was needed at the height of the pandemic.

Fig. 5 Flag #5, 2015. Carpenter's Pants, Suits, Collared Shirts, and Neckties (68 x 36")

Fig. 5 Flag #5, 2015. Carpenter's Pants, Suits, Collared Shirts, and Neckties (68 x 36")Masking the labor involved in the creation of his works is a common theme for Carrington. He attributes the illusion of perfection to the lessons of his personal upbringing of working hard and true at any task that you take on: from creating artwork to cutting the lawn. To elaborate on the symbolism, Carrington creates well-crafted artworks not dissimilar from the way a custodian cleans a room; if a custodian has performed the job correctly, the people using the building the next day should not realize that they were even present the night before. Carrington imparts this philosophy into his art practice: if he works with a great level of craftsmanship and skilled labor, the viewer can more easily enjoy an unencumbered experience with the artwork.

In the Post-Pandemic labor force, where workers are deemed either essential or not, it’s hard to predict the future of the visual arts.

In Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, a theoretical pyramid outlining human motivation by the American psychologist Abraham Maslow, the arts and other aesthetic needs remain as luxury items, typically reserved for the upper class (Maslow A.H., 1943, p. 370-396).2 Yet, at the height of the pandemic, art was deemed necessary and assisted the world for its potential to offer self-reflection, calm, and even an escape. Similarly, physical laborers who require interacting with other humans (teachers, workers in hospitality, and construction, etc.) have a newly restored appreciation for their sacrifice giving renewed value to blue and pink collared workers.

The emphasis on the hierarchies of labor in Carrington’s work is an apt reminder that indeed, the pandemic exposed deep inequities in how the country values labor, time, and physical work, but there is promise in deciding how America returns to work.

1. The American Flag’s original colors were hand dyed with Indigo plant to achieve blue and Madder Root to achieve red. The exact shades of blue and red are numbers 80075 and 80180 in the Standard Color Card of America published by the Color Association of the United States. In the Pantone system the colors are: Blue PMS 282 and Red PMS 193. The RGB numbers are: #002868 (blue) and #BF0A30 (red). (legion.org)

2. Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fh0054346

The emphasis on the hierarchies of labor in Carrington’s work is an apt reminder that indeed, the pandemic exposed deep inequities in how the country values labor, time, and physical work, but there is promise in deciding how America returns to work.

1. The American Flag’s original colors were hand dyed with Indigo plant to achieve blue and Madder Root to achieve red. The exact shades of blue and red are numbers 80075 and 80180 in the Standard Color Card of America published by the Color Association of the United States. In the Pantone system the colors are: Blue PMS 282 and Red PMS 193. The RGB numbers are: #002868 (blue) and #BF0A30 (red). (legion.org)

2. Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fh0054346

Amy DiPlacido is a visual artist and curator based in Northern California. She has held the position of Curator of Exhibitions at San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles since 2016, where she has organized numerous contemporary textile exhibitions and programs. Amy serves on the Board of Directors of the Friends of the Ixchel Museum where she co-presented Mayan Traje: A Tradition In Transition in 2019.

In her personal work she has been awarded artist residencies and participated in group and solo exhibitions throughout the United States. She received an M.F.A. in Fiber from Cranbrook Academy of Art and a B.F.A. in Fiber from Massachusetts College of Art and Design.www.ryancarringtonart.com

In her personal work she has been awarded artist residencies and participated in group and solo exhibitions throughout the United States. She received an M.F.A. in Fiber from Cranbrook Academy of Art and a B.F.A. in Fiber from Massachusetts College of Art and Design.www.ryancarringtonart.com