Throughout the twentieth century, the literary and visual world was marked by works absurdist in nature. A similar philosophy and situational condition tethered works from many different art movements together. Deviations of the Theater of the Absurd, a genre established by Martin Esslin, grew out of existentialism in the 1950s and 1960s and primarily included plays and literature. Works by authors like Samuel Beckett and Albert Camus culminated with the articulation of a philosophy in Stanford M. Lyman and Marvin B. Scott's A Sociology of the Absurd (1970). Yet, no formal "Absurdist" movement was ever specifically defined or established.

Artworks are often described as "absurd,"

but they are not canonized as "Absurd."

The absurdist impulse originated as an existential response to the trauma of the first world war. Western culture’s obsession with logic and rationalism made permissible the most irrational of behaviors and ideologies. The philosophical quandaries stemming from this era amounted to a movement towards a philosophy of absurdism, an elucidation of the lingering feelings of meaninglessness (resulting from two gruesome wars) and interest in the structures of consciousness. Most importantly, it represents a movement to reject the philosophies of enlightenment that aim to provide an overarching narrative and singular knowledge of humankind.1

Absurdist philosophy is often conflated with nihilism. While there are nihilistic tendencies in absurdist works, there is also an insistence on forcing the viewer to confront the uncomfortable. The motivation is not to shock the viewer, but to encourage empathy, or at least a small sense of familiarity with the unloved, unseen, or unwanted. This faction of modernism was born on the backs of the social conditions of the time. Marked as much by social unrest as disenchantment, the post-war decades brought movements for racial civil rights, feminism, marxism, free speach, gay liberation, and the environment. From this, a proliferation of artworks came about with a commitment to nonsense, incongruity, and a connection to the abject.

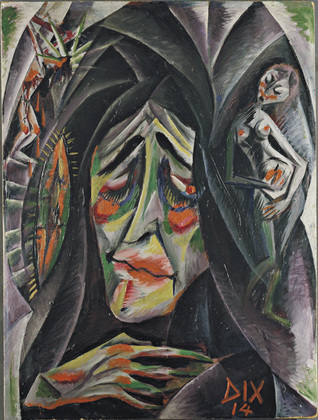

Post-war social theorists like Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, and Michel Foucault took particular interest in the radical potential of mental illness, seeing madness as a form of total rejection to enlightenment ideals. This proposition had already been politicized by Fascists decades before, when the Nazi party designated modernism as a form of mental illness and then illustrated their claim with the Degenerate Art exhibition. Many of the works included in the exhibition were done by German Expressionists like Otto Dix, who painted both external, physical realities of war, but also represented the internal toll on the psyche, and the existential torture. Post-war interest in figurative representations of internal conflict and existentialism endured as seen in the terror expressed by Francis Bacon’s popes and the alienation of Alberto Giacometti’s thin figures.

Absurdist philosophy is often conflated with nihilism. While there are nihilistic tendencies in absurdist works, there is also an insistence on forcing the viewer to confront the uncomfortable. The motivation is not to shock the viewer, but to encourage empathy, or at least a small sense of familiarity with the unloved, unseen, or unwanted. This faction of modernism was born on the backs of the social conditions of the time. Marked as much by social unrest as disenchantment, the post-war decades brought movements for racial civil rights, feminism, marxism, free speach, gay liberation, and the environment. From this, a proliferation of artworks came about with a commitment to nonsense, incongruity, and a connection to the abject.

Post-war social theorists like Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, and Michel Foucault took particular interest in the radical potential of mental illness, seeing madness as a form of total rejection to enlightenment ideals. This proposition had already been politicized by Fascists decades before, when the Nazi party designated modernism as a form of mental illness and then illustrated their claim with the Degenerate Art exhibition. Many of the works included in the exhibition were done by German Expressionists like Otto Dix, who painted both external, physical realities of war, but also represented the internal toll on the psyche, and the existential torture. Post-war interest in figurative representations of internal conflict and existentialism endured as seen in the terror expressed by Francis Bacon’s popes and the alienation of Alberto Giacometti’s thin figures.

Left: Otto Dix, The Nun, 1914, oil on cardboard

Right: Francis Bacon, Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1953, oil on canvas

Those philosophies continued to inform artworks throughout the twentieth century. In the same decades that existentialist philosophers like Camus and Søren Kierkegaard were getting tangled up in absurdist thought, a new art movement was established with an inclination toward the nonsensical: Dada. Dada changed everything. It originated in response to a spreading conservatism in the avant-garde, but also invited members of those movements to contribute.

The movement grew out of existentialist philosophy, Italian Futurism, and expressionism, but established clear boundaries between Dada and those other genres. Early Dada artists rejected German Expressionism as too universalizing of subjective experience and for its aims to insert spirituality into the avant-garde. While Italian Futurism shared Dada’s love of nonsense, it also loved fascism. One of its leading artists and a contributor to Dada exhibitions, Tommaso Marinetti, would later become Mussolini’s cultural advisor.2

The first iteration of Dada took place in 1916 in neutral Switzerland. World War I was persisting when a group of radical dissenters from across Europe first gathered at the Cabaret Voltaire, the nightclub that housed early exhibitions and performances by artists like Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, and performer Emmy Hennings. Those Dada artists were interested in the poetics of chance and the aesthetics of the avant-garde. They saw nonsense as a political position; an opposition to logic was anarchistic in the face of a growing normative conservatism that was sweeping wartime Europe.

Four years later the first Dada Fair was held in Berlin. This marked the start of a new faction of Dada, Berlin Dada. Where the first iteration saw the political in the avant-garde, this new faction sought to absolutely politicize the avant-garde. The setting in Berlin was far from that of neutral Zurich. Post World War I Germany was in the middle of a revolution that led to the abolition of the German monarchy. As were the earlier formations, its members were leftist and many were also members of the Communist Party. They embraced photomontage for its subversion of bourgeois mass media messages and for its ability to negate hierarchy or narrative through fragmentation and a mix of cultural references. The new formations parodied the original content, inserting absurdist meanings while addressing current social and political concerns, basic principles of Dada.3 One of the pioneers of photomontage was Dada artist Hannah Hoch. Many of Hoch’s photomontages depicted gender issues and modern women in Germany.

Hannah Höch, Da-Dandy, 1919, collage

French Dada daddy Marcel Duchamp

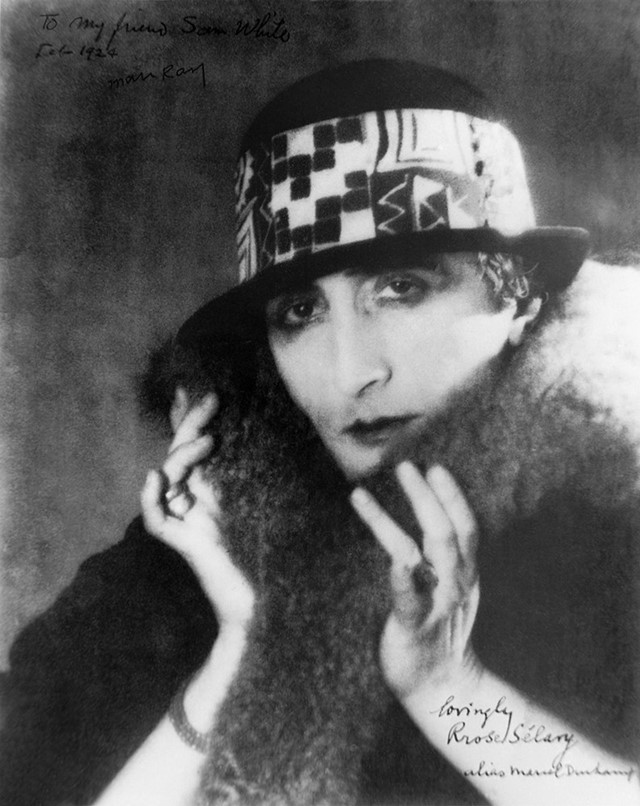

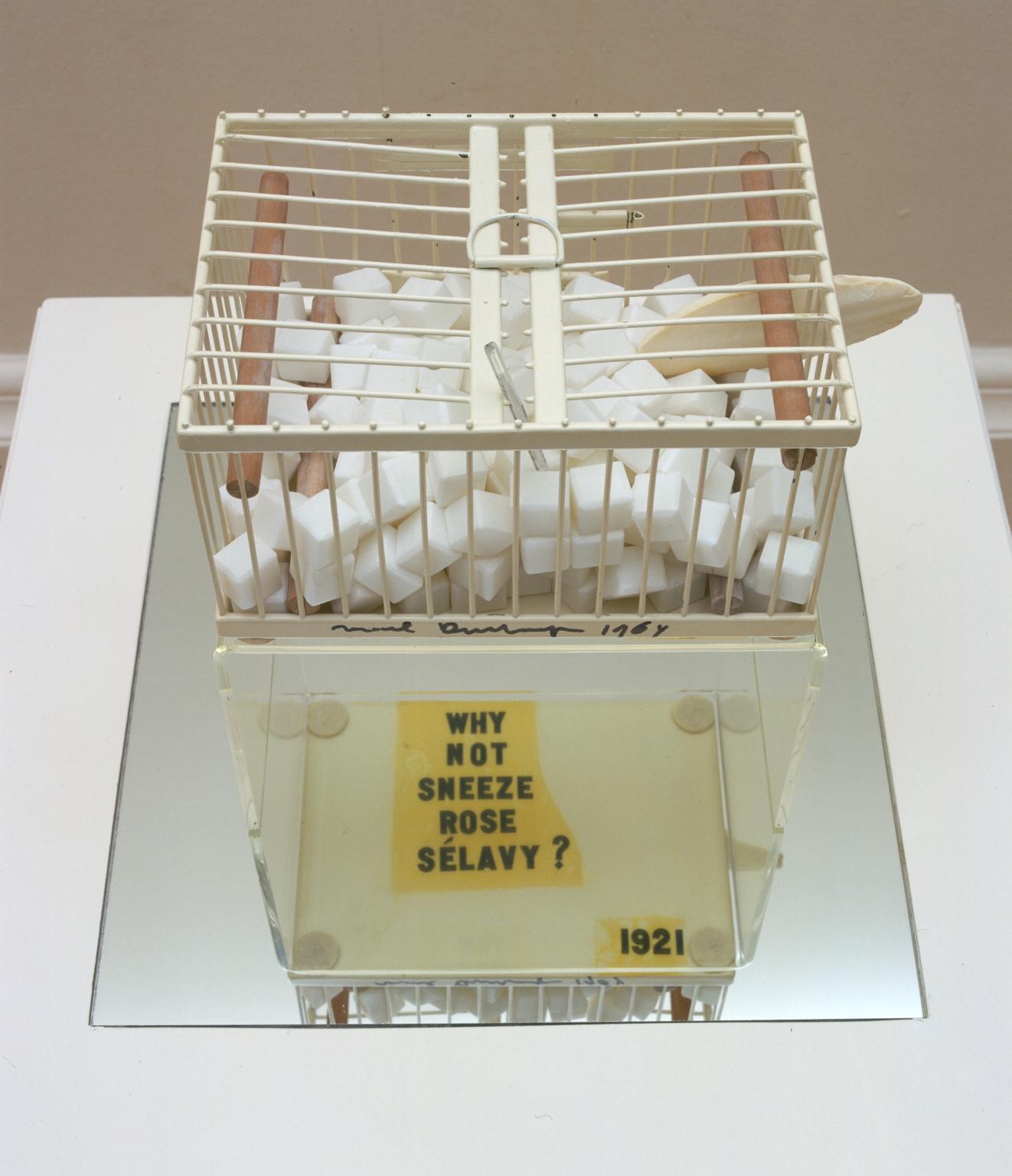

French Dada daddy Marcel Ducham’s Readymades, and Assisted Readymades, demonstrate an existential propensity and a rejection of normative values, instead elevating the abject, as in Fountain (1917). Around 1920, Duchamp invented a female alter ego, Rose Sélavy. Her full name is the phonetic spelling of the french saying, ‘eros, c’est la vie,’ translated as ‘physical love is life,’ and her last name alone translated, ‘that’s life,’ as in a casual response to minor tragedy. As Sélavy, Duchamp rejected heteronormativity and created a doubling effect in his personhood, an indexical splitting. Sélavy’s business card employs her as a Precision Oculist, playing on ‘precision optics’ as the ability to allude through perceptions, and in particular, to the role of photography as it enabled and birthed her.4 She authored a series of nonsensical inventions that frequently employed this play on vision and optics. The Assisted Readymade, Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? consists of a small cage painted white and filled with marble cubes, a thermometer, and a cuttlebone. The cuttlebone suggests that the cage is designed to house a bird. The cubes might be a deconstructed sculpture of a bird now housed in this cage. Is Rose Sélavy the bird? Duchamp had a penchant for puzzling names, frequently of indexical meaning (remember that fountain?). Duchamp explained that the thermometer is meant to test the temperature of the marble cubes, since it is the cold that causes sneezes, as absurdist an explanation as the work itself.5

Top: Man Ray, Rose Sélavy, 1921, photograph of Marcel Duchamp as Rose Sélavy

Middle and Bottom: Marcel Duchamp, Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? 1921, replica 1964, Tate

Middle and Bottom: Marcel Duchamp, Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? 1921, replica 1964, Tate

From the parentage of Dada grew many generations and iterations of absurdists whose subjects and forms transformed with the world around them. Pop artist Claes Oldenburg’s works in the 1960s processed and expelled the subjective experience of places and stuff (consumer objects) through soft, scrunchy, abject, and frequently decomposable artworks.6 In response to the march of progress overtaking New York City in the 1960s, Oldenburg depicts all that was becoming endangered at the time. In March 1960 he installed the exhibition The Street at the Judson Gallery in the Judson Memorial Church. The Street consisted of a loose recreation of the surrounding urban space made from the refuse of that space: cardboard, burlap, and newspaper. Oldenburg staged the happening Snapshots from the City inside the exhibition. Pantsless and covered with even more detritus, he writhed and squirmed and screamed and howled in anguish. The performance was ordained by his partner Pat Muschinski, dancing in scooping motions while dressed in a birdlike mask and more garbage. The scene reads like a ritual, performed insanity as a cure for the orderly.7

![]() Claes Oldenburg with Patty Mucha, Snapshots from the City, 1960, performance

Claes Oldenburg with Patty Mucha, Snapshots from the City, 1960, performance

Sharing a frequent pop art concern for elevating overlooked objects, Oldenburg created replicas of objects from the everyday life around him. In 1961 he opened The Store, an experimental art project and space that housed artworks and happenings. The Store was filled with floppy and flacid interpretations of the objects found in the nearby ‘dime stores’ that sold cheap and used items. Oldenburg’s replicas were made from plaster soaked cloth and clumsily painted. They were tactile and often grotesque. Some were huge in proportion to their namesake and the price for purchase ranged absurdly from twenty-five dollars to over eight hundred.8

![]()

Claes Oldenburg in The Store, 1961

Claes Oldenburg with Patty Mucha, Snapshots from the City, 1960, performance

Claes Oldenburg with Patty Mucha, Snapshots from the City, 1960, performance

Claes Oldenburg in The Store, 1961

In the 1980s and until his death in 2012, Mike Kelley introduced a form of absurdism in visual art that used extreme vulnerability as a new form of the abject.9

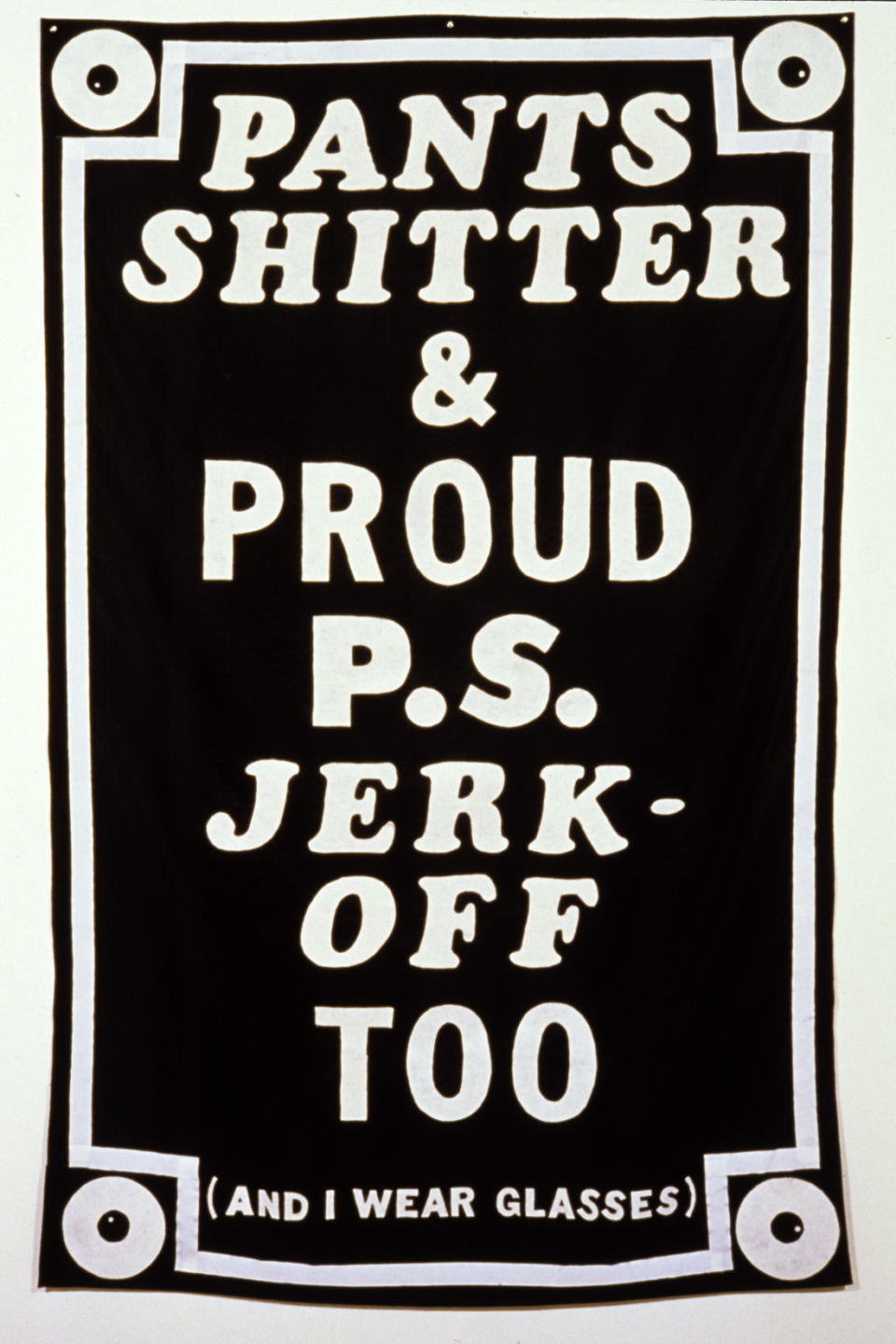

Mike Kelley, Three Point Program/ Four Eyes, 1987

He combined humor and humanism to a self deprecating end that simultaneously insisted on taking up space without conforming to politeness or social ease. He had a taste for the distasteful but not in the painful way of Oldenburg’s performances. Kelley’s works embraced the loser in everyone. In his 1987 banner, Three Point Program/ Four Eyes, Kelley celebrates the broken body, loudly. The floor to ceiling length banner reads, “PANTS SHITTER AND PROUD P.S. JERK-OFF TOO (AND I WEAR GLASSES).” He posits this as a political stance, sewing it in a black and white palette with decorative framing in a nod to suffragette banners. Its vulnerability falls short of shocking. But it is also not pathetic. It’s too well made for pity. Similarly sized, Daddy, from the same year, offers another shout out to the lesser man. The banner depicts a large floating eye, well, not quite floating, as it’s bound to two posts that border it. The eye is almost reminiscent of Sauron, the all seeing evil eye from Lord of the Rings (bad daddy), but positioned sideways. The posts that border it on either side are shielding another set of posts, and from these pairs the eye is being stretched, like on a reconfigured medieval torture rack. Or is it a new form of spa treatment? On a deep eggplant background, and against a richly hued red setting sun, the banner could be an advertisement for a new cult of exercise aimed at men who wish they were more masculine. The daddy of Daddy is an all seeing raw nerve with an identity crisis. Both banners offer a familiar, homey, and even feel good aesthetic, but with an acne faced, potentially a bit bullied, and fecal obsessed message.

Top: Mike Kelley, Three Projects installation view, The Renaissance Society, 1988

Bottom: Mike Kelley, Three Projects installation view with Daddy, 1987, on the left, The Renaissance Society, 1988

Bottom: Mike Kelley, Three Projects installation view with Daddy, 1987, on the left, The Renaissance Society, 1988

Since the 1990s, absurdism has been used as a tactic to resee and reframe history, politics, and culture, in a language of humor and levity that brings pleasure to the painful process of looking.

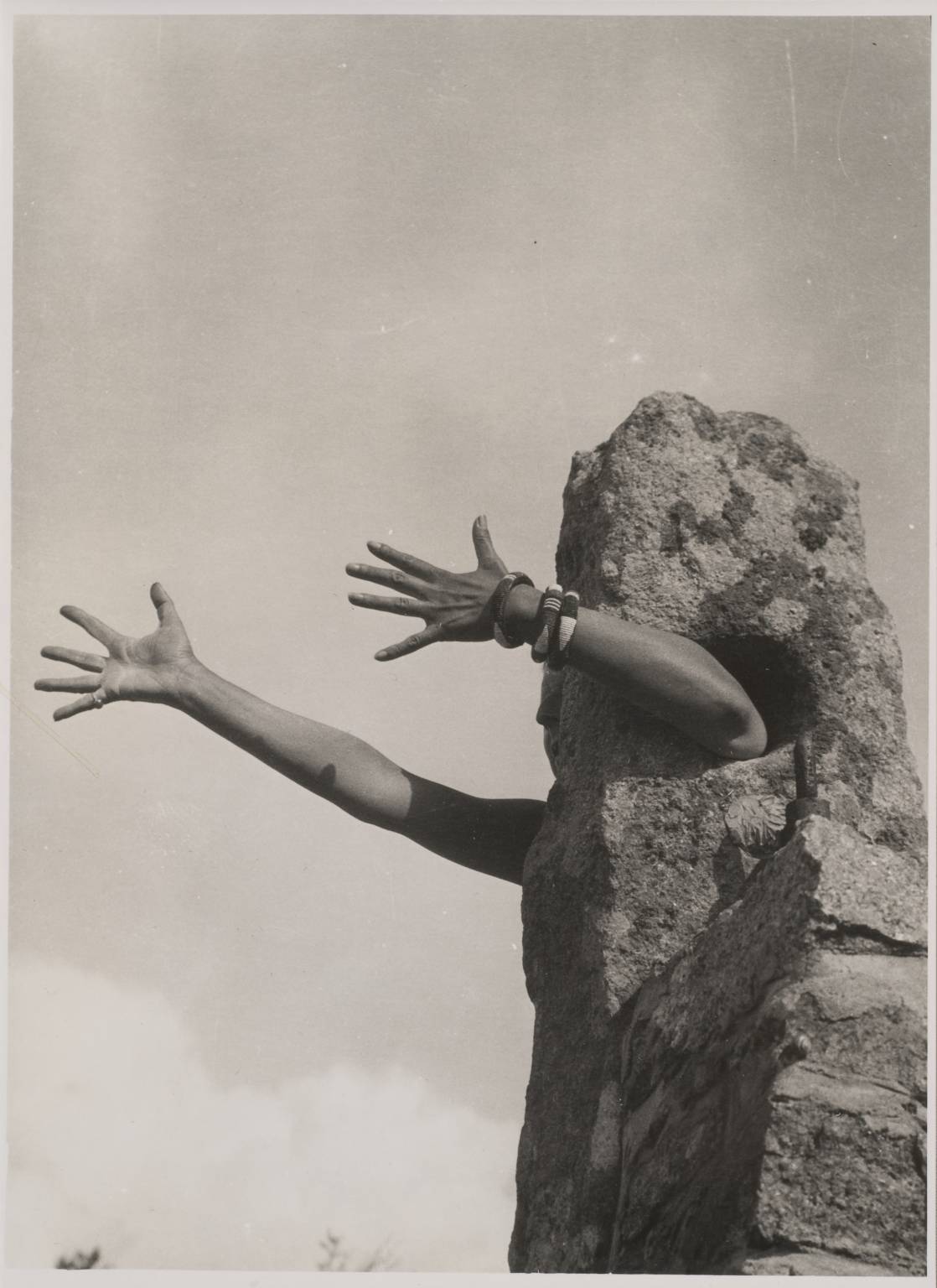

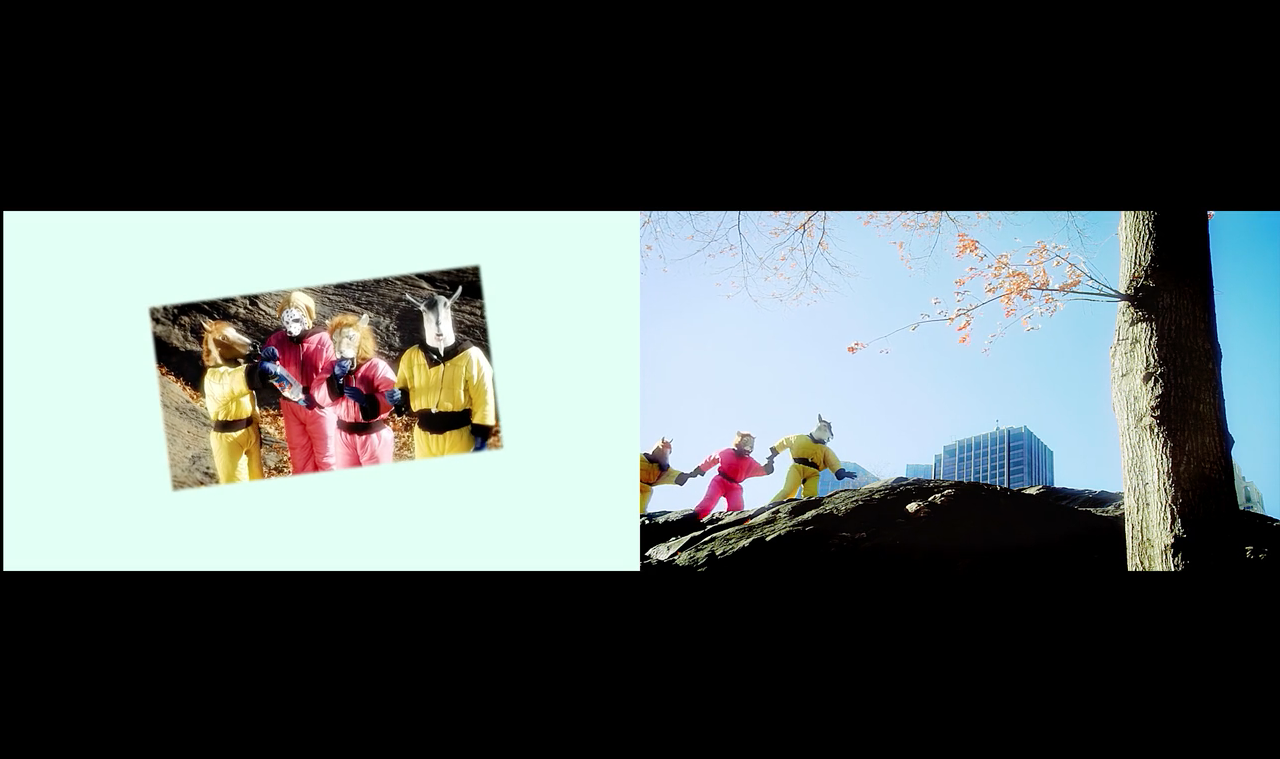

In Lenore Malen’s 2017 3-channel video installation, The Reason of the Strongest is Always the Best, we are introduced to four figures dressed in yellow or pink hazmat body suits, with the heads of animals: a horse, a lion, a goat, and what might be a dalmation, respectively. 10 The creatures are struggling to explore a large rock landscape. The scene conjures the image of gender fluid surrealist Claude Cahun’s large gesturing admonishment as a rock in I Extend My Arms (1931/32), and with it inserts the critique of gender roles and gives a formal indication of the expansion of perceived reality. The difficulty of the animals’ movements suggest that this level of gravity is foreign to them. From there we can deduce that we are witnessing four visitors from another planet. As they survey the terrain that they have stumbled upon, we watch their examination with bated breath; what is their goal? Are they searching for a lost comrade? Are they collecting samples to take back for further research? We do not see any such activities. Their movements are almost slapstick, but lack even the accidents or physical violence of the comedic genre. The endless journey with no goal in sight conjures the nonsensical plot lines of the Theatre of the Absurd.11

Claude Cahun, I Extend My Arms, 1931-1932

Introductory credits to the video installment name Malen’s references for the work. She names a fable of Jean de La Fontaine, who seems, in many ways, Beckett’s opposite12 insomuch as Beckett rejected balance, the idea of being “natural,” and occasionally refused even punctuation.13 In this sense, Malen superimposes an illogical filter onto a French classic. Is this the story between the story; our protagonists between life lesson worthy events? Like Vladimir and Estragon, Malen’s characters too lack chance for arrival or purpose.

As Malen tells us, the non-fictional landscape that our explorers occupy is Umpire Rock, an ancient schist formed by subterranean heat and pressure from the earth’s interior, during the Paleozoic era, and located in Central Park. This is the stage of the play, a natural and ancient landscape. The stage background reveals a stark contrast to the stage, a city of massive buildings, and a sign of endless progress. The ‘difference’ of the explorers is the denoted message, but the violence of progress is the connoted message. As they discover a bag of Ruffles chips in the ancient landscape, the absurdity of the scene shifts from their forms to the juxtapositions of everyday life on earth, in a capitalist Western culture. This message is reinforced by text offered in the video, located more as narratorial interjection than subtext, “That innocence is not a shield, a story teaches not the longest. The strongest reasons always yield to the reason of the strongest.”14 The poem alludes to imperialism and enlightenment. In “reason yielding to strength,” we find the horrors of facism and imperialism from which early absurdism was born in response. “The strong reason yielding to the reason of the strongest,” also refers to the untangleable relationship of illogic tied to the attempt for ultimate logic that was the motivation for reductive Enlightenment theories, and an excuse for facism.

As Malen tells us, the non-fictional landscape that our explorers occupy is Umpire Rock, an ancient schist formed by subterranean heat and pressure from the earth’s interior, during the Paleozoic era, and located in Central Park. This is the stage of the play, a natural and ancient landscape. The stage background reveals a stark contrast to the stage, a city of massive buildings, and a sign of endless progress. The ‘difference’ of the explorers is the denoted message, but the violence of progress is the connoted message. As they discover a bag of Ruffles chips in the ancient landscape, the absurdity of the scene shifts from their forms to the juxtapositions of everyday life on earth, in a capitalist Western culture. This message is reinforced by text offered in the video, located more as narratorial interjection than subtext, “That innocence is not a shield, a story teaches not the longest. The strongest reasons always yield to the reason of the strongest.”14 The poem alludes to imperialism and enlightenment. In “reason yielding to strength,” we find the horrors of facism and imperialism from which early absurdism was born in response. “The strong reason yielding to the reason of the strongest,” also refers to the untangleable relationship of illogic tied to the attempt for ultimate logic that was the motivation for reductive Enlightenment theories, and an excuse for facism.

Screenshots from Lenore Malen, The Reason of the Strongest is Always the Best, 2017, 3-channel video

Working concurrently to Malen, Jeffrey Gibson’s works too are absurd. They reject and subvert the confines of logic that reduce a culture to a fixed image.15 The forms embed metaphors onto functional objects whose use would immediately negate the metaphor. Birds of a Feather (2017) presents the viewer with an unwearable dress in the form of a beaded bodysuit with gem colored tassels for arms, shin guards made of bells, and a graphic op-art enclosed beaded face. The metaphor is even more visible in Manifest Destiny (2016), a stud, bead, and tassel covered large stuffed cylinder that compares native life to a punching bag, but has a plan of defense in store–please punch this bag, you will hurt more. In both works, Gibson embeds the objects with signs of a new queer indigenous genre, overwhelming them with color, bedazzled beyond function.

Left: Jeffrey Gibson, Manifest Destiny, 2016

Right: Jeffrey Gibson, Birds of a Feather, 2017

Right: Jeffrey Gibson, Birds of a Feather, 2017

Gibson demonstrates an abhorrence of the cult of logic in One Becomes the Other (2015). The video witnesses music and dance performances set in an archival storage space. From its exhaustiveness and sterility, I hypothesize that this is the Smithsonian Museum’s storage department, or some other great institution. The room consists of shelves full of artifacts. This is our stage. While getting ready, performers pick their accessories from the displays in the galleries of the museum. The objects are not dead objects; they are things in use for a culture that still persists. This is made no more apparent than with the smallest and so easily overlooked detail of a drummer pulling his drum from a reusable cotton tote bag with a screen printed image of a medicine wheel. The mundanity of the familiar contemporary give-away, set in this antiseptic hallmark to bureaucracy, is a reminder of just how not dead the owner’s of these items really are today. In a brief cuttaway scene a white male museum staffer pushes a trolley cart of artifacts past a large painting of a river valley surrounded by mountains, much like the Sierra’s, in a reenactment of westward expansion and the philosophy of manifest destiny. The scene also alludes to the movement of these objects from one culture to another, and ultimately out of frame. As the music begins to swell, we follow the movement of the museum staffer as he swiftly walks through the maze of new construction pathways and ramps until, finally, he arrives in a large room, monopolized by a long row of movable shelves full of artifacts. Those artifacts are likely all native, indigenous, and first peoples, and essentially they are a systemized hoard of once beloved objects.

Screenshots from Jeffrey Gibson, One Becomes the Other, 2015, video

This essay is not meant to outline an art movement. Its goal might be to better understand the absurdist inclination. It could also be to point out what the works have in common and what historical details informed their creation. The artists from each generation of absurdist movements I have considered respond as social commentators from within the social and political struggles dominating their era, not outside looking in. Each work demonstrates a rejection of congruity, logic, and rationalism. They all share an intellectual anti-intellectualism compatible with Beckett and the “Theatre of the Absurd.” Like their predecessors, the works from my list question all forms of power, including knowledge, while simultaneously believing in knowledge. They are embodied critiques. Some have an anti-aesthetic aesthetic, but not all. Really there is no singular and overarching narrative of an absurdist philosophy and that is the point of its existence.

1

Stanford M. Lyman and Marvin B. Scott, A Sociology of the Absurd.

2

Benjamin H. D. Buchloh and Rosalind Krauss, “1909,” from Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, 96.

3

Rudolf Kuenzli, “Survey,” from Dada, Phaidon Press.

4

Rosalind Krauss, “1918,” from Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, 159.

5

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81966

6

Claes Oldenburg was born in Stockholm in 1929 and grew up in Chicago. He moved to New York City in 1956 and fell in with pop artists like Jim Dine, Red Grooms, and Allan Kaprow.

7

Kelly Baum, “Think Crazy,” from the exhibition catalogue Delirious: Art at the Limits of Reason 1950 / 1980s, 25-26.

8

Yve-Alain Bois, “1961,” from Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism Volume Two, 454.

9

Mike Kelley was born in Wayne, Michigan a suburb of Detroit in 1954. In 1976 he moved to California to go to graduate school at Cal Arts where he received his Masters in Fine Arts. He lived and worked in Los Angeles until his suicide in 2012.

10

Lenore Malen was born in New York City and lives and works there today. She is known for her video installations and performance art.

11

The Theatre of the Absurd is a European based genre of absurdist fiction and plays that was active in the late 1950s.

12

From descriptions of La Fontaine’s writing as “utterly correct, balanced, easy, and natural, taken for their word as I do not read French, and do not enjoy fables.

13

New World Encyclopedia entry for Jean de la Fontaine.

14

Lenore Malen, The Reason of the Strongest is Always the Best, 2017, 3-channel video.

15

Jeffrey Gibson was born in Colorado in 1972. He is a Mississippi Choctaw-Cherokee. Today he lives and works in Hudson, New York.