Fabricating Utopia

Barbershop: The Art of Queer Failure

Ace Lehner

As I fade one side of Zeke’s head and shave a hard-edged diagonal line down the other from ear to nape of the neck, we talk. They explain how they intend to have a conversation with their family about intersectional identity, and how gender and racialization are visually regulated regimes that exert pressure over our lives.

They want their family to understand at least to some extent why trans femmes of color are disproportionately subjected to pathologizing and violence.1 They tell me about how their family has finally accepted them as queer but that they are still struggling to get their biological family to come around to the fact that they use gender-neutral pronouns. We talk about this while the installation Barbershop: The Art of Queer Failure is crowded with folks watching and listening.

Our intimate moment of haircutting is also a performance. Our discussion sparks side conversations about the complexity of gender, identity, and how visual culture is an integral part of negotiating identities. Via our exchange, the other folks in the installation become part of the performance and key interlocutors. Onlookers come and go, a crowd gathers and wanes. The fluctuating community is comprised of folks ranging in age from elementary school children to the elderly, and conversations shift from someone asking “Isn’t queer a bad word?” to an eight-year-old telling me that they are not a boy or a girl. All questions and comments are addressed with respect and in a laid-back, conversational tone that the barbershop elicits. I answer the questions directed at me while focusing my attention on the person whose hair I’m cutting.

Barbershop: The Art of Queer Failure embraces the ethos of queer failure as a productive way of proposing alternatives rather than adhering to traditions of barbershops, which under the guise of giving haircuts, often reinforce notions about heteropatriarchal masculinity. The installation itself resembles a barbershop, but, rather than using the aesthetics found in a cis-normative, hetero patriachal barbershop, Barbershop: The Art of Queer Failure, which debuted at the Wassaic Project in 20192 is comprised of loud patterned textiles, images of queer icons giving haircuts, it’s robustly textured, with pompoms, tinfoil, fuzzy fabric, faux fur, sequins, and much more. Glitter curtains mark the entrance; the walls are adorned with juxtapositions of multi-colored fabric stretched over plywood and staple gunned much the same way one would stretch a canvas or upholster furniture. Strings of multi-colored pompoms appear throughout, and Andy Warhol’s factory is referenced by the use of aluminum foil on the walls. A playful mix of various queer musical outfits punctuates the air, while party lights, a disco ball, and a faux zebra rug all adorn the space to create an ambiance that is akin to a queer club coupled with a campy parlor.

The title of the project, Barbershop: The Art of Queer Failure, refers to a book by Jack Halberstam, wherein he explores queerness and its relationship to failure. Halberstam reframes dominant conceptions of failure itself and observes how in failing to succeed in the expected normative ways queers engage in a praxis of creating alternatives. In The Queer Art of Failure, Halberstam argues that in present-day capitalism, particularly in the U.S., there is an ideological conflation between optimism and material success. While failure conversely is linked to one’s shortcomings.3 Halberstam argues that in Western culture, such ubiquitous positivity and success are directly linked to the oppression and disenfranchisement of othered constituencies and that this ubiquitous optimism occludes the bigger picture of alienation and oppression. Failure becomes a necessary means of producing all sorts of alternatives. Thinking through failure in these ways opens up a framework of creating viable alternatives not invested in replicating or adhering to dominant cultural norms.

The title of the project, Barbershop: The Art of Queer Failure, refers to a book by Jack Halberstam, wherein he explores queerness and its relationship to failure. Halberstam reframes dominant conceptions of failure itself and observes how in failing to succeed in the expected normative ways queers engage in a praxis of creating alternatives. In The Queer Art of Failure, Halberstam argues that in present-day capitalism, particularly in the U.S., there is an ideological conflation between optimism and material success. While failure conversely is linked to one’s shortcomings.3 Halberstam argues that in Western culture, such ubiquitous positivity and success are directly linked to the oppression and disenfranchisement of othered constituencies and that this ubiquitous optimism occludes the bigger picture of alienation and oppression. Failure becomes a necessary means of producing all sorts of alternatives. Thinking through failure in these ways opens up a framework of creating viable alternatives not invested in replicating or adhering to dominant cultural norms.

Fresh cut courtesy of the Artist Ace Lehner

Fresh cut courtesy of the Artist Ace Lehner

Embracing the ethos of queer failure as a productive way of proposing alternatives rather than adhering to cultural norms and ideological traditions of success, the installation and social practice piece takes the barbershop motif and queers it, creating a space for queer worlding. The project intentionally fails to replicate a cis normative heteropatriarchal barbershop in aesthetics, in the cuts given, in who participates, or in even in the barbers’ abilities. I am not a trained barber; I am an interdisciplinary visual studies scholar and artist interested in exploring intersectional queer identities via creative praxis and collaboration. But I have been giving myself and my fiend's haircuts for over a decade. Nothing of this barbershop aims to perpetuate cis normative, hetero-patriarchal success. Instead, my aim with this work is to create space for queers and queer allies to gather, playfully fail to show up in normative ways, and actively rethink essentialist ideas about masculinity and binary gender aesthetics.

The impetus for the project came out of my own experience of being a non-binary trans queer person who loves getting haircuts in barbershops and as someone who has also experienced tension and hostility around masculinity policing in these environments.4 While it is enjoyable to extend my amateurish barber abilities to others via the space of an installation project, my aim with this project is to create space to ask questions about essentialist beliefs about masculinity and binary gender. Barbershops are notoriously great vehicles for all types of conversations, and the queer aesthetics and ethos of the installation facilitates celebrating queerness and gender non-conformity. It is essential to create queer space, particularly in this political climate, and when the numbers of queer spaces in the country are dwindling. This space is not meant to essentialize what queerness is -anyone is welcome to participate, observe, and hang out; in this space, queerness is porous and expansive.

![]()

For those who want to participate, haircuts are given on a first-come, first-served basis, and logged by names written on a chalkboard. All haircuts are offered in exchange for an act of queer world-making before the haircut grows out. The act given in exchange is negotiated during one’s haircut. The patron and artist have an intimate conversation about queerness and identity while onlookers watch and listen to the performance. Some queer world-making actions of previous participants are posted in the installation. These have included cis- straights allies volunteering at local LBTQ centers, and folx having difficult conversations with conservative family members about the nuances of queer identity, and the importance of critically interrogating one’s biases.

For those who want to participate, haircuts are given on a first-come, first-served basis, and logged by names written on a chalkboard. All haircuts are offered in exchange for an act of queer world-making before the haircut grows out. The act given in exchange is negotiated during one’s haircut. The patron and artist have an intimate conversation about queerness and identity while onlookers watch and listen to the performance. Some queer world-making actions of previous participants are posted in the installation. These have included cis- straights allies volunteering at local LBTQ centers, and folx having difficult conversations with conservative family members about the nuances of queer identity, and the importance of critically interrogating one’s biases.

After I finish giving the last queerly failing haircut of the day I look back at the installation, all the polaroid's I have taken of participants, the massive pile of hair on the floor, and I think about how in this ephemeral space we have made a utopian queer universe that is porous in both who identifies under the sign if queer community and where the personal and physical boundaries are drawn. My hope is that the conversations move outward as each participant creates their own acts of queer worlding before and after their haircuts grow out.

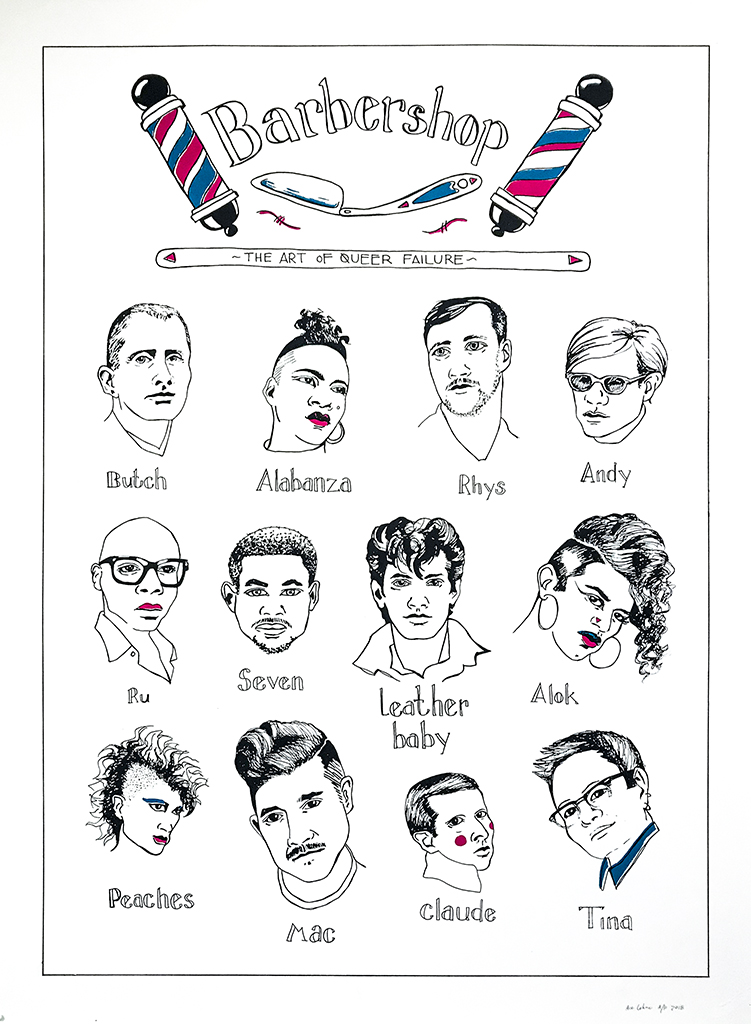

Barbershop: The Art of Queer Failure, 30” x 40” screen-print, edition of 30, 2019.

The poster is hand-drawn and screen printed in the style of iconic barbershop posters. But instead of showcasing various versions of hetero-patriarchal, cisnormative, masculinity masquerading as haircuts, this poster images queer and trans culture producers, artists, and scholars of various sexual and gender orientations that all have short, barbered hairstyles. Aiming to point out that a barbershop is ostensibly about clipper style haircuts, not about the covert maintenance of essentialist ideas about masculinity, anyone of any gender can have a clipper style haircut. The poster is for sale, and part of the proceeds go to the Transgender Law Center, and the rest goes to helping fund the continuation of the project.

After I finish giving the last queerly failing haircut of the day I look back at the installation, all the polaroid's I have taken of participants, the massive pile of hair on the floor, and I think about how in this ephemeral space we have made a utopian queer universe that is porous in both who identifies under the sign if queer community and where the personal and physical boundaries are drawn. My hope is that the conversations move outward as each participant creates their own acts of queer worlding before and after their haircuts grow out.

1 For info in violence perpetrated against trans femmes of color see the HRC website: https://www.hrc.org/resources/violence-against-the-trans-and-gender-non-conforming-community-in-2020, also see the Transgender Law Center website at: https://www.hrc.org/resources/violence-against-the-trans-and-gender-non-conforming-community-in-2020. NCTE, “Murders of Transgender People in 2020 Surpasses Total for Last Year in Just Seven Months,” in NationalCenter for Transgender Equality, August 7, 2020, https://transequali

ty.org/blog/murders-of-transgender-people-in-2020-surpasses-total-for-last-year-in-just-seven-months, Elinor Aspergen, “Transgender Murders are ‘Rampant” in 2020: Human Rights Campaign counts 21 So Far, Nearly Matching Total of a Year Ago,” in USA Today, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/07/08/trangender-murders-2020-human-rights-campaign/5395092002/.

cárdenas “Dark Shimmers,” 161-181. She discusses how heightened imaging of trans people has impacted other trans folks (170-173). Morgan Collado, “A Trans Woman of Color Responds to the Trauma of Tangerine,” Autostradle, 26 August 2015, https://www.autostraddle.com/a-trans-woman-of-color-responds-to-the-trauma-of-tangerine-301607/, (accessed December 8, 2018). Miss Major Griffin-Gracy and CeceMcDonald in Conversation with Toshio Meronick, “Cautious Living: Black Trans Women and the Politics of Documentation,” in Tourmaline, 29. McDonald points out that she herself does not readily fit the narrow prescription of what a trans femme should be and look like. For more on CeCe McDonald see: Sabrina Rubin Erdely, “The Transgender Crucible,” in Rolling Stone, July 30, 2014. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/the-transgender-crucible-114095/; Dee Lockett, “The Traumatic Reality of Getting Sent to Solitary Confinement for Being Trans That Orange Is The New Black Can’t Show” Vulture June 28, 2016. https://www.vulture.com/2016/06/cece-mcdonald-as-told-to-orange-is-the-new-black.html) accessed July 19, 2019. Also see: CecE McDonald, “I Use My love to Guide Me Through Those Fears,” in BCRW, http://bcrw.barnard.edu/fellows/cece-mcdonald/; also see: Selena Qian “Activist CeCe McDonald takes allies to task in public talk,” Chronicle, Dune University, November 11, 2017, https://www.dukechronicle.com/article/2017/ 11/171129-qian-cece-mcdonald

2 I had done a residency at the Wassaic project in 2018. See: https://www.wassaicproject.org/artists/artist-profiles/list/ace-lehner . Wassaic Summer exhibition site: https://www.wassaicproject.org/events/2019-summer-exhibition

3 J. Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

4 For examples see: Nancy Dillon, “transgender man in California haircut discrimination beef wins settlement from barbershop,” New York Daily News, August 22, 2016 https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/transgender-man-haircut-discrimination-beef-wins-settlement-article-1.2761192. Harriet Hernando, “transgender man refused haircut after being told ‘you’re female and this is a male barber’s shop,’” Mirror June 3, 2016 https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/real-life-stories/transgender-man-refused-haircut-after-8106752. Tim Loc, “Transgender Man Settles Lawsuit With Barbershop That Denied Him A Haircut,” LAist, August 19, 2016 https://laist.com/2016/08/19/transgender_man_settles_lawsuit_aft.php.

cárdenas “Dark Shimmers,” 161-181. She discusses how heightened imaging of trans people has impacted other trans folks (170-173). Morgan Collado, “A Trans Woman of Color Responds to the Trauma of Tangerine,” Autostradle, 26 August 2015, https://www.autostraddle.com/a-trans-woman-of-color-responds-to-the-trauma-of-tangerine-301607/, (accessed December 8, 2018). Miss Major Griffin-Gracy and CeceMcDonald in Conversation with Toshio Meronick, “Cautious Living: Black Trans Women and the Politics of Documentation,” in Tourmaline, 29. McDonald points out that she herself does not readily fit the narrow prescription of what a trans femme should be and look like. For more on CeCe McDonald see: Sabrina Rubin Erdely, “The Transgender Crucible,” in Rolling Stone, July 30, 2014. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/the-transgender-crucible-114095/; Dee Lockett, “The Traumatic Reality of Getting Sent to Solitary Confinement for Being Trans That Orange Is The New Black Can’t Show” Vulture June 28, 2016. https://www.vulture.com/2016/06/cece-mcdonald-as-told-to-orange-is-the-new-black.html) accessed July 19, 2019. Also see: CecE McDonald, “I Use My love to Guide Me Through Those Fears,” in BCRW, http://bcrw.barnard.edu/fellows/cece-mcdonald/; also see: Selena Qian “Activist CeCe McDonald takes allies to task in public talk,” Chronicle, Dune University, November 11, 2017, https://www.dukechronicle.com/article/2017/ 11/171129-qian-cece-mcdonald

2 I had done a residency at the Wassaic project in 2018. See: https://www.wassaicproject.org/artists/artist-profiles/list/ace-lehner . Wassaic Summer exhibition site: https://www.wassaicproject.org/events/2019-summer-exhibition

3 J. Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

4 For examples see: Nancy Dillon, “transgender man in California haircut discrimination beef wins settlement from barbershop,” New York Daily News, August 22, 2016 https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/transgender-man-haircut-discrimination-beef-wins-settlement-article-1.2761192. Harriet Hernando, “transgender man refused haircut after being told ‘you’re female and this is a male barber’s shop,’” Mirror June 3, 2016 https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/real-life-stories/transgender-man-refused-haircut-after-8106752. Tim Loc, “Transgender Man Settles Lawsuit With Barbershop That Denied Him A Haircut,” LAist, August 19, 2016 https://laist.com/2016/08/19/transgender_man_settles_lawsuit_aft.php.